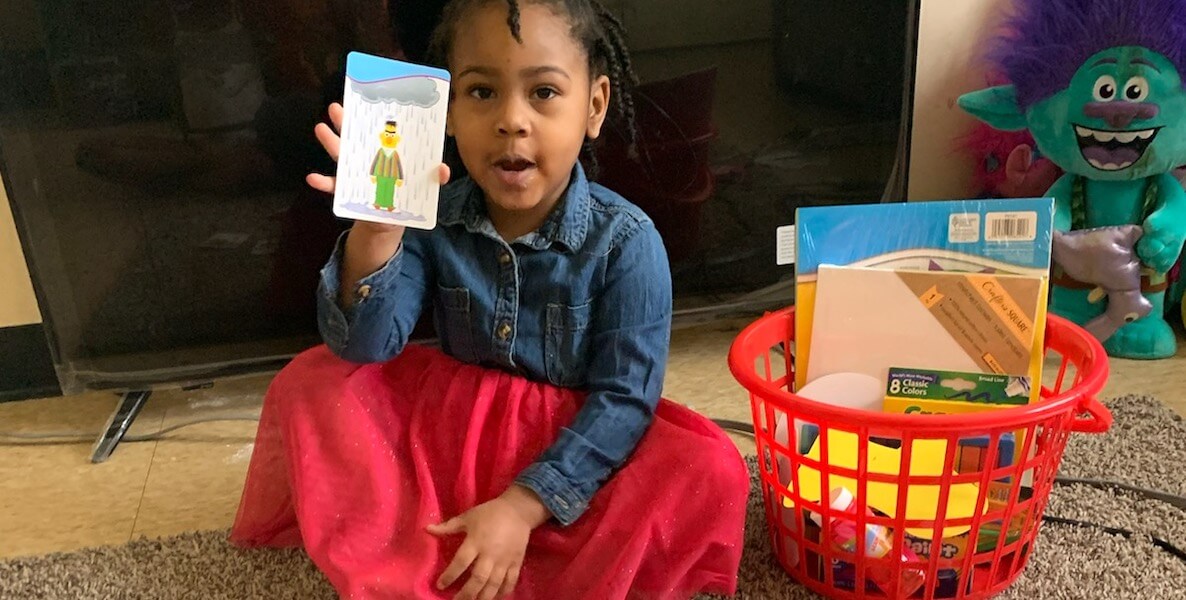

![]() I have three children in public schools in Philadelphia. After an exhausting spring spent seeking out online resources and setting up Zoom calls with grandparents, we are grateful—and optimistic—to see our district and so many others work to make the shift toward meaningful virtual learning.

I have three children in public schools in Philadelphia. After an exhausting spring spent seeking out online resources and setting up Zoom calls with grandparents, we are grateful—and optimistic—to see our district and so many others work to make the shift toward meaningful virtual learning.

But, like so many other parents, we still worry. We worry about how two full-time working parents can provide tech support while managing our own video conference calls and staff meetings. We worry about the psychological well-being of our kids who have spent most of the last six months isolated. We worry about how to make learning come alive when our kids only connect with their teacher through a screen.

After a summer of this worrying, we decided to “pod up” with three other families and hire someone to facilitate and supplement their learning while our kids attend online classes.

For our family, forgoing a pod, while perhaps well-intentioned, would not help dismantle an inequitable system, it would merely act as a salve for my guilt

Along with our “pod partners” we are grappling with the guilt we feel over the privilege we are exercising to give our families this advantage. Pods, as an innovation to address the shortcomings of virtual learning, have become a hot button issue because of what feels like their inherent inequity.

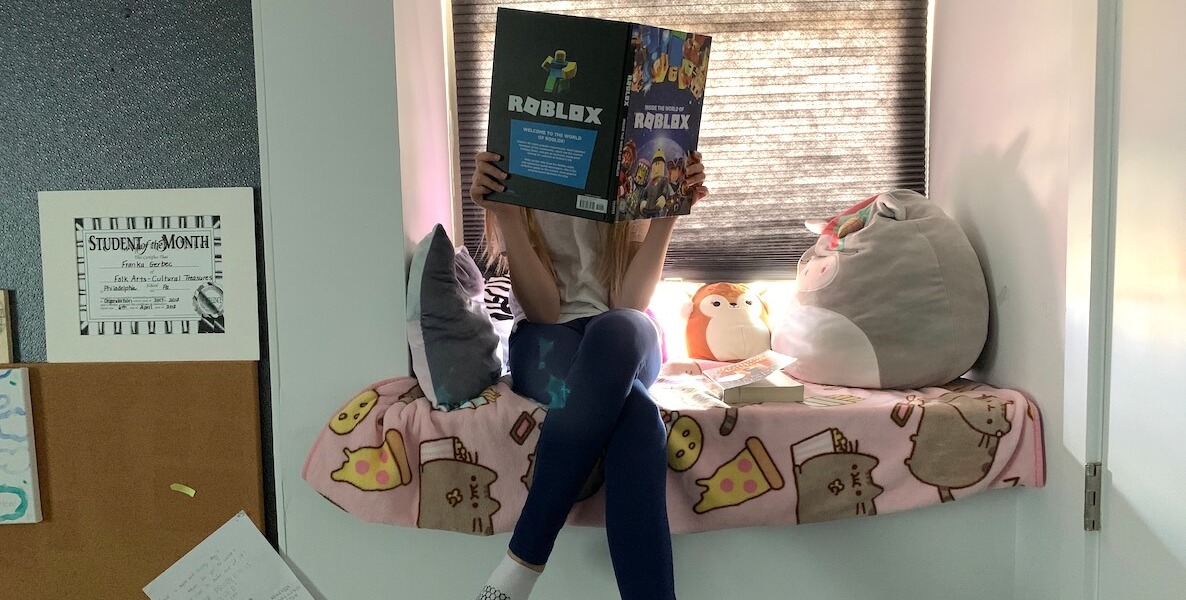

![]() The thing is, even if we passed on the pod, we would find other subtle ways to address the academic and well-being concerns we have for our kids. Last spring, as some school districts halted meaningful virtual instruction over equity concerns, families like ours leveraged flexible work schedules, iPads, and paid online content to fill the time.

The thing is, even if we passed on the pod, we would find other subtle ways to address the academic and well-being concerns we have for our kids. Last spring, as some school districts halted meaningful virtual instruction over equity concerns, families like ours leveraged flexible work schedules, iPads, and paid online content to fill the time.

“To pod, or not to pod” is not a choice between an equitable system and one in which families are left to their own privileged devices. Families with privilege like ours will innovate by leveraging whatever is at their disposal, from technology to part-time work schedules, paid childcare, and more.

The problem we should be solving is not the birth of innovations like pods—which we can no more stop from happening than grass from growing—it is removing the barriers that prevent equal access to those innovations.

So often in the education world (and beyond), we position innovation as the binary opposite of equity. We make valid critiques about the inequitable way in which innovations benefit communities of privilege and exclude others and then push back on the innovation itself rather than expanding access to those innovations.

Instead of asking “how do we run ‘school’ as we know it amidst a pandemic?” imagine if systems and the institutions that support them sought out and embraced innovations like pods and mustered their intellectual and financial capital toward ensuring every student could benefit from a good idea.

Imagine if systems and the institutions that support them sought out and embraced innovations like pods and mustered their intellectual and financial capital toward ensuring every student could benefit from a good idea.

Districts and forward-thinking funders could keep equity at the forefront and innovate by helping network families with similar risk profiles, identifying networks of teachers-to-be to help facilitate small group home instruction, making funding available for art supplies, negotiating access to closed-off spaces, sponsoring “pod leader” training and more.

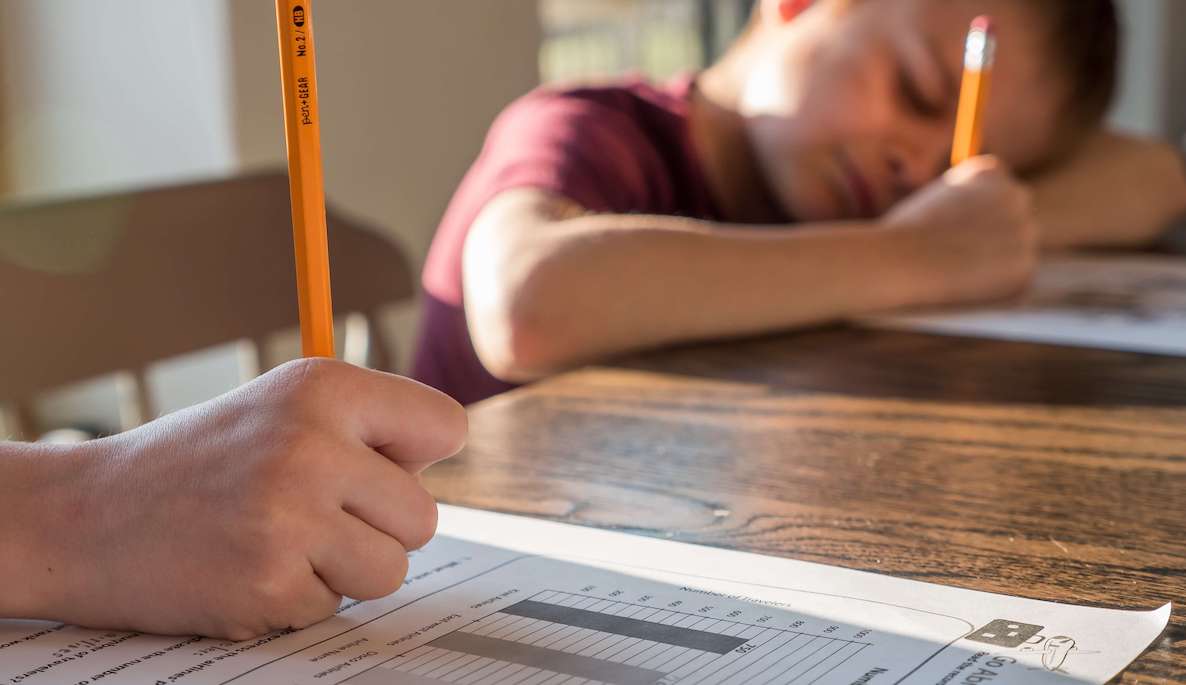

![]() We should aim higher than trying to move what was school online. When we embrace innovation and re-gear institutions to focus on removing barriers to those innovations, we can tap into the assets of communities who haven’t had access to those innovations and go farther than solving the immediate crisis. We can reinvent the system to be better for all.

We should aim higher than trying to move what was school online. When we embrace innovation and re-gear institutions to focus on removing barriers to those innovations, we can tap into the assets of communities who haven’t had access to those innovations and go farther than solving the immediate crisis. We can reinvent the system to be better for all.

When innovation occurs, we waste energy pushing back in the wrong ways. For our family, forgoing a pod, while perhaps well-intentioned, would not help dismantle an inequitable system, it would merely act as a salve for my guilt.

Innovation is not only inevitable, it is necessary to address longstanding inequities that the pandemic has helped bring into stark relief. So I am focused instead on removing barriers to innovations like pods.

Innovation does not cause inequity; unequal access to innovation does. My challenge to funders and to school systems is to find ways to make the benefits of innovation—in the case of pods, that means academic support, childcare, and psychological well-being—accessible to every family.

Mike Wang is a former teacher living in South Philadelphia with his wife and three kids, all of whom attend Philadelphia public schools. He’s a partner at Building Impact and works with philanthropists to make change happen for the issues that matter most.

Photo by Jessica Lewis on Unsplash