There are a couple of tax reform proposals in the mix in this year’s city budget debate, with a short window of opportunity presented by relatively flush city coffers for elected officials to make a smart investment in the city’s economic competitiveness.

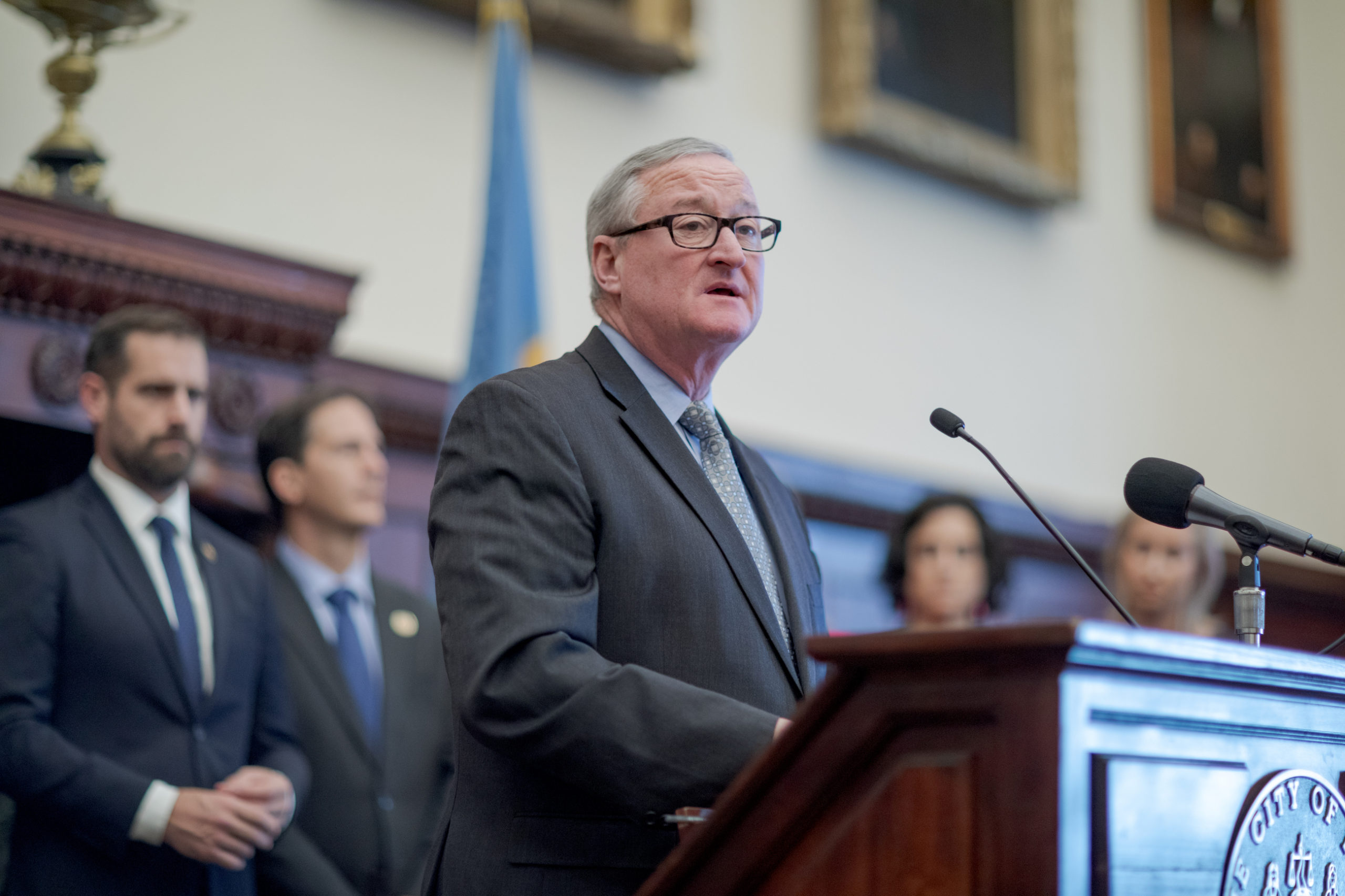

As we’d written previously, there are dueling proposals from Mayor Kenney and also a group of councilmembers including Allan Domb, Katherine Gilmore-Richardson, and Mark Squilla, that would phase in cuts to wage taxes and Business Income and Receipts taxes over several years, with the Domb et al. proposal going further, faster than the Kenney one.

Here’s what elected officials have put on the table so far, from our April story on the mayor’s budget:

“Mayor Kenney’s new plan is a five-year step-down, from 3.8712 percent this year to 3.8245 percent in fiscal 2026. Councilmember Domb’s plan goes further in terms of both the speed of the reductions and the time horizon over which it plays out. In his legislation, the rate in fiscal 2026 is 3.6768 percent, more than 4x the size of the Mayor’s cut. That’s a considerable difference, especially in the context of Wage Tax reductions’ typically glacial pace. Additionally, Councilmember Domb’s schedule runs through FY2042, at which point the rate drops below 3 percent to 2.9000 percent. If we actually made it there, it would be the first time since the late 1960s that the Wage rate would be in the 2s.

The same trends play out in the BIRT plans proposed by the Mayor and Councilmember Domb. BIRT, or the Business Income and Receipts Tax, is made up of two totally separate taxes sandwiched together: the Net Income Tax, which is levied on profits, and the Gross Receipts Tax, which is levied on sales. BIRT has been the ire of local tax policy reformers for decades, since it makes the city an outlier for taxing both of those things—most cities tax one, if they tax businesses revenue at all—and for taxing profits at such a high rate.

Both Domb and the Mayor’s BIRT plans leave the Gross Receipts rate where it’s been for a while at 0.1415 percent but their plans for Net Income differ in ways that mirror their Wage Tax plans. The starting point on Net Income is 6.2 percent, with a scheduled reduction to 6.1 percent in fiscal 2024. The Mayor’s plan drops Net Income to 5.25 percent in fiscal 2025, while Domb’s plan puts Net Income at 4.92 percent that same year, but then goes all the way down to a flat 3 percent in fiscal 2031.

In another corner, there are members who are either opposed to this general flavor of tax reform, or who would rather use any and all surplus dollars for restoring other spending, or some combination of the two.

One of the better points that the critics have—in addition to the business competitiveness case for well-funded and well-functioning city services, schools, and other public amenities—is that the practical impact for individuals from the mayor’s proposal would be very minimal in the near term, especially for the wage tax cuts, amounting to less than $20 a year in most cases.

This week, 7th District Councilmember Maria Quinones-Sanchez pointed out that the wage tax reduction in particular was like buying people three cups of coffee a year, and it would be better to really try and accomplish something more specific and targeted as opposed to a more symbolic strategy that does a little bit for everybody while not really moving the needle much at all.

“The savings from the proposed wage tax reductions would provide approximately $14 annually for the average median household earning $45,927 in the upcoming fiscal year.

Councilmember Maria Quiñones-Sánchez equated the wage tax cut for the average homeowner to “buying people three cups of coffee.” She said the Kenney administration was not aggressively helping Black- and brown-owned businesses, whose biggest liability is the net-profits portion of BIRT.”

Even wage tax reform evangelists admit that cuts three places to the right of the decimal are more symbolic than significant and are ultimately unlikely to impact either employee- or employer-side decision making. They would love to see larger cuts, of course, but major shifts are structurally difficult when a 3.8 percent tax brings in over $1.5 billion dollars a year. There just isn’t much wiggle room, so you land at three cups of coffee per taxpayer, and a rate schedule that takes 20 years to make a real dent.

Conversely, the net income tax is a whopping 6.2 percent, but only brings in about $350 million per year. This means that a relatively large rate reduction is possible with a relatively small investment of front-end tax revenue. And because that revenue translates to materially significant savings at the per-business level, you are likely to see more positive behavior changes that are noticeable at the neighborhood- and corridor level.

Conversely, the net income tax is a whopping 6.2 percent, but only brings in about $350 million per year. This means that a relatively large rate reduction is possible with a relatively small investment of front-end tax revenue. And because that revenue translates to materially significant savings at the per-business level, you are likely to see more positive behavior changes that are noticeable at the neighborhood- and corridor level.

As Councilmember Quiñones-Sanchez notes, that is because net income most directly impacts small-but-growing businesses, particularly businesses owned by Black and brown residents. For these businesses, the ability to hold onto an extra 2 or 3 percent of their profits increases the likelihood that they’ll be able to hire or expand, and reduces the likelihood that they will move outside the city as they become successful. And if it assuages the anti-tax reform crowd, even with a significant Net Income reduction, Philadelphia will still have the highest municipal business taxes of any major city outside New York.

RELATED: 19+ Black-owned businesses in Philadelphia that give back

Early analysis of the migration changes in 2020 found that most individual relocations took place within the same region—something that wouldn’t necessarily be a problem were it not for the high level of tax base fragmentation in Southeastern Pennsylvania. It may all be the same labor market, but those location decisions matter a lot for which local government a person or business pays taxes to. Especially when Philadelphia is such an outlier, with respect to business income burden, compared to peer cities.

The state of Pennsylvania should try and make that less of an issue on the fragmentation side too, but it’s still the case that Philly is never going to have the luxury of being indifferent to the regional business and residential location trends. Currently the suburbs have a disproportionate amount of the high-paying jobs and residents, and for so many reasons—economics, climate, tax base—it would be desirable for Philadelphia to try and improve our relative competitive position on both cost and value compared to the suburban governments.

The Citizen is one of 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push towards economic justice. Follow the project on Twitter @BrokeInPhilly.

Jon Geeting is the director of engagement at Philadelphia 3.0, a political action committee that supports efforts to reform and modernize City Hall. This is part of a series of articles running on both The Citizen and 3.0’s blog.

Photo by Blogging Guide / Unsplash