Nicodemus Madehdou first mentioned “Keeper and the Soldier” to me when I was interviewing him about his work on ME.mory, an app that helps users keep track of their day. Madehdou is a relatively soft-spoken 20-year-old kid, and responds to questions as though he got them months in advance—no stopping, no grasping for answers, no saying “like” 30 times as he scrambles to get his thoughts together.

But when he brought up the new game his development outfit, Jumpbutton Studio, is working on, he couldn’t really contain himself. He compared it to one of the biggest video game hits of 2016. He hyped it up as something entirely different from anything he or anyone involved with his studio had ever tried. He barely gave any details, attempting to lend the game an aura of mystery, the kind of thing that goes out the window a bit when you’re clearly giddily worked up about something.

And he should be. For a young company that’s focused mostly on small, easy-to-play games and as a contractor for third-party development, a full-on action/adventure and platforming game is a big step—one that could launch his eight-year-old company into the big leagues.

Madehdou, now 20, started Jumpbutton in 2009, when he was still in middle school. Back then, it was a loose group of friends working on growing their development skills; as Madehdou and friends entered high school at New Foundations Charter in Philadelphia, the group began to develop apps. Now a freshman at Penn State-Abington, Madehdou still runs his studio from his parents’ house, with developers and designers all over the world, from California to Russia; about five former New Foundations classmates still work with him. Most of their work has been in penny arcade games for Android and iPhone—free games that have simple, addictive gameplay mechanics and make their money off of in-game ads.

About two years ago, Madehdou and his crew decided that they wanted to move onto something bigger, and began entertaining some ideas for software to release on Steam, the premier online video game shopping service. Most of the ideas were generally pretty tame, nothing that could differentiate Jumpbutton from all the other studios that were trying to get a game to catch.

Fong and Jumpbutton are part of a movement among video game developers to tackle subjects that they may not have touched a decade ago. Indie darling “That Dragon, Cancer” is essentially an interactive interpretation of one family coping with their child’s cancer diagnosis; it has sold more than 30,000 copies since its release. The 2015 budget super-hit “Undertale” was about social acceptance and tolerance; it has been downloaded more than 2 million times and has made its creator a multi-millionaire.

But one pitch from freelance artist Jessica Fong grabbed Madehdou’s attention: an action/adventure game set in a fantasy world populated by machines, and navigated by a little girl who could be mankind’s only hope—and that explores themes of surviving child abuse.

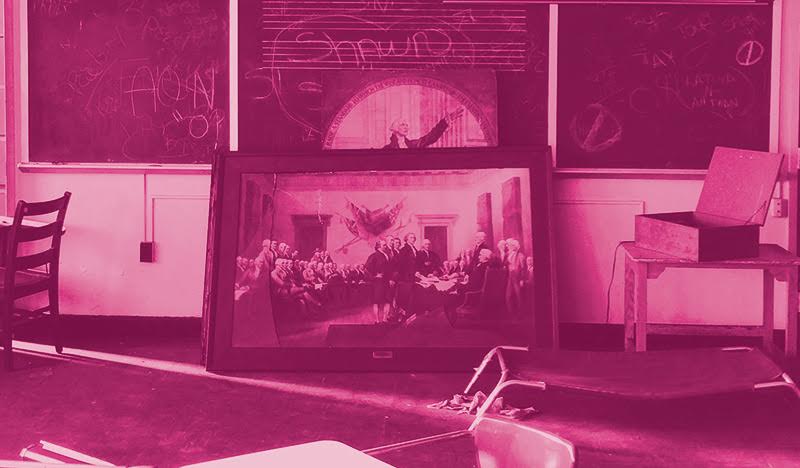

Jessica Fong’s artwork is lush and complex; to look at one of her larger pieces, you’d think it was created by committee, in the comicbook way, with a penciler and an inker. Her style is the kind that big video game companies seek when hiring concept artists: bold, imaginative and decidedly lifelike, it’s the kind of material that massive video game studios would contract and release as a proof of concept for a big-Christmas-release title. Her concept art for “Keeper and the Soldier” is warm, but cluttered and occasionally grotesque.

The game is a narrative about about a girl searching for an artifact that could bring humanity back from the brink of extinction, set in an overgrown, post-apocalyptic dystopia; the art feels personal, with intense vignettes and a lonesome main character named Emi. It takes cues from fantasy-adventure game “Zelda” and 2010’s critical success art game, “Limbo.” Madehdou knew that the character of Fong’s work, as well as the subtext of the game—tackling child abuse—would be the difference between being the ten-thousandth game on Steam to get no traction and making the cut. He put together a small team to develop her story. Two years later, they’re about to launch a Kickstarter to help fund the app’s final development.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-bxG5irwP0M

Fong’s work on “Keeper and the Soldier” is a tribute to the suffering and coping methods of her early childhood. She grew up in California, the daughter of an immigrant from Hong Kong and an American man. Fong says that her upbringing was immensely difficult; her parents, she says, fought regularly, and often experienced explosive culture-clash. Fong says that her parents married after knowing each other only a short while; her mother, she says, was abused by her own father growing up.

Fong is no longer in touch with her mother, and has no plans to attempt to reconcile. That part of her life, she says, is far behind her. Still, she suffers from depression and has had trouble finding full time studio work; she currently freelances, which she says is easier than trying to find a company that will be able to suit her psychological needs.

“My mother suffered from following older generational rules,” says Fong. “She was raised with traditional culture in Hong Kong. There, in order to raise a child, you need to teach them from the very beginning that if you do something wrong, it is your fault, and this is the punishment you get. Growing up, for me, it was always being berated emotionally and vocally, or being beaten.”

Art became Fong’s escape from the reality of her home. She still has binders of material from her elementary and middle school years, which detailed a fantasy world where the lead character was a lost little girl in a world of uncaring, scary machines. She developed this material over the years as she matured from grade-school doodler to AP art kid to digital art student at Cal Poly. Now she’s turning that fantasy world of her childhood into “Keeper and the Soldier,” which she hopes will help others find creative ways to deal with their own trauma.

“More companies are developing games with social themes, and those that aren’t should be,” says Fong. “When I was studying child abuse in college, it came down to generalizations about large populations of kids. You don’t get the stories of those kids, you can’t help them to the extent that you could if you understood where they came from. Video games telling those stories can be extremely powerful.”

Fong and Jumpbutton are part of a movement among video game developers to tackle subjects that they may not have touched a decade ago. Indie darling “That Dragon, Cancer” is essentially an interactive interpretation of one family coping with their child’s cancer diagnosis; it has sold more than 30,000 copies since its release. The 2015 budget super-hit “Undertale” was about social acceptance and tolerance; it has been downloaded more than 2 million times and has made its creator a multi-millionaire. Even top development shops are taking a stab at putting more meaning into their marquee titles. 2K Games’ “Mafia III” may not have received great reviews for its gameplay, but it tried to deliver an expansive, if occasionally corny, narrative about various minority groups making their way through an analogue of New Orleans in the late 1960’s.

“More companies are developing games with social themes, and those that aren’t should be,” says Fong. “We’re trying to understand social issues now more than ever. When I was suffering abuse, I was just one of those statistics. When I was studying child abuse in college, it came down to generalizations about large populations of kids. You don’t get the stories of those kids, you can’t help them to the extent that you could if you understood where they came from. Video games telling those stories can be extremely powerful.”

Socially conscious or not, small development crews stand to make absurd amounts of cash if their Steam-release-that-could game gains traction. The guy who created and developed “Stardew Valley,” a farming game, on his own has pulled in more than $30 million since its release last year. That’s the world in which Jumpbutton hopes to find itself with “Keeper and Soldier.” As it nears the completion of “Keeper and the Soldier,” Jumpbutton is activating a Kickstarter with a goal of raising $50,000. Madehdou says that Jumpbutton is looking for cash to help round the rough edges on the game, and to pay developers as they hit the final stretch. “Keeper and the Soldier” will initially be released on Steam, and if it performs well, Madehdou and company will explore other options for release, perhaps directly on home consoles.

Making a killing off of an independent game is no sure thing. The Steam store is cluttered with have-not games that either couldn’t find a groove or are simply underdeveloped. Madehdou says its worth the risk, though. He wants more than penny games and behind-the-scenes work for Jumpbutton. He wants name recognition; he wants, among other things, office space. And he wants it without compromising the content of his work.

“When we started Jumpbutton, we said we wanted to be socially conscious,” he says, “and we’re not getting away from that.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated Madehdou’s year and school. He’s a freshman at Penn State-Abington.

Photo Header: Whimsical scene from "Keeper and the Soldier."