After the PA Supreme Court released its redrawn congressional map, I was reminded of The Simpsons episode in which Homer, home one Sunday morning instead of in church, is watching the political gabfests on TV when a talking head intones: “Well, let’s define our terms, gentlemen. Are we talking about redistricting or are we talking about reapportionment?”

HEAR THIS ON OUR PODCASTListen

That, I suspect, is how most citizens respond to the back and forth playing out in response to the redrawn map. Because of journalism’s emphasis on bland neutrality, we listen to the charges and countercharges, and we become numb to what’s really at stake. We go in search of football.

Nowhere has this phenomenon been on better display than in the reporting of Congressman Ryan Costello’s critique of the new map; he has called it “racist” because the state would go from two majority-minority districts to one. Who knew Costello was such a fierce advocate of civil rights? I must have missed him on that Selma bridge. Certainly, his faux-outrage would have nothing to do with the fact that the redistricting puts him in further jeopardy at the hands of superstar challenger Chrissy Houlahan?

I was as skeptical as could be about the prospect of the elected state Supreme Court—itself a highly political entity—redrawing our congressional map. But now that it’s out, and contrary to what Costello and the state GOP leaders who are appealing to the U.S. Supreme Court are saying, we should face the fact: It’s been a long time since we’ve seen one…but this is what a solution looks like, people.

Here, hopefully in a way that cuts through the clutter, is why:

What Problem Are We Solving For?

In the day to day he said/she said, the broader problem too often gets short shrift: Our politics are broken. To take just one example from an issue currently in the news: Nearly 9 in 10 Americans have long supported universal background checks for the purchase of firearms. Yet…nada from D.C. Increasingly, our calcified Congress doesn’t represent the will of—not to put too fine a point on it—We The People.

That’s because, as Dave Daley makes clear in his 2015 book Rat F**ked: The True Story Behind The Secret Plan to Steal America’s Democracy, our politicians, looking to ensure their own longevity, became adept at choosing their voters, instead of the other way around. And Pennsylvania Republicans, to their diabolical credit, have led the way in that regard. We’re roughly a 50/50, or “purple” state, and yet our congressional delegation consists of 13 Republicans and 5 Democrats, even though Democratic congressional candidates have gotten more votes than Republicans in recent elections. As Daley amply illustrates, and as the courts have held, that outcome was very purposeful, the product of extreme gerrymandering.

So…what’s the answer?

More competitive elections. The reason we’re stuck in gridlock and partisan divide is because we’re sending representatives to Washington who only have to be responsive to their respective bases. How bad is it? In 1997, according to the Cook Political Report, of the 435 seats in the House of Representatives, 164 were considered “competitive,” that is, the winner was likely to take, at most, 55 percent of the vote. Now we only have 72 competitive districts, a decline over 20 years of 56 percent.

Join FairDistricts PADo Something

How does this relate to the PA Supreme Court’s map?

The map, drawn by Professor Nathaniel Persily of Stanford University Law School, clearly increases competition. Most political analysts predict that, if, as is likely, it survives the Republican challenges, Pennsylvania will either send a 9-9 or a 10-8 Republican majority to represent it in the House of Representatives. That feels pretty, uh, representative in a roughly 50/50 state, doesn’t it?

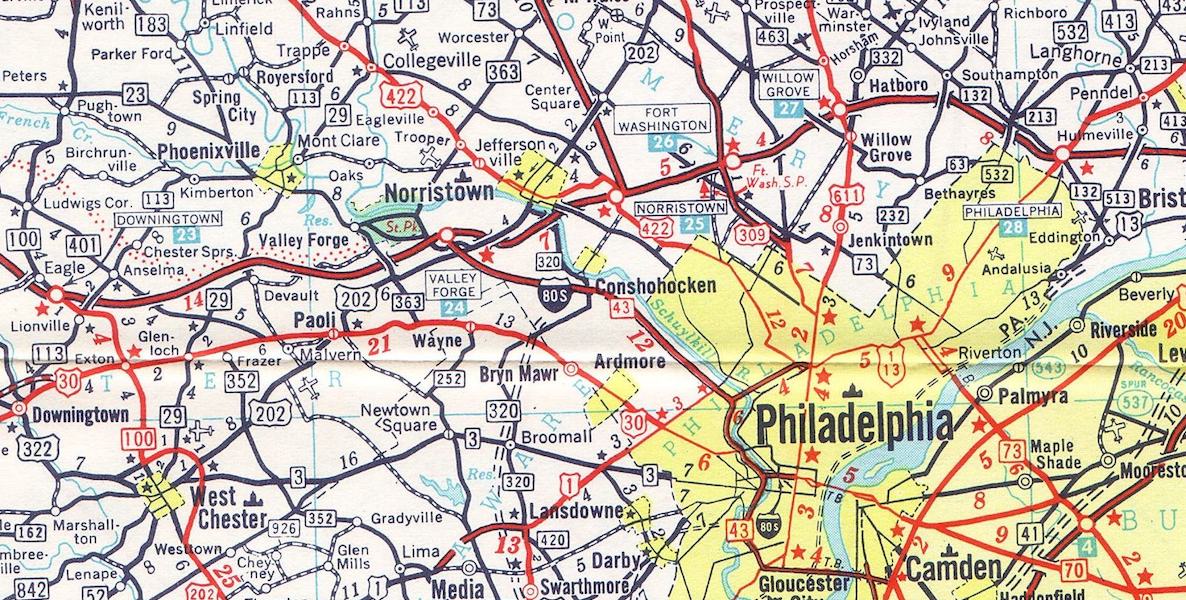

But the map makes a further improvement over its obscenely carved up predecessor. It creates and maintains politically coherent communities. There are two Philadelphia seats, a Montgomery County seat, (which used to be split between five different districts) a Chester County seat, a Delaware County seat (with part of South and Southwest Philly folded in), a Bucks County seat, a Lehigh Valley seat. Yes, owing to the need for districts that are uniform in size, there had to be some cutting and pasting; a part of Montgomery County, for instance, will be folded into Delaware County. But there’s now a geographic logic to our congressional representation. Which makes this all the more delicious: One of the many ironies of Costello’s whining now is that he had been perfectly fine representing a district that illogically ran from the Delaware County border all the way to Lebanon County

Okay, you’re having a lot of fun satirizing Costello as the newest Black Lives Matter member, but what about his point? Is the redrawn map racist?

This is part of the problem with “objective” journalism. It has to report clearly self-interested accusations with a straight face.

Don’t get your hopes up that fixing gerrymandering will fix us, the electorate. We have self-gerrymandered. Increasingly, we’ve chosen to live among the like-minded. Nearly 60 percent of the electorate live in counties that were decided by 20 points or more in 2016; in 1992, the exact reverse was true.

Costello and the GOP’s point is that the old map had two minority-majority districts, and now it only has one. But that’s because the old map had three Philadelphia seats, and now has two. (Effectively, a “black” seat, represented by Dwight Evans, and a “white” seat, represented by Brendan Boyle). Bob Brady’s seat goes away; voters from South and Southwest Philly get subsumed into the Delaware County seat.

Watch David Daley on Comedy CentralVideo

That’s not ideal, but map drawing requires a careful balancing of interests, and one of those is uniformity in size. The best response to the claim from Costello et al is to hold up to inspection their underlying assumption that minority voters are only enfranchised when they’re voting for minority candidates. For 12 years, minority voters sent Brady to D.C. to represent them. Costello, whose federal court filing explicitly complains that the new map would destroy his “incumbency advantage,” (entitled much?), is looking to protect voters who are not—or not yet, anyway—requesting protection.

Besides, with the addition of the Philadelphia voters, there’s a chance that the redrawn Delco seat might actually elect a minority candidate. If the impressive Rep. Joanna McClinton runs, as is rumored, and turns out to be the only African-American candidate in a crowded field, Ryan Costello just might get his minority empowerment wish.

This is Philly. So: What’s the catch?

Ah, yes. The law of unintended consequences. There are two:

First, the courts drawing up congressional maps is a really dangerous precedent About GerrymanderingRead More

Finally, don’t get your hopes up that fixing gerrymandering will fix us, the electorate. We have self-gerrymandered. Increasingly, we’ve chosen to live among the like-minded. Nearly 60 percent of the electorate live in counties that were decided by 20 points or more in 2016; in 1992, the exact reverse was true. Democrats cluster in metro areas, Republicans in rural. Demographers call it “self-sorting,” and it’s not anything that a commission or a court or politicians can solve for.

What they can do, however, is what—surprisingly—the state Supreme Court has done, despite the partisan calls now for their impeachment: Release an intellectually honest attempt to bring competitive elections back to our political marketplace.