By the time Nikolas Cruz walked into a Florida high school with an AR-15 semiautomatic weapon, it was too late to stop him from killing his former classmates. Seventeen people died and several more were injured in minutes, despite an armed sheriff’s deputy stationed outside, school lockdown drills, students taught to crouch in corners and wait for the all-clear.

Be Part of the Solution

Become a Citizen member.Cruz was a disturbed young man who had announced his murderous intentions online, who was reported to the FBI, whose behavior in school and outside showed—in hindsight—the signs of someone on the violent edge. But what if the school had intervened months earlier, when Cruz was still a student at Parkland’s Stoneman Douglas High School? What if the teenager had received counseling and/or medication, had had his guns removed from his home, had connected with adults who made him feel less isolated and hopeless?

Could that have prevented the attack? There’s evidence to show it might have—if done the right way.

“There are many, many, many cases across the country when people came forward when they saw the signs and law enforcement was able to come in and prevent shootings before they happened, and put in place things to get students help,” says Melissa Louvar Reeves, past president of the National Association of School Psychologists.

Hundreds of schools around the country have threat assessment teams, made up of educators, mental health professionals, and police, that identify and manage threatening behavior before it turns violent. The teams are trained to determine if a threat is real or just talk; to assess a student’s mental and emotional state; to take legal action if necessary; and to provide the student with the mental health services needed to get past their anger or isolation.

Prefer the audio version of this story? Listen to this article on CitizenCast below:

In Virginia, which became the only state to mandate threat assessment teams in every K-12 school after the Sandy Hook school shooting in 2012, the results are clear: A University of Virginia study of 1,865 cases in 785 schools found that 30 percent of investigated threats were serious; after the team’s intervention, only one percent of the acts were carried out—and none resulted in the shootings or stabbings that had been threatened.

![]() The research by forensic psychologist Dewey Cornell, director of UVA’s Youth Violence Project, also found that only one percent of students assessed were expelled from their schools, and that there was no racial disparity among those who were found to be an actual threat—a striking difference from the kinds of overzealous zero tolerance policies at many schools. Instead, students were left in school to learn and access the sorts of services they needed to no longer be a threat to themselves or others.

The research by forensic psychologist Dewey Cornell, director of UVA’s Youth Violence Project, also found that only one percent of students assessed were expelled from their schools, and that there was no racial disparity among those who were found to be an actual threat—a striking difference from the kinds of overzealous zero tolerance policies at many schools. Instead, students were left in school to learn and access the sorts of services they needed to no longer be a threat to themselves or others.

“There is no way to 100 percent predict human behavior, “ says Melissa Louvar Reeves, past president of the National Association of School Psychologists and a senior consultant at Sigma Threat Management Associates, which trains threat assessment teams. “But there are things we can do to be proactive. There are many, many, many cases across the country when people came forward when they saw the signs and law enforcement was able to come in and prevent shootings before they happened, and put in place things to get students help.”

Threat assessment has long been used by government, particularly the Secret Service, to intervene when there are threats against politicians; businesses have adopted similar methods to weigh threats against them and their employees. Reeves says a series of school shootings in the 1990s—including at Columbine—prompted the Secret Service to conduct research on the shooters. That study concluded that trained eyes, like an assessment team, might have spotted a danger early on and, possibly, intervened before the attacks.

After Parkland, Florida Gov. Rick Scott allocated $450 million to go towards school safety measures, including the establishment of threat assessment teams in every Florida school to include a teacher, principal, a police officer, human resource officer, Department of Children and Families employee and a Department of Juvenile Justice employee. Each team will meet monthly to assess threats to the school. Several other states have already recommended that districts form assessment teams—though most do not provide funding—and several are now considering making them mandatory, as in Virginia and now Florida.

![]() School assessment teams have different models; Cornell’s is different than the one Sigma has helped the state of Virginia deploy in its schools. But they work in essentially the same way. Children are not subtle; they rant on social media, threaten each other in the hallways, boast about their guns. It’s usually other students who see these rants, and who then report them to an adult at school. Once alerted, the assessment team steps in to investigate. Reeves stresses that professional training is key here: Every member of the team undergoes research-backed training in how to spot and manage a threat, often in the least invasive way possible.

School assessment teams have different models; Cornell’s is different than the one Sigma has helped the state of Virginia deploy in its schools. But they work in essentially the same way. Children are not subtle; they rant on social media, threaten each other in the hallways, boast about their guns. It’s usually other students who see these rants, and who then report them to an adult at school. Once alerted, the assessment team steps in to investigate. Reeves stresses that professional training is key here: Every member of the team undergoes research-backed training in how to spot and manage a threat, often in the least invasive way possible.

Usually, as Cornell’s research has shown, the threats are meaningless, just the raving of an angry kid. At times, though, the team will discover a student on the verge of an explosion. For instance, Reeves says she once worked in a school where a student was boasting about a “hit list.” After other students told teachers about the threat, the assessment team intervened, got the kid mental health care, and diffused the situation before he could finalize his plans. A Boston Globe article on threat assessment teams last week mentioned another case, in New Bedford, Massachusetts, in which a group of students in 2001 had stockpiled ammunition and bomb-making instructions in a plot to kill their classmates, Columbine-style. One of the students told a teacher, and the plot was foiled.

“Connectedness is the number one thing that prevents kids from causing harm to themselves and others,” Reeves says. “It’s when people reach a place of helplessness and hopelessness that they think they’ll carry out that act. Assessment teams look at the individual and what’s going on in themselves, at school, home, socially. The goal is to ID concerns, and get the student help, and get them off the pathway to violence.”

In a statement to Congress last week, Cornell pointed out something that bears repeating: School shootings, even in America, are rare. They make up a very small percentage of the total deaths or injuries by gun. “Over the past 20 years, the United States has experienced an average of 22 students murdered at school each year,” Cornell said. “However, outside of schools, 1,480 students are murdered each year. In other words, students are 67 times more likely to be murdered outside of school than at school.”

Spending billions of dollars on locks, and drills, and metal detectors might keep more kids alive in the event of the rare school shooting. Spending money to prevent kids from getting to that point can have ripple effects outside of the school walls—in reducing violence on the street, and treating the trauma that precedes it.

That is certainly true in Philadelphia, which has not experienced a targeted school shooting like that in Parkland—but where hundreds of (often) young people are shot every year in their own neighborhoods. Schools are relative safe havens; the streets around many city schools are not. Spending billions of dollars—Cornell estimates $5 billion since Sandy Hook—on locks, and drills, and metal detectors might keep more kids alive in the event of the rare school shooting. Spending money to prevent kids from getting to that point can have ripple effects outside of the school walls as well—in reducing violence on the street, and treating the trauma that precedes it.

It is increasingly evident that mental health issues are among the biggest hurdles for learning, and teaching, in many of our public schools—something that even students recognize, as evidenced by their testimony at a hearing convened by Councilmenber Helen Gym last week. “Over 100 students came to the roundtable and called out for more counselors, social workers and support staff in their schools,” Gym said in a statement. “These crucial student needs must be heard by our District leaders because they have such a profound impact on young people’s sense of safety, belonging, and hope within their schools.”

![]() It shouldn’t take a deranged student with a gun in school for us to act on ensuring the mental and physical safety of our children. But it also does take resources beyond what we have seen in the last several years—as well as a commitment to spend some of the new proposed tax revenue on needed support staff in school. We choose our priorities, and literacy is a laudable one for a school. Unfortunately, we don’t have the luxury of focusing just on the basics in Philly classrooms.

It shouldn’t take a deranged student with a gun in school for us to act on ensuring the mental and physical safety of our children. But it also does take resources beyond what we have seen in the last several years—as well as a commitment to spend some of the new proposed tax revenue on needed support staff in school. We choose our priorities, and literacy is a laudable one for a school. Unfortunately, we don’t have the luxury of focusing just on the basics in Philly classrooms.

“I talk about the 4 ‘Rs’ instead of 3: Reading, ‘Riting, ‘Rithmetic, and Resiliency,” Reeves says. “We need to teach conflict resolution, empathy, collaborative problem-solving in schools. We need more resources in schools to bring this in early on, so we can connect people to what they need before they become a danger to themselves or others.”

There is some indication that federal funding for threat assessment teams may be on the horizon. Reeves says Congress is considering increasing funds for Title IV’s support of safe and healthy schools and students, and opening up Title II money—usually reserved for teachers—to mental health support staff. (The Stop School Violence Act, making its way through Congress, focuses mainly on physical safety like door locks, metal detectors and school resource officers.) If that happens, it could provide an avenue for mental health support in Philly schools, possibly as soon as next year.

And why not? It’s one of those things that seems to fits everyone’s box: It isn’t about guns; it’s about mental health. As Cornell puts it: “Prevention must start long before there is a gunman in the parking lot. It must start with helping all children to be successful in school.”

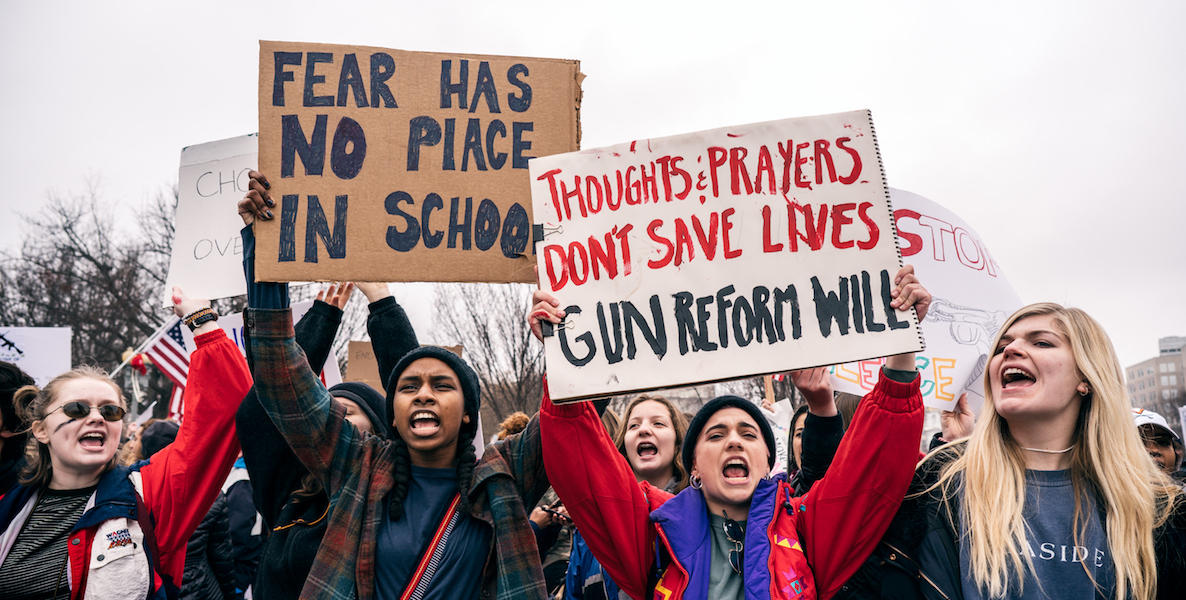

Photo via Wikimedia Commons