Every four years, the city receives a mind-numbing reminder of the state of civic disengagement: Voter turnout numbers for electing a Philadelphia District Attorney.

For the past several decades, whenever Philly has gone to the polls to choose a chief law enforcement officer, voter turnout reliably sinks to a four-year low. In fact, the city had three consecutive DA elections in recent memory — across the early 2000s — where turnout never exceeded 13 percent (one in eight people!), at a time when local crime rates were national news.

It was also true in 2017, even after George Soros funnelled millions of dollars into the race, despite Larry Krasner’s unconventional and polarizing campaign, and regardless of a resurgence of local political organizing in the wake of Donald Trump’s ascent to the White House. That year, turnout barely eclipsed 20 percent — which, at the time, was the highest mark in two decades for a DA’s race.

But what if there was an easy way to bolster turnout, potentially by the thousands, one that doesn’t involve an army of canvassers or the influence of a billionaire?

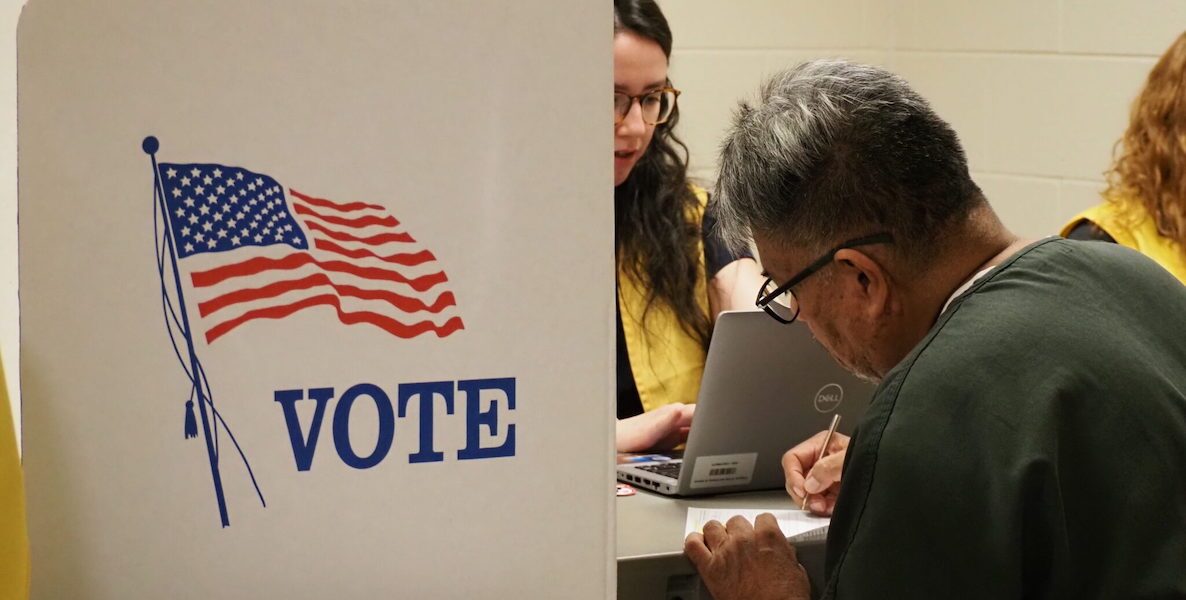

In 2024, lawmakers in Colorado achieved this by catering to a constituency that’s rarely heard from: people in jail. The Colorado legislature passed a first-in-the-nation bill that requires county jails across the state to establish polling places for prisoners. It was preceded by a “Confined Voter Program” in Denver, which launched in 2020 and served as a proof of concept. As is true in PA, the majority of people held in county jails are awaiting trial, so have not been convicted of any crime. The rest of the population is almost entirely made up of people serving misdemeanors.

In CO and PA, individuals in both those groups have a constitutional right to vote, even while behind bars, which is typically facilitated through mail-in ballots. However, due to institutional barriers and information gaps, that right is rarely exercised.

Prior to Denver’s program spurring the state forward, the voter participation rate of the jailed population in Colorado was typically in the low single digits, often less than 3 percent. Many opponents of the voting access bill, some of them wardens and sheriffs running those correctional facilities, argued that poor turnout was a function of low demand — prisoners not being interested in democracy.

“Those folks had an ability to have their voices heard in their communities for the first time.” — Kyle Giddings, Colorado Criminal Justice Reform Coalition

After the statewide law took effect, the overwhelming results have turned skeptics into believers. “I had tears in my eyes,” Tiffany Lee, a county clerk and elections official in CO’s La Plata County told Bolts magazine. After initially resisting the statewide mandate, Lee celebrated the fact that 43 people voted from La Plata’s jail last year, five times the number that did so in 2022.

The results were even more drastic elsewhere in the state. Overall, voter turnout among prisoners swelled by 2,000 votes, nearly a 1,000 percent increase across all correctional facilities.

“Those folks had an ability to have their voices heard in their communities for the first time,” says Kyle Giddings, civic engagement coordinator for the Colorado Criminal Justice Reform Coalition, a nonprofit focused on justice-related causes in the state.

And while last year was a presidential election, the impact of CO’s mandate could be even stronger in future municipal elections, when races — like for District Attorney and judicial positions — can have a direct effect on the voting bloc that the law is designed to help.

“Guys will come up and talk to me and be like, ‘Why should I vote?’ Well, if you don’t like how your case is going, you can vote against your DA. You can make a statement, and say, Hey, I’m affected by this system, and so my voice in the solutions should also be heard,” says Giddings.

A lot of people believe that prisoners — who’ve disregarded the law, or been accused of it — have forfeited their rights and should not have any say in electing lawmakers. But voting access for prisoners is not just for them. It’s also about public safety. The re-arrest rate for returning citizens who get to vote is substantially lower, according to researchers. And studies suggest that voting is one of the best ways to boost prosocial behaviors that allow for prisoners to successfully reintegrate into society later on.

Start local

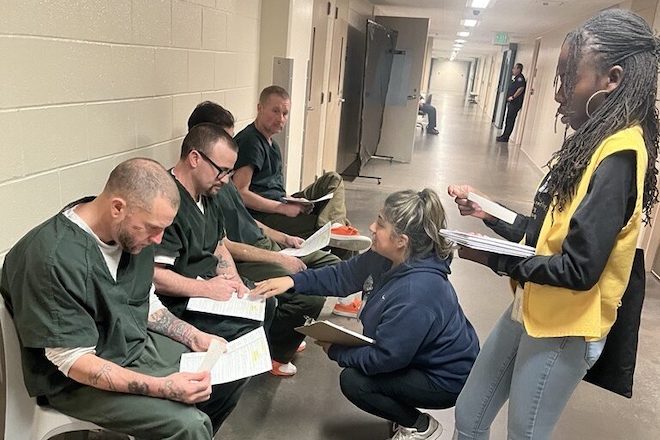

It was while he was incarcerated himself that Kyle Giddings saw the need for more voter education for prisoners. “I was waiting to be picked up at the halfway house at the county jail here in Colorado when I had my first conversation around voting rights,” he says. “There was this fella named Jeff, and we always talked about everything — it was that, or watching Pawn Stars — and he mentions that he’s never going to be able to vote, because he had a felony [on his record]. And I knew that wasn’t true.”

Like in PA, almost nobody is disenfranchised in CO on a permanent basis. Even with a felony conviction, you can vote while on probation or once you’re done serving a sentence (one exception: a felony conviction for violating election laws). Those jailed for a misdemeanor or awaiting trial never lose their right to vote. But like Jeff at the halfway house, Giddings recalls, there’s a wealth of misinformation and false presumptions that get in the way.

“Suddenly I had 20 to 30 guys — from young to guys in their 50s, many of whom had never voted before — listening. And that’s what kind of launched me on my path of jail-based voting.”

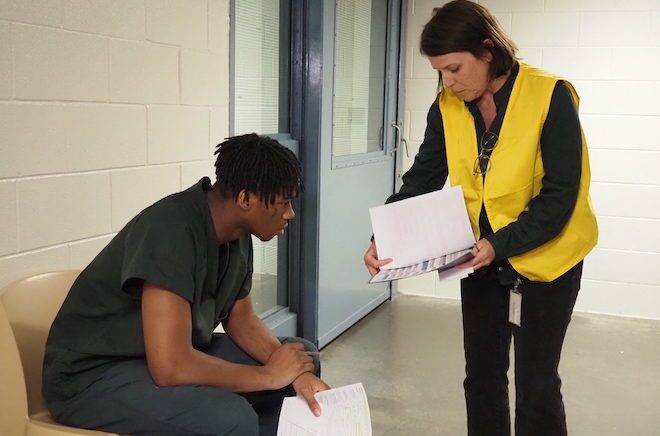

It’s not only prisoners who need more education. According to a Harvard Kennedy School case study about Denver’s Confined Voter Program, one of the traditional impediments to voting access was a lack of knowledge on behalf of the staff inside jails. Plenty of incarcerated people who sought assistance in obtaining a mail-in ballot hit a roadblock: “Some staff members mistakenly believing that people incarcerated in jails are ineligible to vote or lacking the knowledge to facilitate the voting process on their behalf,” researcher Tova Wang wrote in the case study.

“Known as de facto disenfranchisement, this disproportionately impacts low-income Black and Latino individuals who,16 because of historical and present-day racist policies and practices, are at a greater likelihood of being ensnared in the criminal justice system.”

Only a few years before Giddings left the halfway house and never looked back, the CO state government launched a Blue Ribbon commission to explore ways of strengthening voting rights. One of the recommendations, to clear up ambiguity around the voting rights of incarcerated people, made its way into an omnibus bill in the state legislature that led to a momentous change: the Colorado Secretary of State officially removed the word “misdemeanor” from its list of disenfranchising exclusions.

“Studies show that having the right to vote shapes community re-entry experiences and is linked to intentions to remain crime-free.” — The Sentencing Project

However, almost two decades later, advocates of that policy change still waited for a surge in ballots being submitted from behind bars. In 2018, fewer than 300 incarcerated people (out of a population of roughly 29,000 in local and county jails in Colorado) cast a ballot.

Colorado Common Cause, a nonprofit focused on government accountability, published a report in 2020 that evaluated plans for voter access for the 57 Colorado counties with jails. Although a lot of county officials had previously claimed that there were no barriers to mail-in ballots, the report found that roughly half of the jails made no effort to ensure that their populations had access to ballots.

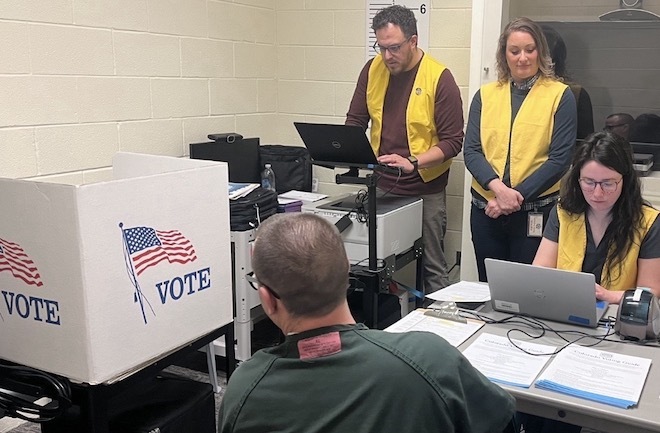

Not long after that report, the correctional department in Denver, the state’s largest city, vowed to do better. In 2020, Denver voluntarily launched the Confined Voter Program, a partnership with the League of Women Voters and CCJRC. Together, the organizations set up polling places in each of the city’s two jails. Denver joined a handful of local jurisdictions to allow in-person voting for those in jail (Cook County, Illinois was the first, followed by Washington, D.C. and Los Angeles, California).

The Confined Voter Program was an immediate success. About 10 percent of Denver’s jailed population voted in year one, breaking a record. “It was literally as smooth as butter, like not a single hitch,” says Giddings. From there, turnout rose dramatically in subsequent years. In the April 2023 Denver municipal election, the voter turnout rate inside the jails rose to 78.4 percent, which was more than double the rate of the general population.

The system worked so well, in fact, election officials and advocates were inspired to replicate the initiative statewide.

Democrats, who control both chambers of the CO legislature, were able to pass the 2024 bill requiring polling places in jails despite some pushback. According to Giddings, the key to convincing enough state legislators was the success of the case study in Denver — which was achieved through minimal resources and staffing. “We were able to do six-plus hours of in-person voting [at the jails] with only two correctional officers, along with four election workers, and this was during the height of Covid-19,” says Giddings.

Before the bill was passed, some clerks and sheriffs testified against it by claiming that in-person voting would cost each county about $2,000 per voter. But after the fact, Tiffany Lee, the clerk from La Plata County, says it cost no more than $200 total for the entire day.

“We had a structure established that people in other counties could rely on and change to fit the needs of their jails, and was proven to work,” says Giddings

The path in PA

On the day of the May 20 primary election in Philly, there will be roughly 3,700 people, most of them eligible voters, residing on State Road, the majority of whom have not been found guilty of a crime. (Those numbers, which have dropped to historic lows, have traditionally been higher.) They have more at stake than the average voter, because this election cycle features races for both DA and a host of judicial seats. The justice system is a reality that those voters are living.

Yet, history suggests that only a small fraction of them will exercise their constitutional right to vote. According to the nonprofit All Voting is Local, roughly 4 percent of PA’s incarcerated population requested a mail-in ballot during the 2022 election. Far fewer of them ultimately submitted one.

One of the biggest hurdles throughout the state, says Representative Rick Krajewski (D-Philadelphia), is a stigma that prisoners often internalize which strips them of knowledge about their rights. “There is still a big cultural belief that incarcerated people are bad people and in America, we punish by taking things away,” he says. “Being in jail is a deeply alienating and isolating experience.”

Krajewski is one of the prominent voices in Harrisburg who’s been working to ensure voting rights for individuals inside the justice system or those who’ve reintegrated. He has sponsored a number of bills that address problems of access and education, including one last year (an idea borrowed from Michigan) that would enable automatic voter registration for returning citizens.

This year, several states have taken after CO and introduced legislation to implement polling places at jails, including New York and Rhode Island. Could a similar initiative pass muster in PA’s state government?

While Krajeski was not closely familiar with the details of the CO program, he thinks it would be a welcome addition to PA. “Anything that can one, increase voting, and two, destigmatize the idea that because you’ve entered our criminal justice system your rights are less than [others] is worth pursuing,” says Krajewski.

“You can make a statement, and say, Hey, I’m affected by this system, and so my voice in the solutions should also be heard.” — Kyle Giddings

Moreover, he believes there could be an appetite for such a reform. Over the past few years, Krajewski has met with dozens of wardens and correctional leaders throughout the state to gauge their commitment to voter participation. The bright spots, like Centre County, where prison officials took it upon themselves to institute a voter education program, have led him to believe that there’s reception and openness to his ideas.

“Wardens often tell me, I’m all for more programming,” he says. “There are places that are expanding access without breaking the bank and without burdening staff. It’s about having the will and the conscience to do it.”

Another incentive for correctional officers is that voting can be a powerful deterrent to recidivism. The Sentencing Project did an analysis of academic research on the topic and found a strong correlation between voting access and improved public safety: “The right to vote was a fundamental component of developing a prosocial identity, whereas being restricted from voting reinforced an outsider status — feeling like a partial citizen,” the report says. “Studies show that having the right to vote shapes community re-entry experiences and is linked to intentions to remain crime-free.”

Also, voting is habitual: Showing up at the polls increases the likelihood that the same person will return to vote again, studies have shown. In other words, the more you participate and have a meaningful experience, the more likely it is for voting to become ingrained behavior. Physically going to the polls has an especially positive effect.

Of course, the policy might have a harder time getting passed in PA’s divided government. Like a lot of pushes to expand voting rights, there’s an underlying assumption among conservatives that these policies will imperil them, because these new voters would have an allegiance to Democrats, who’ve advocated for them.

But that’s not what’s played out in CO. “That was the narrative that was flying all over the place: The Democrats are just to stuff ballot boxes, just like on campuses,” says Giddings.

After the bill was implemented, one of the first counties they got data back on was Jefferson County — which has been won by the Democratic candidate in each of the past four presidential elections. “They were able to show that 70 percent of the people who voted from the jail voted Republican, not Democrat,” Giddings says. “And I was then able to go to Republicans and say: Don’t disenfranchise your own voters.”

Every Voice, Every Vote funds Philadelphia media and community organizations to expand access to civic news and information. The coalition is led by The Lenfest Institute for Journalism. Lead support for Every Voice, Every Vote in 2024 and 2025 is provided by the William Penn Foundation with additional funding from The Lenfest Institute for Journalism, Comcast NBC Universal, The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Henry L. Kimelman Family Foundation, Judy and Peter Leone, Arctos Foundation, Wyncote Foundation, 25th Century Foundation, and Dolfinger-McMahon Foundation.

Every Voice, Every Vote funds Philadelphia media and community organizations to expand access to civic news and information. The coalition is led by The Lenfest Institute for Journalism. Lead support for Every Voice, Every Vote in 2024 and 2025 is provided by the William Penn Foundation with additional funding from The Lenfest Institute for Journalism, Comcast NBC Universal, The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Henry L. Kimelman Family Foundation, Judy and Peter Leone, Arctos Foundation, Wyncote Foundation, 25th Century Foundation, and Dolfinger-McMahon Foundation.

![]() MORE ON GETTING AMERICANS TO VOTE

MORE ON GETTING AMERICANS TO VOTE