You’d have thought J.J. Balaban would be smiling. I had run into the ace political consultant at Famous Deli last month, during the traditional election day lunch that features a cadre of political insiders scarfing down oversized sandwiches and comparing notes. Balaban had been Rebecca Rhynhart’s message guru, and, though we didn’t know the results yet, his candidate had run an impressive campaign, the weather was good, and anecdotes from Center City polling places were showing that turnout might exceed the lowest of expectations.

Yet, as bold-faced names ranging from Neil Oxman, Balaban’s mentor, to Comcast’s David Cohen ordered artery-hardening sandwiches slathered in Russian dressing and cole slaw, Balaban warned me not to get too carried away celebrating that we were headed to what would ultimately turn out to be all of 17 percent turnout. “There’s only one way to make Philadelphia politics more democratic,” he said. “We should adopt a ‘Top Two’ primary system. That would undermine the ward system and enfranchise Republicans, Independents, Berniecrats and millennials.”

What is Top Two? Well, you’ve heard the calls for Open Primary reform, right? Most recently, Chris Satullo made the argument for it in the pages of the Inquirer. As Satullo explains, one type of open primary allows for independents to vote in democrat and republican primaries.

Another type, the Top Two approach, adds a nonpartisan element: In Top Two elections, all candidates are listed on the same ballot. The top two vote-getters, regardless of party, then advance to the general election. Forty states run some form of open primary, and in Top Two cities like Los Angeles, San Francisco, Boston and Atlanta, two candidates belonging to the same political party have actually won top-two primaries and then faced off in the general election.

Why is this needed? Because our closed system works counter to the public interest. In last month’s primary, 68 percent of Philadelphia’s 1,526,006 residents were registered to vote; of those, 17 percent actually did. That means that all of 11 percent of the city’s population showed up to essentially choose our next District Attorney, kind of an important office.

Top Two races have mitigated against the rise of the extremes—Tea Partiers on the one hand, nihilistic lefties on the other—and elected reasonable centrists, as a 2015 congressional race case study from Washington State illustrates.

And that is the usual script. Instead of a competitive primary leading to a competitive general election, we tend to have one fractured election with low turnout—the primary—and one meaningless election in the general, which coronates the Democratic nominee. A Top Two system, on the other hand, both expands the number of people that can vote and requires someone to put together majority support.

Then-Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger pushed California to adopt a Top Two primary system in 2010, and the evidence is convincing that it has led to more candidates running, helped elect more moderates from both parties, and empowered the fastest growing political designation in the country—independents.

Incumbents haven’t fared well under California’s new system. In the five elections preceding the adoption of Top Two, only 8 percent of Assembly members and 2 percent of state senators faced primary challenges from within their party. Since 2010, 28 percent of state senators and 21 percent of Assembly members have faced same-party challenges.

“The system has encouraged more candidates to run,” Eric McGhee, a research fellow at the nonpartisan Public Policy Institute of California, told the Los Angeles Times.

And Top Two races have mitigated against the rise of the extremes—Tea Partiers on the one hand, nihilistic lefties on the other—and elected reasonable centrists, as a 2015 congressional race case study from Washington State illustrates.

Balaban argues that our District Attorney election makes plain the need for a Top Two system. “If Seth Williams hadn’t been indicted, I’m convinced he would have continued his campaign and won a plurality of the vote in such a large primary field,” he says. “That would have been terrible for the city. But in a Top Two system, whoever made it into the run-off would have been the heavy favorite to get a majority of the voters to support him or her over Seth.”

If we had a Top Two process here, we’d now have a general election District Attorney race between Krasner and Joe Kahn, a potentially more competitive race than one between Krasner and Republican nominee Beth Grossman in a city where Democrats outnumber Republicans nearly 8 to 1.

If we had a Top Two process here, we’d now have a general election District Attorney race between Krasner and Joe Kahn, a potentially more competitive race than one between Krasner and Republican nominee Beth Grossman in a city where Democrats outnumber Republicans nearly 8 to 1. It’s too late to change the rules of the game for the general election, but all the tumult between the Fraternal Order of Police and Krasner—faux-harmonious soundbites notwithstanding—could be a harbinger of a grand bargain, Balaban suggests.

The idea is this: Republicans in Harrisburg—who would have to sign off on the change—are convinced by the FOP that it would be in their interest to adopt the Top Two primary system, since the closed primary system is what gave them their arch-nemesis, Krasner. In addition to Republicans, there would be something in a move to a Top Two system for other groups, including millennials (because they tend to register as Independents in greater numbers) and Berniecrats (because Sanders performed better in open primaries last year).

Adopting a Top Two system here may sound politically far-fetched, but Satullo is thinking the same way. Noting that Pennsylvania is one of only 10 states still “stuck in the electoral dark ages,” he writes: “Would the capital’s Republican mahoffs, who so hate Philly’s Democratic machine, be open to this notion: How about trying open primaries exclusively in ‘cities of the first class,’ i.e. only in Philadelphia?”

Not likely, I know. But, in the American city where it was born, it’s always fun to dream of a flourishing democracy.

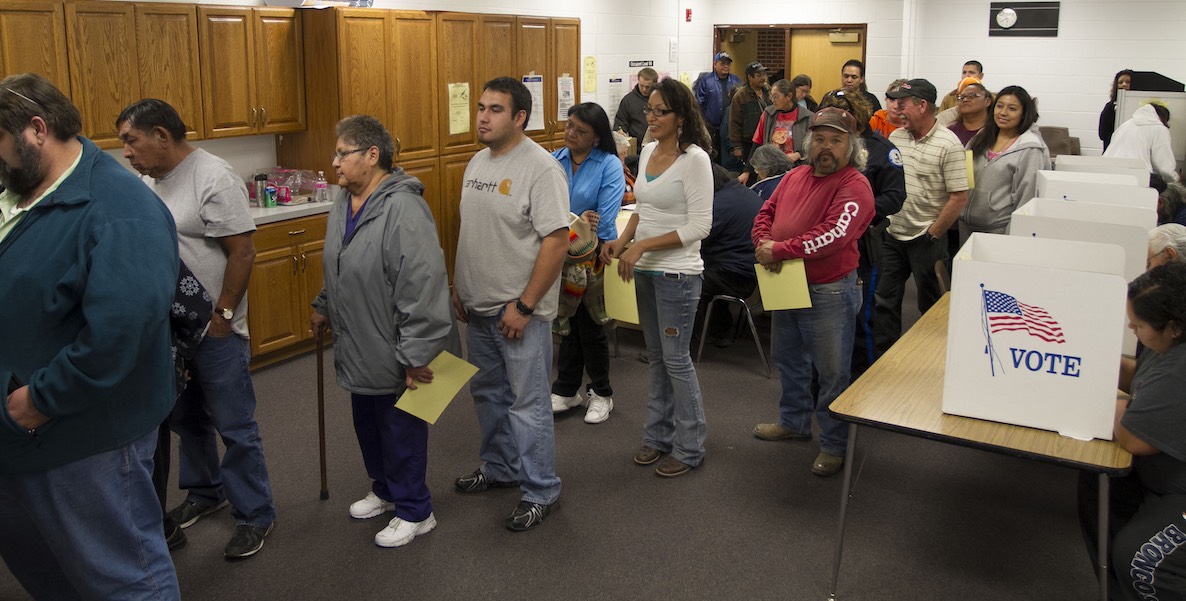

Header photo: