Two groups of fifth grade students, eager to be outdoors again after the recently terminated summer vacation has confined them to classroom desks, gather on a grassy lawn outside the historic Stenton house in Germantown. One group represents the Delaware Indians who once lived in this region; the other acts as the colonial agents of John and Thomas Penn (sons of Pennsylvania founder William Penn) and James Logan, the provincial secretary of Pennsylvania who built Stenton as his home in 1730.

Be Part of the Solution

Become a Citizen member.Don’t be fooled by the skinny jeans and sneakers. The year is 1737, and these 10-year-olds are about to enact the Walking Purchase. “Okay everyone, on the count of three I want you to walk, steadily, in a straight line to that marker over there,” says the group’s tour guide. “Just wait one second.”

The guide then turns to the colonial group, and whispers, “Run as fast as you can.” They don’t need to be told twice.

As the colonialists quickly beat the Delaware Indians to the finish, the modern-day student reenactors learn an important lesson: History is not always fair. What was supposed to be an equitable demonstration of the boundaries of land sold by the Delaware Indians to the colonialists—listed in an agreement as the territory that a man could walk (not run) in a day and a half from a particular location—ended up as a one-sided race in which the British cheated their way into over one million additional acres, alienating their neighbors in the process.

Social Studies is the subject with the least emphasis in school these days, for one disheartening reason: Unlike math, reading and science, there is no standardized test for social studies.

This 18th century scene has been repeated every fall for the past 16 years by students participating in History Hunters, a unique experiential learning program that provides free workbooks, admission, and transportation for 4th and 5th grade Philadelphia School District students to five historic Germantown sites throughout the year. History Hunters was piloted in 2002 by the National Society of The Colonial Dames of America, who own and manage Stenton, with the support of local partners, including several foundations. Since then, over 15,000 students have experienced History Hunters.

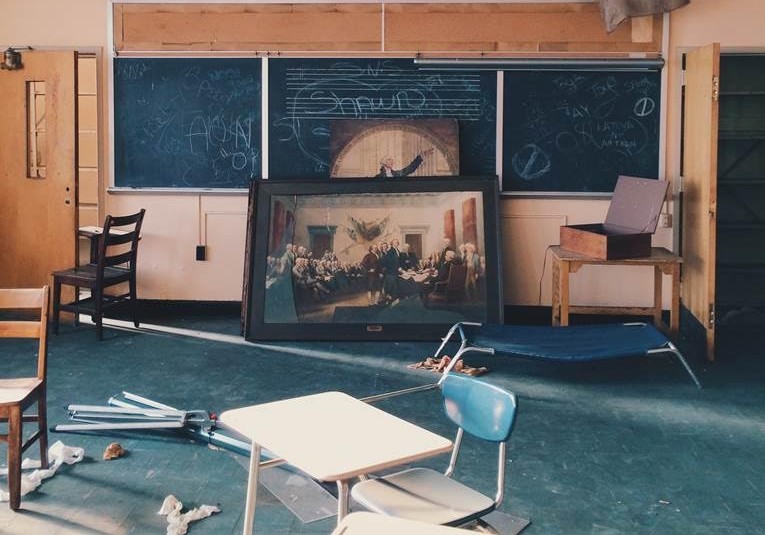

Each of the sites uses a different voice to tell the story of our collective American, and Philadelphian, history—a history that speaks to the issues we all face today. Stenton shares the experiences of the Native Americans; Cliveden, a Revolutionary War battle site, pins British sympathizers against patriots; La Salle University exposes students to artist Charles Wilson Peale, and how images can shape our understanding of history; Johnson House, a station on the Underground Railroad, delves into the hardships of slavery; and lastly, Wyck House explores Quaker values, including gender equality.

Social studies, it could be argued, is the most important of all subjects. It teaches students not just where they come from, but how their country came to be, what is required of good citizens, and how real change can come about through the efforts of a dedicated group of people. But it is, also, the subject with the least emphasis in school these days, for one disheartening reason: Unlike math, reading and science, there is no standardized test for social studies.

“The emphasis on test results makes social studies a stepchild, meaning that’s the area that is shortchanged if time runs short,” says Bonnie Shields, a retired Philadelphia School District reading specialist who now works as a History Hunters guide. “However I strongly feel understanding our past and how our country came to be, as well as how a democratic government works, is essential to understanding the responsibilities of citizenship.”

When social studies is taught in Philadelphia, it is usually from outdated textbooks that often fail to capture the imagination of students—both because the material can be dry, and because it is often one-sided. History Hunter organizers aim to present a more kaleidoscopic view of history that ensures each student can find his or her place in it.

Support the work of History Hunters.Do Something

The program is particularly devoted to sharing this perspective with students at schools that would otherwise lack the funding to go on field trips. Over 3,000 students participated in the program last year, many from schools with 92 percent economically disadvantaged population.

“History Hunters sees a largely African American population, and it is imperative that these students learn about history that is relative to them,” says Kaelyn Barr, the History Hunters program organizer and the director of education at Stenton. “[The program] teaches history on a more personal level, offering more personal stories of the individuals who lived right in our communities. History Hunters offers these stories from diverse perspectives, and challenges students to consider how they might respond under similar circumstances.”

About oft-overlooked Philadelphia history-makersRead More

In order to help teachers justify the addition of these field trips to their schedule, History Hunters ensures that standardized test subjects, such as language arts, are a part of each program. They distribute 100-page History Hunters workbooks at the beginning of the school year with texts, primary source materials, and writing assignments for each of the five sites. Over the course of the year, students will visit all five historic locations, exploring the themes that go with them in the days leading up to their trip. Afterwards, teachers often lead their students in projects that reflect what they learned.

Social Studies is the subject with the least emphasis in school these days, for one disheartening reason: Unlike math, reading and science, there is no standardized test for social studies.

Yet what students are most likely to remember are not the facsimilied pages from James Logan’s ledger, a 1772 guide to feeding and clothing slaves, or the entries from Deborah Logan’s diary that they find in the pages of their History Hunters workbooks. They will remember playing games brought over from West Africa by enslaved people, making an herbal eighteenth century recipe for cholic, trying on British army uniforms, and racing their classmates at Stenton in a greedy attempt to claim more land.

They will remember going to places in their own neighborhoods, that they would never otherwise visit, and seeing their shared history come to life.

Header Photo Via Historyhunters.org