to this story in CitizenCastListen

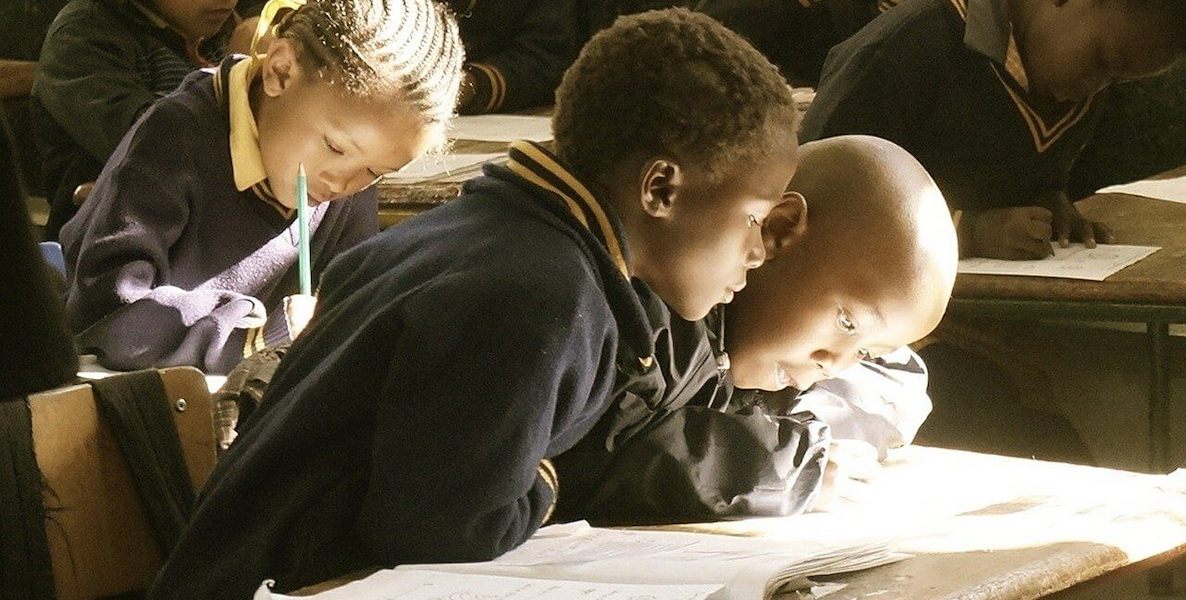

I work at Boys’ Latin, an all-boys charter school in Philadelphia, where virtually all the students come from marginalized communities in the nation’s poorest big city. My colleagues and I have been working with students and families on “Student Attendance Improvement Plans.”

Together, we’ve been able to improve 6th grade attendance from a little over 25 percent to above 95 percent, the highest rate for any grade in our school and nearly 56 percent better than district averages based on early data that shows just 61 percent of Philadelphia public school students are attending remote learning regularly.

So, how’d we do it? How did we get such incredible jumps in attendance?

First, we adopted the right mindset and approach.

- We didn’t focus on the attendance rate, but on our students and their families.

- Every time we reached out to students who were missing out on school, our goal was to understand what was happening—not what was wrong with them—in arriving at solutions together.

- We assumed every student wanted to come to school; in fact, we were sensitive to the fact that students could feel worse with every additional day they missed, concerned and increasingly anxious about not being able to catch up.

So, the first thing we made sure they knew was—not that they were missing out—but that they were missed. That their class wasn’t the same without them. That we wanted them back at school.

About ANEWLEARN MORE

And we assured them they would have help catching up. Their teachers and fellow students would be there for them. All of us had their back.

- We also assumed that families would appreciate our checking in on them. Which they did. They also didn’t want their children missing out on school.

For most, a single phone call was all they needed. During that call, we made a point to underscore why their child was missed at school, bringing up something positive they’ve done or something positive about them.

Second, in solving things together with our families, we found out that too often what was holding their child back from getting online with school were things out of their control. They hadn’t done anything wrong. Systems had failed them.

This is not about cultural competence training, nor anti-racist strategies, not even trauma-informed education. It’s just plain compassion, understanding and humanity.

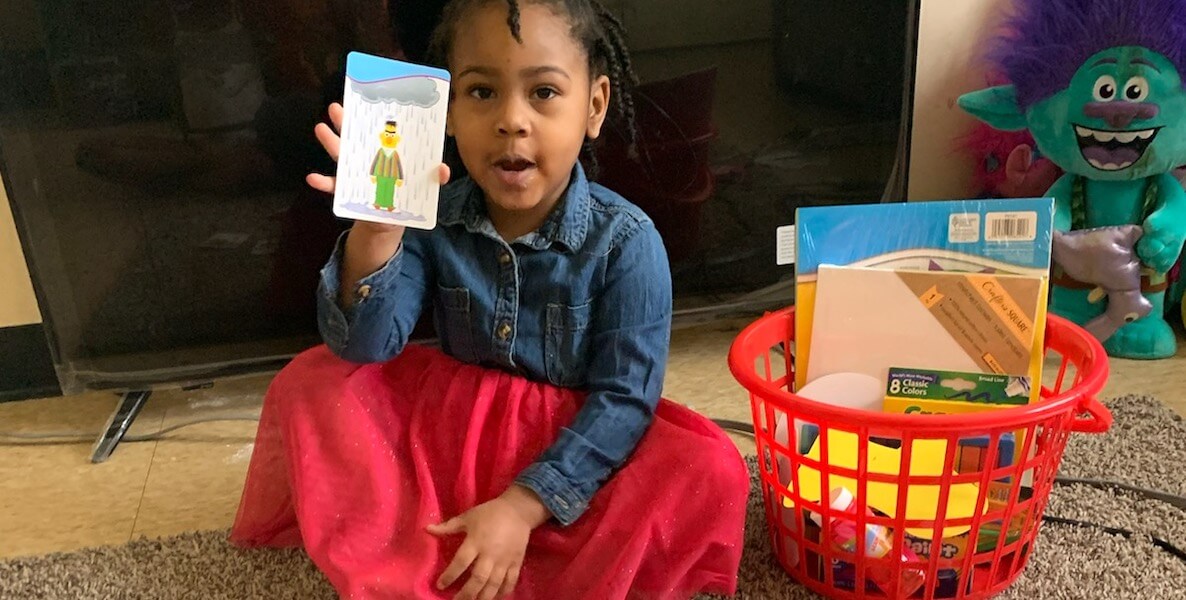

The social and economic fallout of Covid-19 has put schooling in chaos. Black and Brown families from marginalized communities don’t have disposable income to hire Zoom tutors or organize well-resourced pandemic pods. They don’t have the luxury of working from home while homeschooling their kids. They are left struggling the most to figure out, on-the-fly, how to keep their children learning.

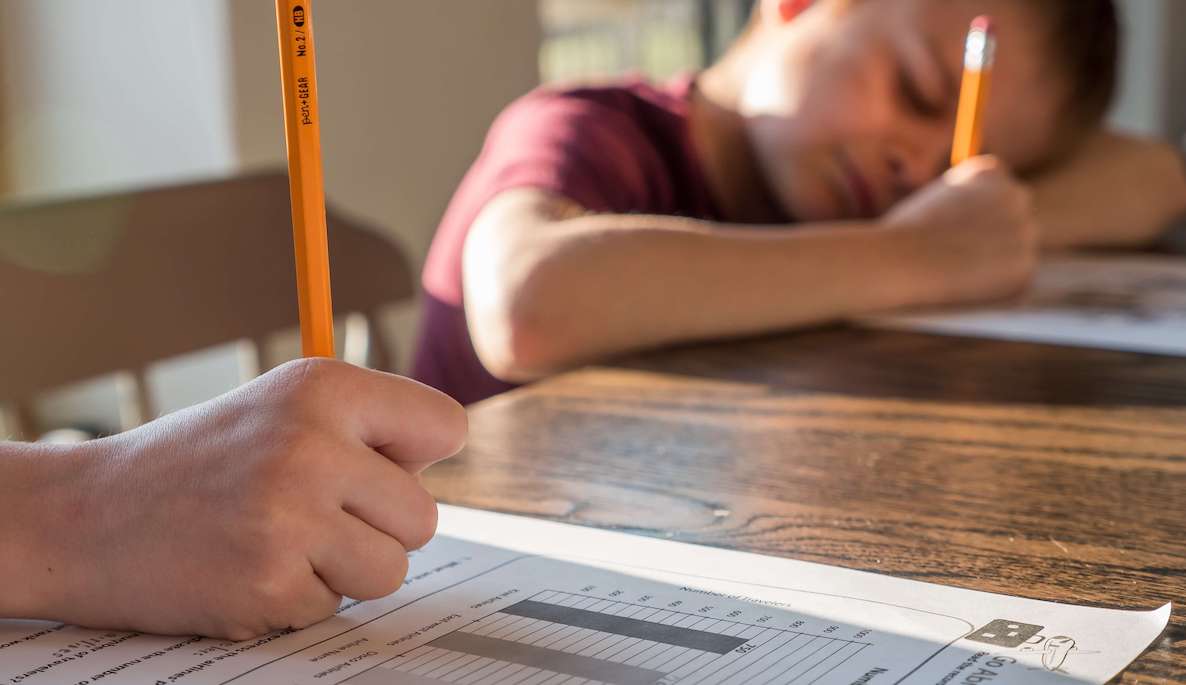

- Students may have gotten the much talked about Chromebooks, but that didn’t mean families had internet connectivity, let alone a desk or some other kind of set up for their child’s studies. Many of us spent our after-school and weekend hours helping families, not only set up their Wi-Fi, but also put together makeshift desks.

- Beyond material tools and digital access, we found so many students are struggling with basic computer skills. No one had ever taught them how to use Chromebooks, nor did many know how to type well enough to keep up with their virtual learning. What schools need to do (what we had to provide privately when we could) is a no-stigma introduction to and support of basic computer and typing skills.

- For students who didn’t have these kinds of material or technological challenges, but weren’t clicking into school because they lacked the motivation to attend, we worked together to address that.

We took the time to find out what their future plans were. How they saw themselves in five, 10, 15, more years. Then we worked backward to see how an education could help them get there.

Black and brown families from marginalized communities don’t have disposable income to hire Zoom tutors or organize well-resourced pandemic pods. They don’t have the luxury of working from home while homeschooling their kids. They are left struggling the most to figure out, on-the-fly, how to keep their children learning.

education during the pandemicRead More

As educators, we must always try to see where our students are. It’s the only way we can reach them and present mirrors of hope and a better future. This is not about cultural competence training, nor anti-racist strategies, not even trauma-informed education. It’s just plain compassion, understanding and humanity.

Kenneth Bourne II is a licensed Black male social worker and founder/CEO of ANEW, an organization committed to ensuring Black boys and young men have a fair shot at academic achievement and life success.

Image by ludi / Pixabay