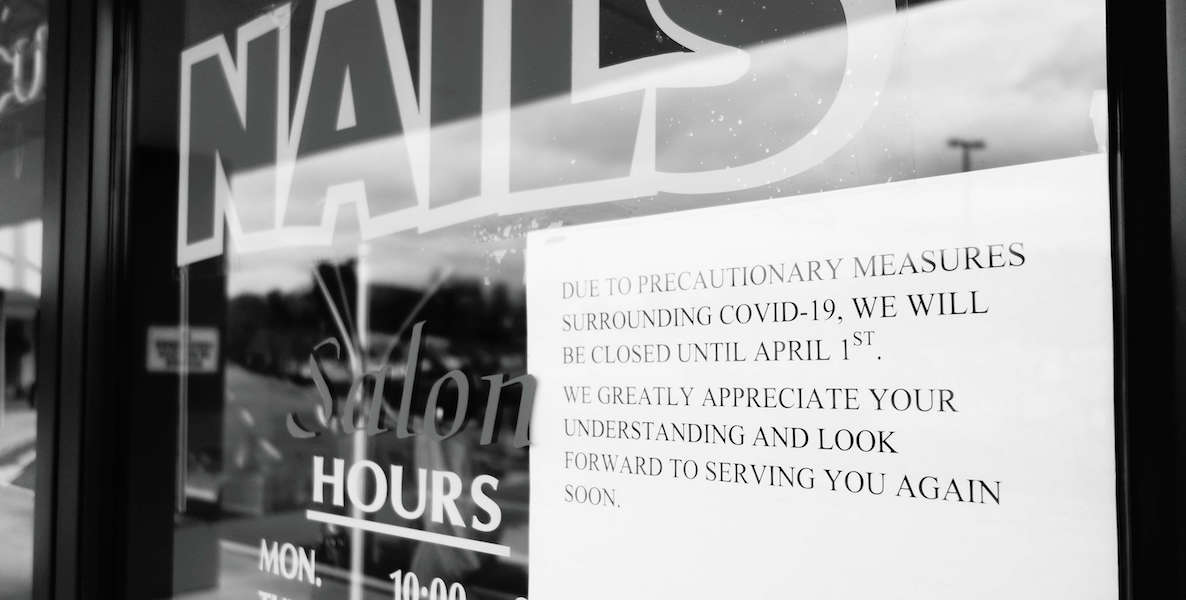

When the history of the pandemic is written, the federal government’s small business assistance programs will go down as one of its biggest policy failures.

In late March, Congress and the Treasury Department cobbled together a dizzying array of federal programs designed to help small businesses, notably the Payroll Protection Program (PPP).

I recently spent time working with a team of lawyers and financial experts, assisting small businesses in Philadelphia who were trying to get access to these loans and grants. Our work revealed several fundamental flaws with the program design.

First, creating a limited pool of funds is a terrible way to help the needy. It sets up a system of social Darwinism that rewards the strongest players.

![]() Many of our clients were childcare providers. Some of them had no accountants or formal payroll systems, so that they had a hard time understanding or providing the information and records that were required.

Many of our clients were childcare providers. Some of them had no accountants or formal payroll systems, so that they had a hard time understanding or providing the information and records that were required.

The result was that firms that had in-house expertise could quickly apply and others, including sole proprietors, were mostly left in the dust. By the time many of them got their paperwork together, the money had run out.

Second, definition of “small business” included firms with 500 employees and even more, because of the rules governing affiliations. So kudos to Shake Shack for returning their PPP loan—but they didn’t really do anything wrong. The program design allowed them (and thousands of big companies like them) to access the money.

Limiting assistance to businesses with fewer than 100 employees (or 50) would have been a better approach. So would a set-aside for really small businesses, preventing the large ones from gobbling up all of the money

Third, using banks to process applications is a terrible idea if you want to get money out quickly. The banks didn’t have the staff to handle this volume and they were quickly overwhelmed—again not their fault.

From day one there was a bottleneck that never went away. And understandably, banks wanted to deal with their customers first. So if a small business did not have a strong banking relationship, they had trouble even applying for funds.

Fourth, the PPP program has a built-in conflict between businesses and their ![]() employees. Businesses can get their PPP loans forgiven if they put their employees back on the payroll for eight weeks. But many employees would make more money by staying on unemployment, since Congress recently provided an extra $600 per week to unemployed workers.

employees. Businesses can get their PPP loans forgiven if they put their employees back on the payroll for eight weeks. But many employees would make more money by staying on unemployment, since Congress recently provided an extra $600 per week to unemployed workers.

We talked to many businesses who struggled to balance their desire to stay “open” with their conflicting desire to help their workers get more money.

The only good thing about these failures is that they have been so spectacular that they provide us with a clear opportunity to completely revamp the way we do this in the future. Fortunately there are some better ideas and models elsewhere.

![]() One model worth looking at is a work-sharing program used in several European countries, such as Germany. It allows companies to quickly tap government funds to keep workers on payroll during a downturn.

One model worth looking at is a work-sharing program used in several European countries, such as Germany. It allows companies to quickly tap government funds to keep workers on payroll during a downturn.

It’s not perfect, but it eliminates many of the flaws of the U.S. programs—it doesn’t depend on banks to get the money out and it coordinates business assistance with the unemployment compensation system.

If Congress provides another wave of funding later this spring, they should address the flaws in the PPP program and create assistance that works for all small businesses.

Photo courtesy Eden, Janine and Jim Flickr