Even though traditionalists may warn that we’ll rue the day if state courts are injected into an active role of making education policy, given a Pennsylvania public education system beset by inequity and gridlock, a recent development in the Commonwealth Court should be seen as a ray of hope by those looking for positive changes.

A few weeks ago a Commonwealth Court judge finally set a trial date for a slow-moving lawsuit on education funding, and when she did so she also shone a light on a state legislature and governor who are at loggerheads on how to fix the broken system that pays for our schools.

The vaunted “fair funding formula” that was adopted by the Republican legislature in 2016 and signed by Democratic Governor Tom Wolf has now broken down over a “hold harmless” clause that some electeds are using to subvert the once promising formula because it hurts some newly acquired constituencies plagued by declining enrollments.

MORE ON EDUCATION IN PA

Forty years ago, rural Pennsylvania was represented by a balanced mix of Democrats and Republicans, while GOP legislators almost exclusively represented the well-off “country club” school districts of suburban Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. Today this is hardly the case.

Some of the state’s poorest school districts are found in the solidly Republican northern tier along the New York border, and the once Democratic southwest has flipped to solid Republican with the Trump vote in 2016 and 2020. The GOP, which now features a Senate Majority Leader from Westmoreland County, has swapped eastern suburbs for western Rust Belt counties, places that have been losing jobs and population for decades and have the underfunded schools to show for it.

It so happens that a funding formula declared “fair” because it emphasizes a district’s actual per student costs also has a sting in it because it hits you for having declining enrollments. That’s where the “hold harmless” clause comes in—it guarantees a district its historically highest state appropriation based on long-gone phantom students, and it does this by shutting the valve on the total amount of money that flows through the fair funding formula.

If demography is destiny, the Republicans are reckoning with the fact that in recent election cycles they’ve lost seats to the Democrats in the populous and growing southeast while maintaining their hold in most of the ascendent south-central. But in total, it is in this singular Pennsylvania growth region, south and east of the Allegheny Mountains and comprised of some 15 counties, where 55 percent of all the public school students in the state are now located and likely to keep expanding.

And so it is that while the Republicans take up the cause of “hold harmless,” it is Democratic Governor Wolf who is still championing the fair-funding formula he signed five years ago. And while the Republicans have been persistent in filing objections and slowing down the Commonwealth Court lawsuit, Wolf has taken a hands-off approach.

Originally filed in 2014 by urban and rural school districts impacted by poverty and low value properties, the suit crossed an important milestone in Commonwealth Court when presiding Judge Renee Cohn Jubelirer swept aside the last remaining preliminary objection and set a tentative trial date of September 9, with a pretrial conference scheduled for May 20.

Though it’s no small thing, during the past seven years the one thing the petitioners have ever wanted is their day in court. And a “trial on the merits” is exactly what the state Supreme Court had awarded them in a 2017 decision by Justice David Wecht, who remanded the case that’s now moving towards trial.

In his order, Wecht teed-up the current case so that it is destined to reinterpret the state Constitution’s education clause as guaranteeing a “fundamental right to an education” and beyond that to “a constitutionally adequate education” that produces citizens who can function in a modern economy.

The chief ill of the property tax, though, is that it is another form of gerrymandering, a misuse of government power to design a constituency for the benefit of the few. It is not the levy itself, but its narrow and exclusive application that makes it a frequently misused tax.

Attorneys for both the Public Interest Law Center of Philadelphia [PILCOP], and the Education Law Center [ELC], who filed the original lawsuit in 2014, celebrated the recent Commonwealth Court decision.

“Trial is coming soon,” said PILCOP attorney, Mike Churchill, “and the General Assembly will no longer be able to continue ignoring their responsibility for public education.”

The objection dismissed by Judge Cohn Jubelirer had come from lawyers for the top Republican leader in the Pennsylvania Senate, President Pro Tempore Jake Corman, who attempted to block the testimony of two mothers, from Wilkes Barre and Philadelphia, because their kids named in the suit have since graduated.

But Judge Cohn Jubelirer ruled that because the lawsuit focuses on the sharp disparities of wealth and poverty among Pennsylvania schools, the mere technical fact their kids have aged out of the school system did not refute the “great public importance” of the parents’ testimony.

For more than 30 years the Republican gospel in Harrisburg has been to limit the growth of state spending on education and, whenever possible, to actually cut it. Since the GOP has held sway in at least one or more of the House, Senate or Governor’s offices during that time, the key feature of education funding in Pennsylvania has been the overall relative decline of state spending in education and the consequent rise of local spending.

Pennsylvania’s annual state-appropriated share of school funding—once 50 percent back in the 1970’s—has steadily fallen to 38 percent, while the availability of local tax resources has become the make or break factor for all our schools.

If fixing our broken education system is in part a question of more money, what kind of money are we talking about and what can a court actually do to make a legislature spend more?

First, as to the size of the problem, a 2006 study by the state Board of Education found the state’s K-12 schools overall were underfunded by $4 billion. (The state’s most recent spending on K-12 schools is some $9 billion.)

Second, as to leveraging increases in state spending, where courts can play a role is by measuring the education promises and purposes of the state Constitution with the actual results on the ground and by forcing the issue where the law is not being met.

To date, Judge Cohn Jubelirer (she ran for office in 2011 as a Republican, and is on the ballot this November for retention) has presided over a pretrial process that has closely hewed to the format of the Democratic Supreme Court’s 2017 remand decision, which emphasized the point that the petitioners are asking the Commonwealth Court to grant them “continuing jurisdiction.”

It would be most telling if she decides to grant this request, for it means the court would maintain surveillance over the case and would be on permanent standby to address the petitioners’ concerns within a wide scope of the Legislature’s decision making process in funding schools.

If such continuing jurisdiction is declared by the court, it’s possible that more than a few legislators of both parties will view it as an intervention in the legislative process and some may make strenuous objections.

But the prospect of subpoenas for legislative witnesses and information have already been slugged out in the pretrial motions. The Republican caucus leaders have already won exclusions both for themselves and for certain kinds of information under the speech and debate clause.

Continuing jurisdiction, therefore, while a new and thorny reality in Harrisburg may also come with a beneficial upside. What will happen, for example, if the court focuses on the property tax in the manner that the petitioners have requested?

On the point of the state’s hybrid—mixed state and local—funding of schools, Judge Wecht in his 2017 opinion chose to emphasize the petitioner’s contention “… that many methodologies exist that would support the state’s interest in preserving local control of education without compromising the ability of students in low wealth districts to obtain an adequate education…” [but] “… the General Assembly has irrationally enacted a law that benefits a select few…”

With regard to the presumed benefits of levying local taxes and wielding local control of schools, Judge Wecht called it “… a cruel illusion for the poor districts due to the limitations placed upon them by the system itself.”

Court decisions could ultimately lead to the reshaping of funding policies so per student aid grows and growing districts get more per student. We could get positive change where we now have only partisan and parochial obduracy.

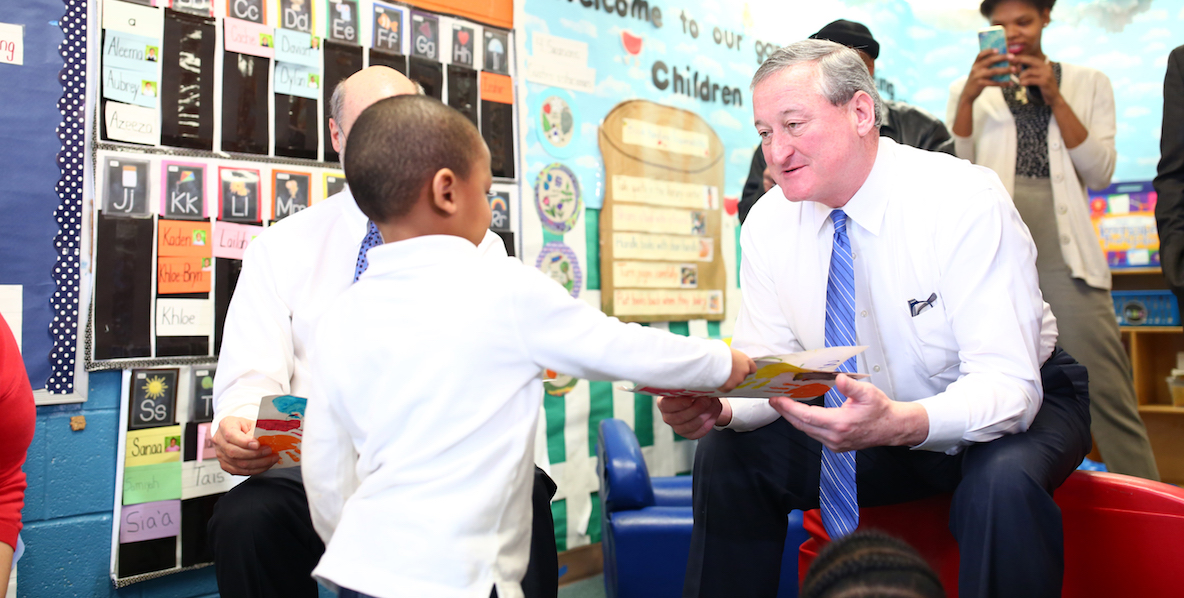

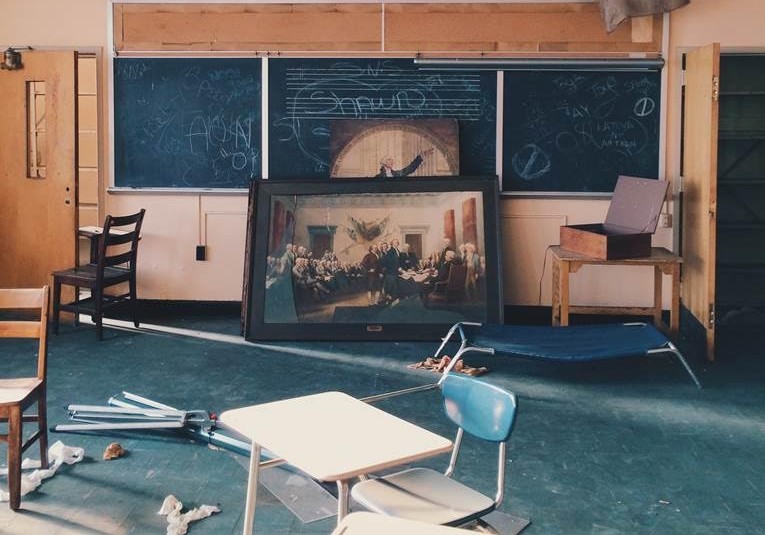

As matters stand, affluent districts, because of the high wealth of their local tax base, are able to spend as much as three times more per student with only minimal reliance on state funding. These are the schools that on opening day are passing out free laptops, while poorer districts have done away with libraries and guidance counselors.

For decades, state legislators have thrown themselves against the chimerical evils of the property tax like a cavalry charge of old. Once the baby boomers had gotten their kids out of the school system, they turned on the property tax as though it was intended to drive them to ruin. Over the years, legislators have tried to patch up the property tax with goodies and fixes, enacting homestead exemptions and reimbursements from gambling proceeds, for example.

More pointed complaints about the property tax tie it to the credible charge that it is the mechanism that make a kid’s zip code the true measure of the education they will receive.

By contrast, more sober comments have come from school district business administrators and academics in public administration who have praised the property tax as a stable and reliable revenue source.

The chief ill of the property tax, though, is that it is another form of gerrymandering, a misuse of government power to design a constituency for the benefit of the few. It is not the levy itself, but its narrow and exclusive application that makes it a frequently misused tax.

So what would happen if a court, seeing denial of equal protection of the law, would propose a reexamination and recasting of the property tax so as to cure its bias by widening its geographic catchment area, broadening its constituency, and sharing the revenue?

Court decisions could ultimately lead to the reshaping of funding policies so per student aid grows and growing districts get more per student. We could get positive change where we now have only partisan and parochial obduracy.

Looking ahead we know some things for sure: A few months from now the two mothers from Wilkes-Barre and Philadelphia will finally get to tell the story about the adverse conditions in the schools their kids went to and to do so in a Court of Law equally endowed like the legislative and the executive with the power to right wrongs.

Want to make sure our elected leaders are making smart decisions about education in Pennsylvania? Vote in the upcoming PA primary

- Our voter guide lays out everyone who’s running for office and more

- Here you can learn about all the judges who will be on Philly ballots

- Have questions about voting? Find answers in our PA voting FAQ.

- Make sure you’re registered, apply for a mail-in ballot and more

Charlie Bacas spent 20 years in the state government, including in the Governor’s Office of Bob Casey and as chief of staff to House Majority Leader Jim Manderino. He lives in York, PA, where among civic positions he’s served as Redevelopment Authority chairman.

Photo by Ivan Aleksic on Unsplash