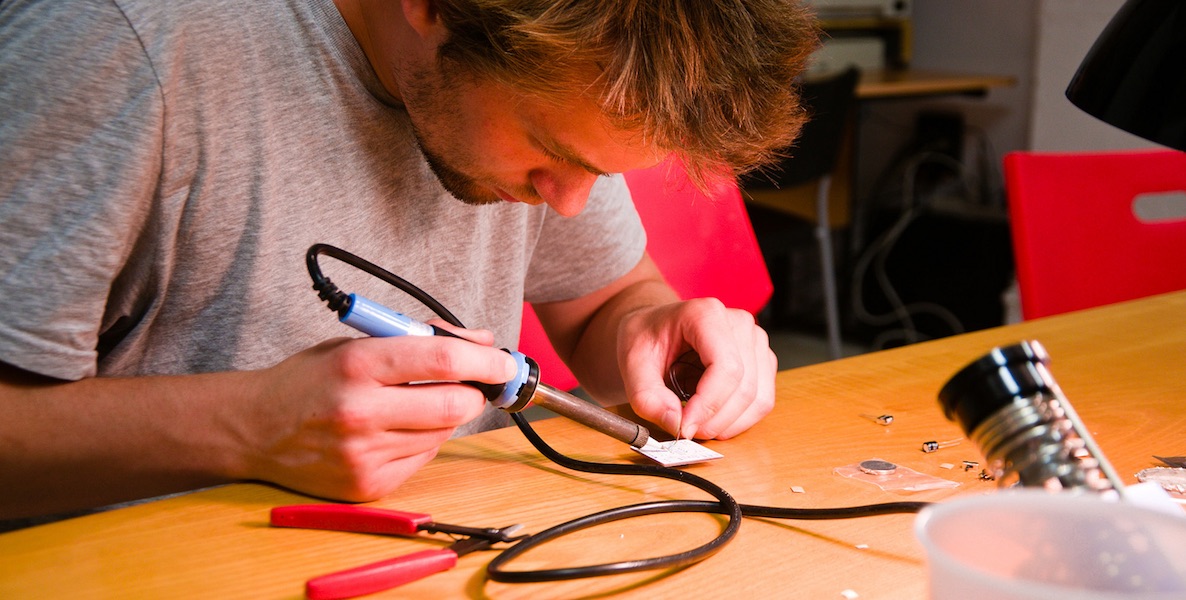

Walk into a first floor studio of the newly reimagined Bok Building any night of the week, and you’ll find yourself among Philadelphian manufacturers hard at work: Making a 14-foot “Connect Four” set that can be played with a Dance Dance Revolution pad, turning a 1930s radio the size of a dresser drawer into a karaoke machine, repurposing old newspaper boxes into instantaneous printshops, or just tinkering with a wide array of electrical parts and equipment on hand.

This is Hive76, a DIY maker space that opened in the shuttered Bok school building, near East Passyunk, a few weeks ago. Like other maker spaces in the city—including The Hacktory and The Department of Making and Doing, from which it split in 2009—Hive76 captures two ideas of working that have grown around the country: A return to (at least small scale) local manufacturing, and co-working spaces, with all the inherent collaboration that goes with them.

“It’s good to keep the door open,” says Hive76 president Chris Terrell. “You never know when someone who has totally different experiences than you is going to walk by and solve your problem.”

This is the essence of how maker spaces work: People with a drive to create anything in fields as varied as fine art to technology to bioengineering come together to share tools, ideas, and a common creative environment. It is a modern and collective riff on what people have been doing for centuries by themselves in basements and spare rooms and on top of kitchen tables after dinner—tinkering. What could we create if we tinkered together? asks the maker movement.

The maker industry has potential to create jobs, bring people to the city, and support local businesses. This is what has happened in Pittsburgh which, the National League of Cities noted, has become a dark horse hub of innovation in recent years.

The answer could be: A better city. According to a National League of Cities report issued last week, an estimated 35 million adults in the United States are makers, and 26 percent of cities—and growing—have shared maker spaces, like Hive76. And they are increasingly manufacturing things that people want to buy. From 2011 to 2012 alone, sales of locally-crafted products around the country, like wood crafts and leather goods, grew 29 percent; by 2017, the market is expected to be as high as $6 billion.

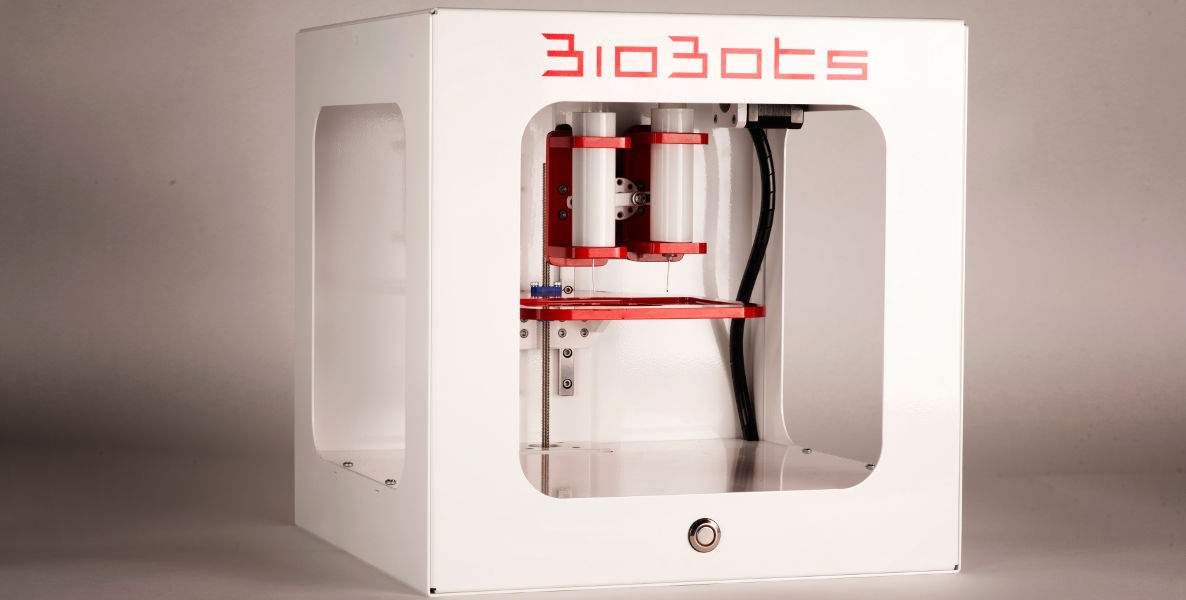

In cities like Philadelphia, where big manufacturing has taken a nose dive, small makers—crafts people and artists and tech nerds who create products from their own homes or in maker spaces—are unexpectedly taking its place. The maker industry has potential to create jobs, bring people to the city, and support local businesses. This is what has happened in Pittsburgh which, the National League of Cities noted, has become a dark horse hub of innovation in recent years. In Philadelphia, BioBots, a 3D medical tissue printing company, was devised in a Penn dorm room—but the founders made the first prototypes at NextFab, another Philly maker space close to Hive76. They went on to get more than $200,000 in investments, and are now on their second model.

“The maker movement has such great potential to alter the fabric of business and manufacturing in cities,” says Brooks Rainwater, co-author of the National League of Cities report. “The city itself is the place where the maker movement lives, breathes and succeeds. What you have here is the ability to localize the manufacturing of goods for people in that local area.”

Hive76 takes the community aspect of maker spaces a step further with a membership model in which members own and operate the organization, paying dues and meeting regularly to make decisions together about everything from whether to collaborate with the Delaware Center of Contemporary Art, to which new members to accept. Criteria for membership include agreeing to care for the space and its members and articulating what the member hopes to receive and give to the space—as well as a desire to better Philadelphia through their collective efforts.

The collective started with just a handful of members, but now has about 30, who come from all parts of the city and suburbs, and several different fields, though fine arts and engineering are the most common. Terrell went to school for printmaking and bookbinding at University of the Arts, but sought out Hive76 because he wanted to learn how to do 3D printing. His current project is repurposing old metal newspaper dispenser boxes by putting wireless printers inside them that can print a publication on the spot whenever a box is opened. He plans on using these to raise awareness about the maker movement, and profile the work of innovative Philadelphia artists and makers.

“The maker movement has such great potential to alter the fabric of business and manufacturing in cities,” says Brooks Rainwater, co-author of the National League of Cities report. “The city itself is the place where the maker movement lives, breathes and succeeds. What you have here is the ability to localize the manufacturing of goods for people in that local area.”

Other Hive members have come to the maker space for skills that have changed their career trajectories or helped their careers explode. Member Chris Thompson also has a fine art background, but using skills he learned at Hive76, he’s now teaching laser cutting and 3D printing at Philadelphia University. Jordan Miller, a biomedical researcher at Penn, developed a 3D printer at Hive76 that could print sugar; his invention, like BioBots’, could also print the vasculature of different human organs, leading to the ability to grow new organs outside a human body, an important contribution to bioengineering research.

“We keep the doors open for ourselves, but other people just come in and we help them,” says Terrell. “Students working on projects will come in and be stumped with their work, and people just volunteer their help, without asking ‘what’s in this for me?’”

This kind of democratic distribution of technical and artistic knowledge at free or low cost is what renders maker spaces unique and makes them poised possibly to change our city’s relationship to innovation education and small-scale production. Community-run maker spaces might also be a valuable bridge to help open engineering and tech innovation to groups that have been historically underrepresented in those fields, including women. Leslie Birch is a writer and web content producer, and one of six female members at Hive76. She joined because she needed access to more tools and people who knew how to work the equipment she wanted to learn about and lacked entree into the male-dominated world of tech.

“At the tech conference I just went to of maybe ten thousand attendees, more than three quarters were men,” says Birch. “Men can get really defensive in tech and it can be intimidating. But not at Hive76. They welcome women. If you are bold enough to walk in the door, you are sure to get support and help for your project.”

When she did walk through the door, she said she found a great community synergy. “The guys already there had the tools and the knowledge, but they needed good ideas. I brought a great idea and an artist’s vision and they helped me get going right away.”

“We can do things that we could never pull off working alone,” Terrell agrees. “To do something great, you have to work together.”

Header Photo: Flickr/Mitch Altman

Like what you’re reading? Stay updated on all our coverage. Here’s how: