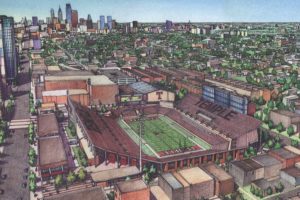

Since we’re on the subject of the Philadelphia Eagles’ magnificent Super Bowl win on Sunday, maybe now’s the time to ask them if they could do North Philly a favor: Keeping Temple University from building that monstrosity of a football stadium on Broad Street.

After all, the Eagles have built its Cinderella brand all season on the strength of being the most “socially conscious” team in the National Football League (for whatever that’s worth). So, this would be a good time for the Eagles organization to look deep within its corporate soul and find us beleaguered North Philadelphians—current and ex-pat—a solution to the football stadium crisis brewing in our backyards.

Temple, with its insatiable gentrifying appetite, has greedily consumed the North section of Philly for years, increasingly expanding its footprint in a bid to become the world’s largest urban university. Not to knock it too much—that’s actually fine. In a way, why not? So much of North Philly is old, crumbling and dejected into sunken house disrepair that folks who grew up there should be honest with themselves. Who wouldn’t want to flip it? And what city government wouldn’t want a generously-funded public university to help gut, clean and renovate the notoriously distressed section?

At issue is the way Temple pursues that dream, forcing long-time residents out along the way and creating rippling scenarios of mass displacement. Studies already suggest a direct correlation between aggressive gentrification and aggravated low-income outcomes. As shown by Hidden City Philadelphia’s David Hilbert, there has already been a 19 percent decrease in black North Central Philly residents—leading to the growth of whiter residents and mostly white Temple students.

A 12 percent decline in certain black residential tracts between 2000 and 2014, according to Hilbert, translated into those residents “mov[ing] into more middle-income black neighborhoods like Wynnefield and Overbrook, while others relocated into pockets of new poverty in the lower Northeast. Many left the city altogether.” While the top of Hilbert’s last sentence there attempts to put a positive spin on it, we can’t ignore the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia’s observation that more than 20 percent of vulnerable Philly residents who are pushed from one neighborhood to another end up in an even worse, much more distressed hood.

Learn more about the stadium, share your thoughtsDo Something

While, yes, Temple is—as Fed Philly notes—an “anchor institution,” we still have to ask who that helps. And if the current rate of Temple expansion is already displacing a disturbingly high number of residents, while creating a nuisance that its bullshit Good Neighbor Initiative doesn’t solve, then we can only assume a football stadium in the middle of North Philly won’t make it any better.

Temple’s Owls continuing to play at the home of the, now, legendary Super Bowl champs who valiantly slayed the pro-Trump Goliath would be a better option. It’s way better than the high displacement, environmental impact, massive traffic jams and logistical headaches that would cause for North Philly. Broad Street, at least during college football seasons, would be an unusable mess.

On the other hand, the Linc is the stadium that housed the Eagles’ remarkable playoff run; it is the home of a team that is now nationally beloved for its DeBrady-fication skills. One has to ask why it’s absolutely necessary for the Eagles to now double their rent. Probably just good old-fashioned capitalism, despite the social movement name the team has built for itself; it’s just time to capitalize on #FlyEaglesFly.

For whatever reason, the Eagles are mugging Temple for an extra $1 million a year to lease the Linc, in addition to a $12 million deposit. Shows how much the Eagles care about higher education, huh? Even Mayor Kenney blasted Eagles ownership for the move last year for the sudden slumlord move. But with City Hall caught up in Super Bowl euphoria and the money grab that comes from anticipated visibility and tourism, don’t expect any follow up on that. The Eagles are in a position to get anything they want from the city.

College football programs, according to many recent studies, are proven fiscal black holes for everyone involved, especially students and families who end up paying for them through spiked costs and fees. Has Temple figured out a way to pay for that $130 million, easily-overrunnable project other than borrowing off bonds and increasing tuition?

But the economics of a Temple-owned stadium makes little sense in terms of the return on investment. For one, Temple risks continually pissing off its humble neighbors and there’s no indication the university has concocted a grand plan to repair institutional-residential relations. They figure all they need is the backing of local politicians, including those—like Kenney—who’ll they’ll expect to back off considering the Eagles’ Super Bowl win.

And it’s not like City Council President Darrell Clarke, who represents Temple’s district, is going to do anything about it since he appears fairly beholden to powerful university interests. “It’s Temple’s responsibility to get the community on board. It’s not my responsibility,” Clarke reportedly shrugged. “It’s my responsibility if the community decides it’s interested in having a stadium to work out whatever issues remain.” But what about if a large and active portion of the community is, ummm, deciding that it’s not interested?

From Charles D. EllisonRead More

An SB Nation study of the seven cities where college and professional teams share stadiums shows that, for the most part (with the Patriots’ Gillette stadium being the exception), it works. In fact, the Owls-Eagles collaboration was highlighted as the most ideal of college-pro arrangements, with SB’s John McWinnie noting that “Temple and the Eagles have been tied at the hip since 1978, and for the relationship to last this long, the Owls must be benefiting from using the Eagles’ facilities.”

Honestly, who really wins with a new football stadium? Is it all cosmetic, just to see more red and white light poles and buildings along Broad Street? The better, least costly and more peace-of-mind option is to simply keep the Owls at the Linc. So why are influencers on both sides trying to mess that up and, in the end, ruin it for the average folks and fans in the middle of it?

Charles D. Ellison is Executive Producer and Host of “Reality Check,” which airs Monday-Thursday, 4-7 p.m. on WURD Radio (96.1FM/900AM). Check out The Citizen’s weekly segment on his show every Tuesday at 6 p.m. Ellison is also Principal of B|E Strategy, the Washington Correspondent for The Philadelphia Tribune and Contributing Politics Editor to TheRoot.com. Catch him if you can @ellisonreport on Twitter.

Photo: William F. Yurasko via Flickr