There was an unintentionally revealing moment last March when Jim Kenney was being interviewed by Matt O’Donnell on Channel 6’s public affairs show, Inside Story. O’Donnell had noted that Kenney inherited a budget of roughly $4 billion, and was now presiding over one of $4.7 billion—a 17 percent increase in three short years, seven times the rate of inflation. O’Donnell, wondering if the city had a spending—and not a revenue—problem, asked whether it would be possible to “cut wasteful municipal jobs.”

“What does that mean?” Kenney said, pouncing. “What does ‘cut wasteful jobs’ mean? I don’t know what that means.”

It was a revealing moment, in that it not only exposed the Mayor’s big spending predilections, but also showed him to be a lifelong product of sprawling, unaccountable government. Only someone long trapped inside the trappings of bureaucracy would reflexively dismiss the notion that a government’s fiscal engine might not be running at peak efficiency.

Fact is, Jim Kenney now has a $4.7 billion budget and a $3 billion schools budget. If, as he suggests, his government were running at peak efficiency, how is it that nearly $8 billion is not enough to service 1.4 million residents?

Well, recent headlines have answered Kenney’s challenge to O’Donnell by identifying the waste. There have been ample examples of late illustrating just how inefficient and wasteful Jim Kenney’s government is. Charles Ellison covered many of them for The Citizen here, and an Inquirer editorial laid out the disturbing trend here.

The case studies run the gamut from the unreconciled city bank accounts, $924 million in accounting errors and missing $33 million (the Kenney administration’s sleuthing to find the money is reminiscent of O.J.’s tireless efforts to find the real killer), to the $50 million boondoggle over a new police headquarters, to the fact that the city overshot its overtime budget this year by a mere $40 million.

Fact is, Jim Kenney now has a $4.7 billion budget and a $3 billion schools budget. If, as he suggests, his government were running at peak efficiency, how is it that nearly $8 billion is not enough to service 1.4 million residents? Supply-side economics may have since been discredited, but that doesn’t mean Ronald Reagan was wrong when he said, “We could say the government spends like drunken sailors, but that would be unfair to drunken sailors, because the sailors are spending their own money.”

Share your thoughts with your electedsDo Something

Councilman Alan Domb, whose cross-examining of the city’s Director of Finance Rob Dubow and Treasurer Rasheia Johnson last April first uncovered the city’s systemic accounting woes, recently asked his staff to dive into just where the city’s recent spending splurge has gone. Kenney has added $709,702 million in new spending since taking over from Michael Nutter in 2016. Of that, an astounding 60 percent — $425,806 million — is tied up in city worker salaries, benefits and labor costs. Kenney has gone beyond just feeding the beast, in other words; the beast is eating the budget.

“We have a spending problem,” Domb explains. “It’s very telling. For every $1 you increase salaries, health and pension costs go up by about $1, too.” And keep in mind that our unfunded pension liability currently eats up roughly 16 percent of the budget — and the administration’s plan to get the fund to 80 percent funded by 2029 is full of rosy-scenario assumptions — like the lie that we’ll see just shy of an 8 percent rate of return.

Domb says inefficiencies abound in just about every city department. Take the prisons, he says. We’ve laudably cut the number of those incarcerated from 8,300 three years ago to 5,300 today, but have only reduced the prisons budget by 2.5 percent. “Don’t tell me you need the same number of guards when you’ve taken 3,100 people out of the prison population,” he says. “If you cut the prisons budget by 15 percent, you could save $60 million a year. Over time, that’s a good chunk of the spending on salaries these last three years.”

“We’re like the guy in the car, looking in his rear-view mirror and marveling at how far he’s come,” Levy says. “Meantime, he’s not looking out his side window, where all these other cities are passing him by.”

Domb is quick to emphasize that our problems are mostly systemic, and not necessarily the product of any one mayor’s fiscal irresponsibility. “The crux of our problem is that we have a 26 percent poverty rate and another 31 percent that don’t pay taxes — the nonprofit eds and meds,” Domb says. “That leaves 44 percent of our population that pays all the taxes. We’ve got to figure out ways to grow that 44 percent tax-paying base, instead of just taxing them more to spend more.”

That’s why it’s imperative to figure out what our return on our taxpayer investment has been. Yes, Kenney has spent like a drunken sailor—but has said spending grown the local tax base?

Turns out, there are some indications that the city has added a sprinkling of jobs the last two years, thanks in large measure to the national economic boom that has been fueled at least in part by the Trump tax cuts. In its 1,000 day report released last week, the Kenney administration heralds that working city residents rose to 660,000 last year from 646,000 in 2015. That would amount to a 2.2 percent rise that beats out Baltimore and Pittsburgh, among other cities.

Articles from Larry PlattRead More

Problem is, Bureau of Labor Statistics Area Unemployment Statistics (LAUS) don’t always accurately tell a city’s economic development story because they report by “place of residence” — and not by where the jobs actually are. In other words, a hypothetical bedroom community could have 0 percent unemployment and 100,000 working residents but no jobs at all if everyone works at a plant the next town over. In our case, given that roughly 40 percent of Philadelphia’s “working residents” reverse commute to the suburbs, LAUS statistics don’t accurately capture the city’s economic growth.

That said, the report is right that we are doing a bit better of late. Comparing Bureau of Labor Statistics one-year rolling averages (September 2016-August 2017 compared to September 2017-August 2018), we’ve added 12,000 jobs for a growth rate of 2 percent. That’s above our post-recession average of 1.4 percent annual growth and the national average of 1.7 percent.

That’s a good thing, but let’s keep the corks in those champagne bottles. The gains are nowhere near where they need to be to justify our current ballooning of city spending. Roughly half of the jobs we’ve added have been in the aforementioned tax exempt eds and meds sector, and a sizable number have been low-wage jobs. Moreover, we’re still trailing too many peer cities in terms of economic growth. Paul Levy, President and CEO of the Center City District and our foremost guru of growth, calls these baby steps “Philly-style growth. We beat Memphis and Baltimore. Yippee.”

About Mayor Kenney and taxesRead Even More

Since the great recession, Philadelphia’s annual rate of growth — 1.4 percent — ranks 24th out of the nation’s top 25 cities. As Levy points out, had we grown at the rate of the average city during that time, we would have already added the equivalent of an Amazon workforce to our economy. Levy points out that cities with higher rates of job growth tend to have lower rates of poverty, which is why he ties his tax reform plan — raising commercial real estate taxes in order to cut the wage and Business Income and Receipts taxes — to attacking poverty. The best way to address poverty is to grow the tax base, rather than just continually redistribute what you already have.

Instead, Levy says, we’re stuck. “We’re like the guy in the car, looking in his rear-view mirror and marveling at how far he’s come,” he says. “Meantime, he’s not looking out his side window, where all these other cities are passing him by.”

Last week, Mayor Kenney did something truly innovative when he declared a disaster in opioid-plagued Kensington and created an on-the-ground emergency operations center to break down bureaucratic roadblocks in getting services to those most in need. “Enough is enough,” he tweeted. “What’s going on in Kensington isn’t acceptable.”

It’s that kind of leadership we need on addressing poverty by way of economic growth. The first step to becoming that kind of visionary leader will require the mayor to make sure that what he spends gets us what we need.

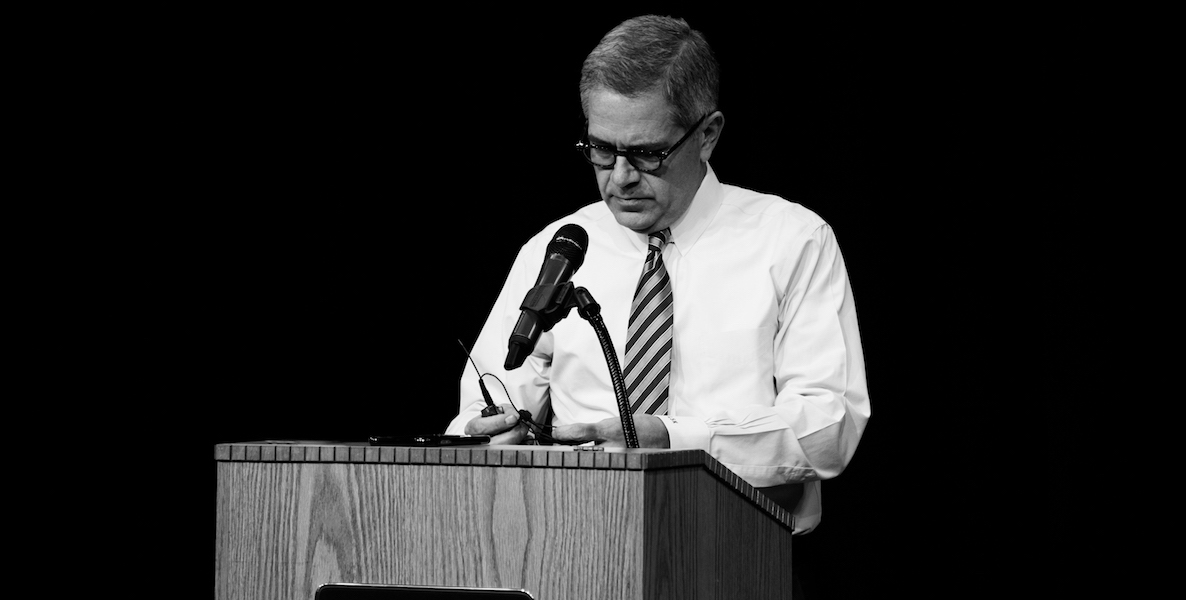

Header photo courtesy of Jared Piper for Philadelphia City Council / Flickr