Reading newspaper headlines and op-ed columns regarding the upcoming presidential election is a dreadful exercise. It is becoming clear that the unthinking extremism that increasingly defines American politics is now threatening more than dysfunctional government; it has begun threatening violence.

The nominal cause of this threat is President Trump’s uniquely destructive idiocy—namely, his comments sowing doubt as to whether he will accept the upcoming presidential election results.

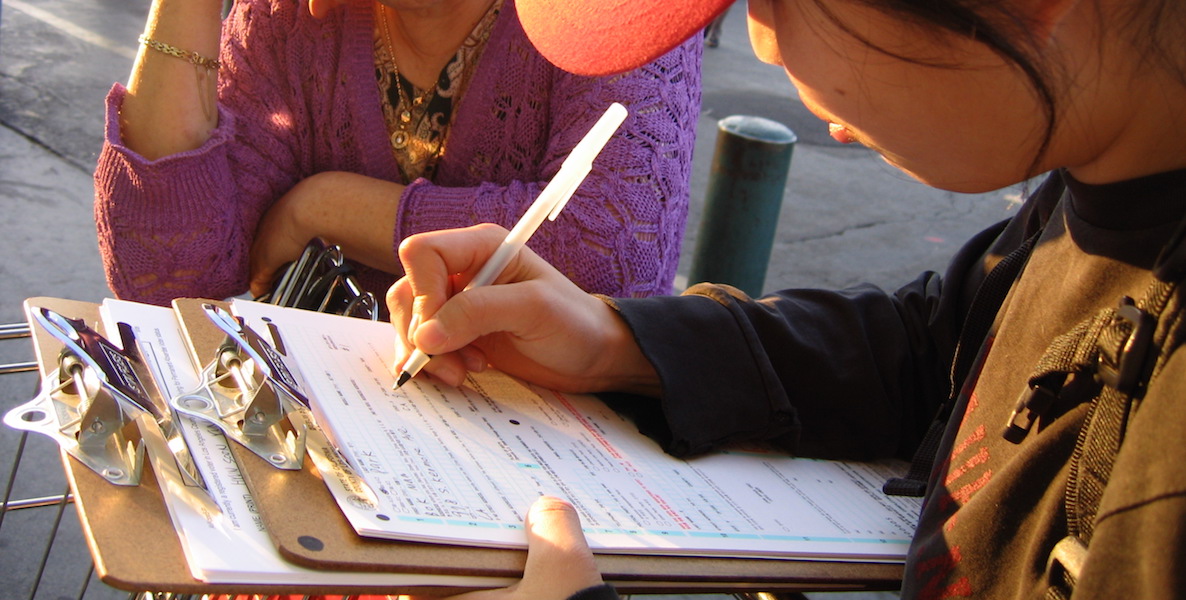

Vote and Get Out The VoteDo Something

This is not to say that a coup or civil war is on the horizon, but refusing to acknowledge that, as things stand now, the 2020 election will leave some Americans dead and deposit a dark blot on our nation’s political history is wishful thinking at best and irresponsible at worst.

As is the case all too often with the president, though, Mr. Trump is not necessarily the problem when it comes to our slowly burgeoning electoral dispute, but rather serves as the ugly, buffoon-like, bloviating manifestation of a much larger, deeper, more serious problem. And that problem, in the present case of potentially contested election results, is that we are no longer a people fit for self-government.

As reported by Persuasion’s Yascha Mounk in The Atlantic, a recent poll released by the Campaign Legal Center and Protect Democracy indicates that vast swaths of the American electorate no longer are able to fulfill one of the most basic requirements of democratic citizenship: accepting election results.

Mounk writes:

Only one in three Americans who plan to vote for Trump said that if Joe Biden is declared the victor, that would be ‘because he receives more votes than Donald Trump.’ More than two in five said it would be ‘because voting systems are rigged and voter fraud is committed.’ Just one in five Biden supporters said that a win by Trump would be because he received more votes than Biden; nearly two in three said it would be due to ‘voter suppression and foreign interference’.

These are dreadful statistics. The noxious brew of politicians like the president sowing doubt regarding the election results, our polarized, contempt-ridden political climate, and our inability to confront a pandemic without resorting to culture war-style rhetorical slugfests have converged to render a critical mass of Americans unwilling to accept election results—one of the baseline requirements of participating in our centuries-long experiment in self-governance.

Why, one might ask, is accepting election results so fundamental to American democracy?

Because in America, elections are the prerequisites of politics, and politics is the only thing standing between our sustained, peaceful co-existence and a descent into internecine violence.

Citizens taking actionRead More

Politics is supposed to facilitate a shared answer to these trying questions. Politics is supposed to be a means by which we put forth competing viewpoints and visions, yes, but in doing so we also find the immense amount of common ground which we do indeed share and upon which we can build.

Having a legitimate election a number of rash, impassioned, self-interested beings to admit that they have lost something of great consequence. It requires that we submerge self-interest at the altar of the common good. It requires that we accept that there is such a thing as a common good in the United States of America in 2020 in the first place.

And if we Americans don’t have politics, if we don’t have good-faith, sustained political discourse, our all too apparent differences are sure to overwhelm us. In a multiracial democracy with a long and complicated history from which we are growing increasingly estranged, the absence of politics will entail violence. And we can’t have politics without legitimate elections.

But having a legitimate election requires self-control. It requires a number of rash, impassioned, self-interested beings—i.e., human beings—to admit that they have lost something of great consequence. It requires that we submerge self-interest at the altar of the common good. It requires that we accept that there is such a thing as a common good in the United States of America in 2020 in the first place.

The problem is that we don’t have very much of that sort of self-control sprinkled throughout our nation right now. Politics has been hijacked by a number of self-interested hacks, unschooled in our nation’s messy, complicated history (or political philosophy, for that matter), who are all the while aided and abetted by a citizenry either too caught up in their private affairs or too in love with frustratingly simplistic conceptions of politics, economics, and human nature in order to exert any semblance of a benign influence over our res publica.

Find common ground with your neighborsDO MORE

Adams was right to be scared. I’m scared of what this election will entail, of what will ensue between November and January. But I am also momentarily heartened by his imperfect interlocutor’s own political philosophy and unabashed faith in the reason of humankind.

In a letter to the Rev. Samuel Knox in 1810, Jefferson wrote: “truth & reason are eternal. they have prevailed. and they will eternally prevail[.]” Borne of common sense, Jefferson’s optimism was always tempered by reality, as he acknowledged that the victories of truth and reason were far from givens at any point in time: “however, in times & places, they may be overborne for a while by violence military, civil, or ecclesiastical.”

I look at the current state of American politics with terror, and I fear that that terror will only grow in the coming weeks, months, and years. But to those who are scared and fearful like myself: Do not drift into hysteria or a nihilistic shrugging of the shoulders. Rather, take faith in Jefferson’s wisdom, and your own responsibility, as a citizen, in helping bring it to fruition.

Thomas Koenig is a recent graduate of Princeton University from Oreland, PA. He will be attending Harvard Law School in the fall of 2021.

Header photo via Wikimedia