The debate over how to teach Black history in schools seems relatively modern. The problem behind it, however, is much older. And its solution is perhaps as ancient as a passage from the Bible’s Old Testament.

When historical figures die, the larger culture becomes responsible for telling their stories. In death, our leaders inexorably surrender their legacy to the living, and the living, typically the loudest voices in the room, ultimately determine what these figures are remembered for, what they symbolize, their lasting message. This is especially true when African American political agitators die, as their stories fall prey to institutionalized social and political distortion. Any historical fact that makes the dominant culture feel uncomfortable, that doesn’t suit the current narrative, goes by the wayside, and survivors who would have opposed this figure during their life are now able to sing their praises in death.

Distorting Black history

Consider Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. When King died, he was an outspoken critic of the Vietnam War. He spoke of American militarism, racism, and poverty as a three-fold axis of oppression. By April 4, 1968, he had become a Black radical, a pariah, unsupported by Black and White political leadership alike.

Today, however, Dr. King is remembered as a harmless historical figure invoked to justify the folly of color-blind political theory. The most hackneyed phrase of all of his speeches comes from his 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech: “content of their character, not the color of their skin.” American history has conveniently forgotten that by the time of his death, King had evolved his politics into a much different space — and that he’d become an American outcast. Instead, society, politics and the culture at large have reconstructed his legacy to portray him as someone he most certainly was not.

When African American political agitators die, their stories fall prey to institutionalized social and political distortion.

Something similar has happened to Muhammad Ali: despised draft dodger in life and hero in death. And it will one day happen to Colin Kaepernick, who is blackballed from the NFL now and a punching bag for those who hate protest. But we will likely praise Kaepernick when he is gone.

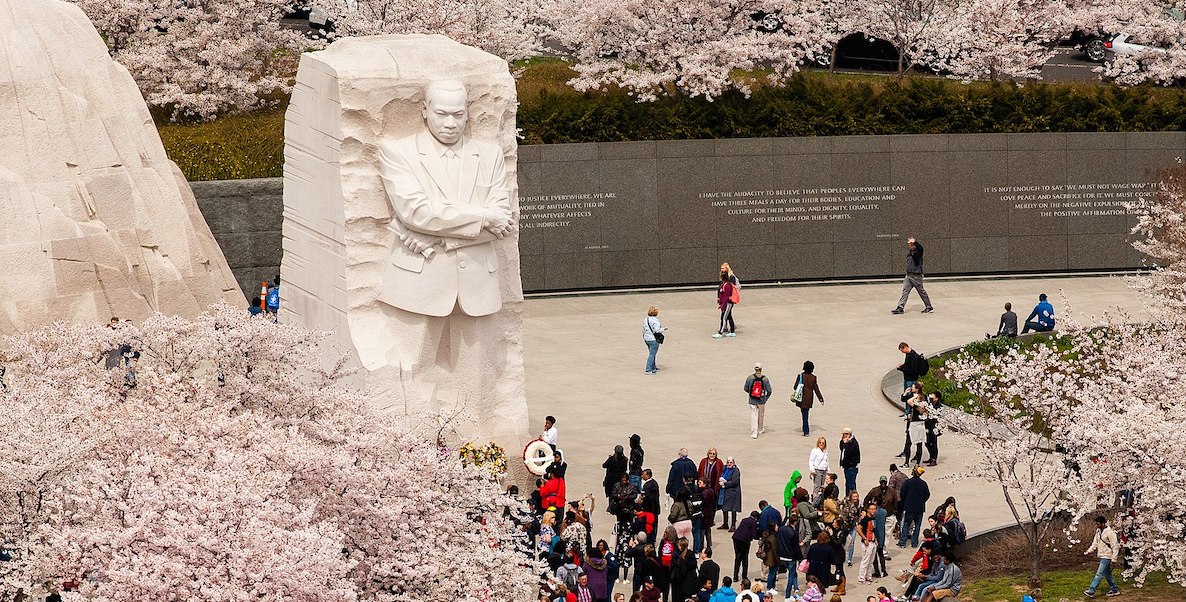

In other words, we celebrate people who can no longer agitate us. We adore monuments, but we despise movements. Why does that matter? Why is it so important to remember King, Ali, and Kaepernick for who they were, rather than who the culture has made them to be?

Remembering who they were

Because remembering them for who they actually were in life maintains their spirit of resistance to oppression in ways that inspire the current resistance movements. In King’s case, drawing from a distorted legacy of color-blindness does more to maintain the status quo than to fundamentally reform it. Understanding Dr. King as the courageous agitator he truly was is a far more effective and inspirational means to resist injustice in our contemporary world of police killings of unarmed Black citizens, voter suppression, and their connections to poverty — many of the same problems Dr. King faced more than half a century ago.

This is where a biblical tale from the Old Testament serves as a particularly vivid example of the importance of accurately remembering and retelling truth.

The book of II Kings 13:21 tells the story of a dead man tossed into the tomb of the prophet Elisha. Upon coming into contact with Elisha’s bones, the man instantly comes back to life. Interpret this tale literally, and it’s just another miraculous biblical resurrection. But consider the man as being psychically dead, as one who has forgotten himself, as one who, much like a person with retrograde amnesia, doesn’t know who he is, and we find a lesson that’s entirely relevant to this day and month.

We adore monuments, but we despise movements.

In the story, having forgotten his own identity, the Old Testament man finds lifesaving hope in reconnecting with his ancestral history, no matter how difficult or easy, ugly or beautiful. In order to come back to life, he must touch the bones of Elisha, a prophet, but also, a human skeleton. In encountering the reality of those bones, he can live again. This is the value of the truth. The truth will set you free — free to continue in the struggle for freedom.

Keeping Black legacies alive

What does this struggle look like today? What organizations are doing the work, staying close to the bones in order to carry the fight forward? Since there are so many ongoing civil rights movements (fair housing, voting rights, etc.) the answers to these questions are likely as varied as the struggle itself. That said, there are many well-established, reputable civil rights organizations that are worthwhile, such as the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, a group actively engaged in legal challenges to oppressive laws and governmental practices, a group that the “bones” of Dr. King — and not his distorted “color-blind” legacy — would support. Find an organization that you can support and get involved in a local chapter, in doing so, you pay tribute to Dr. King’s movement rather than paying homage to a false monument.

If Black history is American history, then to distort Black history is to distort American history, which, in turn, causes us us to distort — and eventually forget — who we are. Those who criticize the teaching of African Americans from 450 years ago to today would rather not go into the tomb and contact the bones; it smells too bad in there. Instead, they take the bones and turn them into something that we can stomach, something that tastes good in the mouth but that is bad for the rest of the body, when we ought to taste the hard truth of who King was in the mouth, so that we can be better off on the inside — deeper thinking and more committed people with an intolerance for injustice so high, that, like, King, we can resist injustice at every turn.

We must never forget to touch the “bones.” We must maintain contact with the true legacy of Black political agitators, for when we do, our monuments become tombs into which we can come into contact with the “bones” of Black heroes and heroines, and, like the man in the biblical story, we can be inspired, “resurrected,” at the monuments. Otherwise, our most cherished monuments that celebrate Black leadership become mere tombs where movements go to die.

Timothy J. Golden, J.D., Ph.D. is Visiting Professor of Philosophy at Whitman College. He was a criminal defense lawyer in Philadelphia for nearly 20 years.

The Citizen welcomes guest commentary from community members who represent that it is their own work and their own opinion based on true facts that they know firsthand.

![]()

MORE ON BLACK HISTORY, THE RIGHT WAY

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.