In the recent national academies report titled, “Securing the Vote: Protecting American Democracy,” the committee was clear in their recommendation that “Elections should be conducted with human-readable paper ballots. These may be marked by hand or by machine, such as a ballot marking device (BMD).”

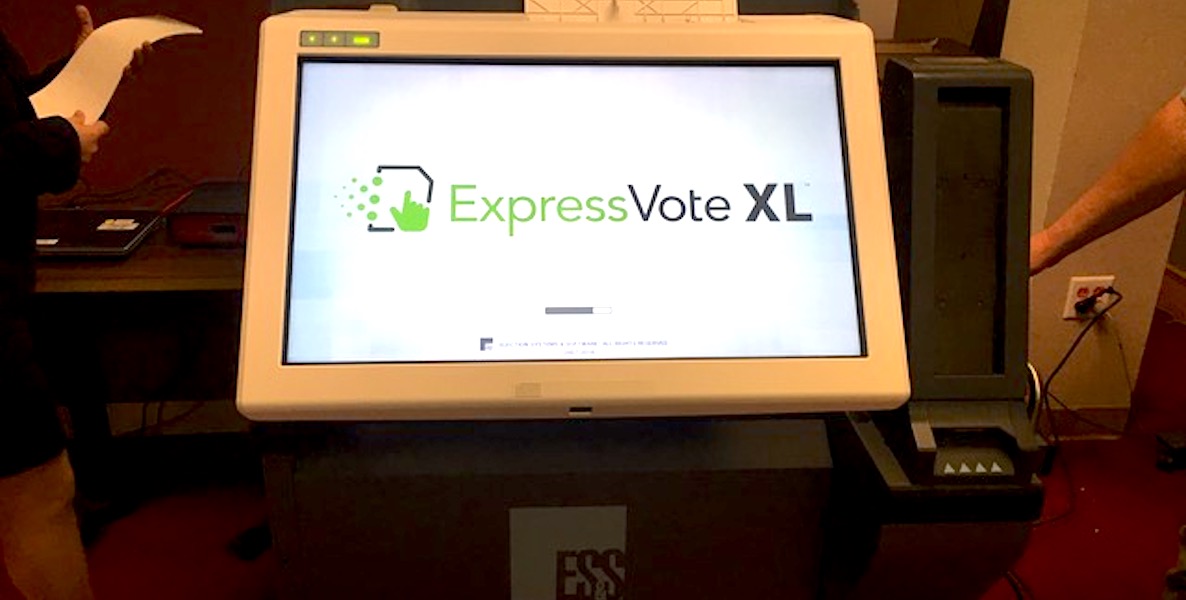

Following the release of the report, many states are moving away from paperless voting machines to hand-marked paper ballots or BMD. At the onset, it is important for voters to understand the difference in voting processes and how their votes are cast and counted.

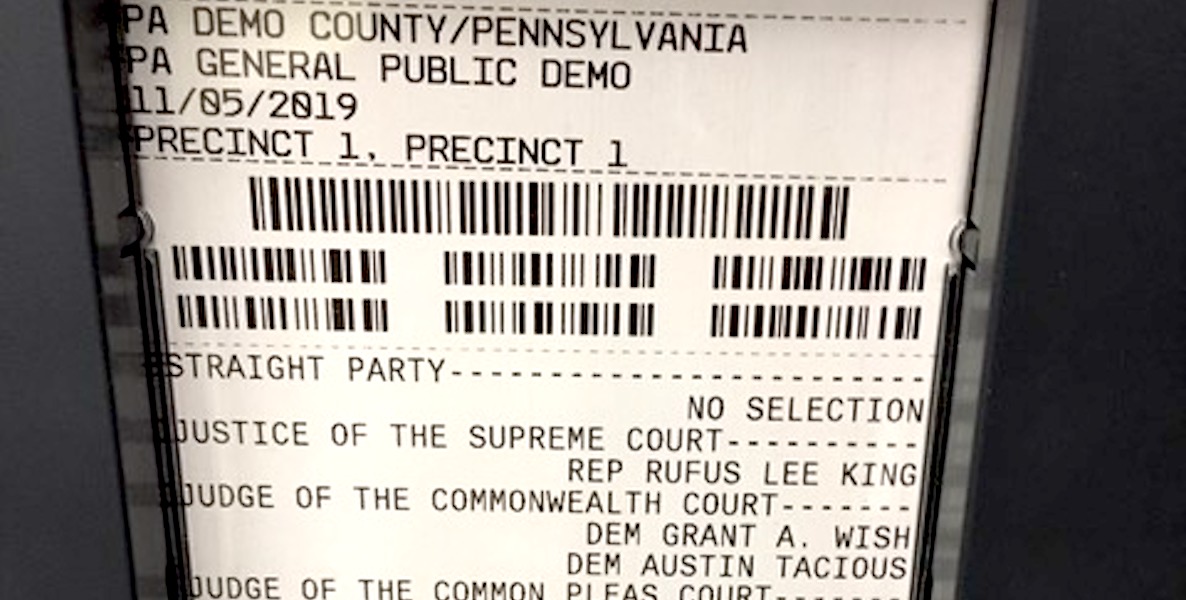

Voters in Philadelphia will be using their new voting system in November—a BMD. It is similar to the city’s current system but voters’ selections will be printed on a paper ballot that shows the contest and the voters’ selections with a bar code above the text. The bar codes are read by scanners once the ballot is cast.

In this case, some are concerned that the barcode may not match the human-readable portion of the ballot. To ensure a match, the national academies report recommends that all elections should undergo an audit, for example a risk-limiting audit (RLA). This recommendation also applies to hand-marked paper ballots as well because they are fed through a scanner for tallying. The audit would ensure that the election results are accurate and would neutralize any barcode mismatches.

Hand-marked paper ballots, unlike BMD voting, are susceptible to overvoting and undervoting hacks. The undervote occurs when a voter decides not to make a selection in a contest, in other words, they leave the contest blank. An insider could then make a selection on that ballot. This will take two-to-five seconds and it’s impossible to detect if the insider is not caught in the act. The overvote hack occurs when the voter makes a selection, but the insider makes an additional selection causing an overvote, which would lead to a nullified ballot. Like the undervote hack, this is undetectable unless the insider is caught in the act.

![]()

The gold standard for securing elections should be the audit. If necessary, a full manual recount should be possible. With this in mind, the BMD has an advantage over hand-marked paper ballots. Hand-marked paper ballots will suffer from ambiguous marks that are left to the auditors to interpret. This doesn’t happen with the BMD. Some may say that the number of ballots that have this issue are small, but we have seen margins of victory very small, even down to one vote.

Most importantly, every vote should count and every ballot should be auditable. Voters need to understand how their devices and systems will be casting their votes, and they should be assured that the process will be secure and accountable.

Juan E. Gilbert is the Andrew Banks Family Preeminence Endowed Professor and Chair, Computer/Information Science/Engineering Department at University of Florida.

Photo via Kelley Minars Flickr