Like many other high-profile urban downtowns across the U.S., Philadelphia’s Center City has lost its share of large-format retailers in recent years, including Zara, Forever 21 (since relocated within Center City), Modell’s, Gap, Century 21, H&M (one of two), Barnes & Noble (since relocated within Center City), Marshalls, Target (one of two) and West Elm, along with a number of other well-known names like Ann Taylor, Talbots and ALDO.

In Philadelphia, these closures have commingled in the public imagination with the widely-publicized contraction of two Pennsylvania-based brands in Center City — Wawa, the convenience store giant which has shuttered five locations there since 2020, and Rite Aid, which has closed three and entered bankruptcy.

Meanwhile, 2023 Brookings Metro research indicated that, again, like many downtowns across the country, Center City has been suffering from perceptions of rising crime and disorder on its sidewalks and in its subways. Even though it is statistically safer today than in 2019, there could be little doubt that such anxieties have deterred foot traffic.

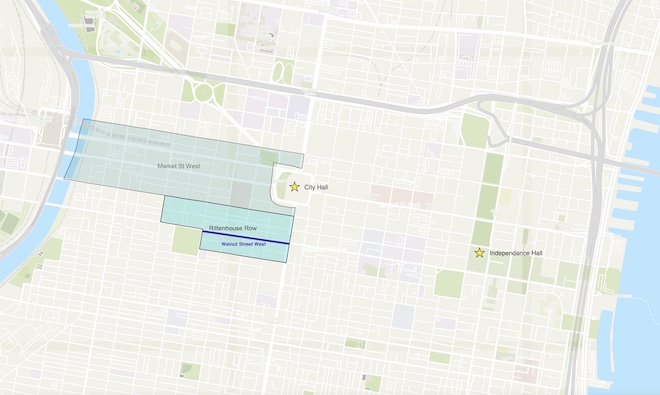

Finally, Rittenhouse Row sits just a block away from Center City’s canyons of Class A office towers in the “Market Street West” district (see map below). Home to roughly 38,000 non-resident workers in February 2019, it was still only drawing 60 percent of them — about 23,000 — as of February 2024, a considerably slower recovery than the 72 percent for Center City as a whole.

For all these reasons, one would expect to find retail conditions at crisis levels. Indeed, many Philadelphians perceive Center City in such terms. And in the early years of the pandemic, they were right. The availability rate along the West Walnut stretch reached as high as 25 percent in 2020, with roughly half of the storefronts shuttered in the 1700 block, the most highly coveted of the four.

However, an evolution of Rittenhouse Row that began almost undetected, amidst the so-called “retail apocalypse” in the second half of the last decade, has not only resumed since those dark days of 2020 but accelerated still further, with Walnut Street enjoying its greatest surge in new leasing activity since the late 1980s and with the vacancy rate having dropped to 11.5 percent as of May, 2024 (versus 16.4 percent for Center City as a whole).

This ascension, though, is not just about numbers, but also, the kinds of tenants that are taking interest and opening stores there. Indeed, the last several years have witnessed Rittenhouse Row’s arrival into the highest echelons of urban shopping precincts nationwide, worthy of mention in the same conversation as Boston’s Seaport District, Washington, D.C.’s Georgetown and Venice Beach’s Abbot Kinney.

It is increasingly a must-have location for the digitally native and other expansion minded fashion retailers that comprise a contemporary “Class A” tenant mix, boasting the likes of Warby Parker, Glossier, Third Love, Faherty, Marine Layer, Apple, Lululemon, Alo Yoga, Athleta, Vuori, Reformation, Aritzia, Madewell, Free People, Gorjana, Aesop and Bluemercury, as well as NIKE’s first Michael Jordan-branded “World of Flight” store in the U.S.

In making this climb, Rittenhouse Row has become the counter-narrative hiding in plain sight, offering proof that having the right sorts of retail spaces on the right kind of shopping street, amidst an absence of viable alternatives, can more than overcome the reduction in daytime employment as well as concerns about public safety in a downtown setting.

It’s not about the cubicles…

Rittenhouse Row’s appeal to retailers does not rest on daytime office workers but rather, full-time residents. Roughly 78,000 people live in “core” Center City today, for a density of 27,500 people per square mile, and another 135,000 in “extended” Center City, for 23,000 — in both cases, ranking fourth among large U.S. downtowns. Approximately 153,000 reside within a 30-minute walk (versus just 5,400 for King of Prussia Mall).

Such enviable densities are partly the result of Philadelphia’s foresight in offering a 10-year tax abatement for residential conversions of vacant office buildings in 1997, which has since been used for 40 structures totaling 8.8 million square feet. The 78,000 people in the core today represents nearly a doubling of the roughly 40,000 that lived there in 1990, and the 135,000 in extended, an increase of 26 percent from the 107,000 in 1990.

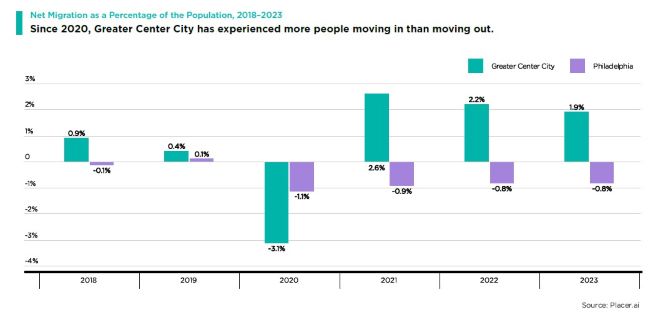

Like most large downtowns, Center City experienced urban flight in 2020 but resumed its growth trajectory in 2021. According to Placer.ai data, there was a net in-migration of 12,100 people to “Greater” Center City (core + extended) from 2021 to 2023 (see graph below), and by November of 2023, residential foot traffic was 34 percent higher than four years earlier.

Moreover, the residential contingent in and around Center City is by far the most demographically desirable in all of Philadelphia. Over 80 percent in the core boast bachelor’s degrees or higher (as opposed to 34 percent citywide), with a median household income of $95,000 (versus $58,000), while the numbers are 68 percent and $98,000 in the extended.

In fact, the region’s four wealthiest zip codes based on density of affluence — Rittenhouse / Logan Square, Queen Village / Bella Vista, Society Hill / Old City and Fairmount — are all in Greater Center City. On the national level, these four rank #24, #43, #50 and #102, respectively, while the first suburban one — Wynnewood, on the Main Line — does not appear until #295, with other well-known affluent enclaves not even in the top 500.

In addition, just 5 percent (core) and 17 percent (extended) of the households have children, translating to even greater discretionary spending (versus 27 percent for Philadelphia as a whole). Indeed, Center City’s population contains an especially large percentage of the young professionals who have been fueling the popularity of so many of today’s A-list brands. Twenty- to 34-year-olds comprise 53 percent and 49 percent (versus 26 percent citywide and 21 percent metro-wide).

With Independence National Historical Park as well as various other attractions, the district also benefits from a sizable number of impulse-spending leisure travelers. The visitor segment that has fueled the industry rebound nationwide and the only one in Center City that has fully recovered to pre-pandemic levels, it accounted for 1.1 million room nights there in 2023, or 34 percent of the 3.2 million total, according to Tourism Economics data provided by the Center City District.

Indeed, in Center City District’s analysis of the foot traffic in the nation’s 26 largest downtowns as of Q2 2023, Philadelphia ranked sixth-highest in the post-pandemic recovery of visitors from beyond Greater Philadelphia (84 percent), and first among Northeastern/Midwestern cities — which is not entirely surprising, given the heavily domestic skew of its historic draws.

Furthermore, while major tourism drivers like Independence National Historical Park and Old City are located well east of Rittenhouse Row, the overwhelming majority of Center City’s 58 hotels and roughly 13,100 rooms sit within walking distance of the shopping destination.

Given the metro’s immense footprint and population, Center City is also able to count a large number of “day-trippers” from other neighborhoods and suburbs, which has no doubt helped to soften the blow from the pandemic-era contraction in out-of-town tourism. Of the 26 largest downtowns, it enjoyed the fifth-strongest recovery in visitors from within their respective regions (85 percent), and first among Northeastern and Midwestern cities.

These visitor segments combined for 56 percent of Center City’s foot traffic as of late November 2023. Along with the 18 percent from residents, the two submarkets today represent nearly three-quarters of the pedestrians walking the sidewalks of Philadelphia’s downtown core (versus just a quarter for daytime workers).

It’s not just about consumer demand

Consumer demand, however, is only part of the explanation. Rittenhouse Row also offers both the scale and character as well as the ground-floor spaces — with mostly 1,000 to 3,000 square foot storefronts along a well-proportioned, tree-lined thoroughfare — that today’s A-list brands have been seeking.

This is a function of its history, as a fashionable 19th-century residential neighborhood (or “horse-car suburb”) separate and distinct from the city’s central business district to the east of City Hall and Broad Street. Indeed, Rittenhouse Row was lined with stately townhomes until the 1910s and early 1920s, occupied by the aristocratic families that constituted the city’s elite.

It was in those decades, when they started to decamp via commuter railroad or private automobile to the Main Line suburbs, that the central business district’s westward spread crossed Broad Street and the reincarnation of Rittenhouse Row as a swanky shopping street began to take shape. By the mid-1940s, West Walnut Street had become so established in this regard that the City saw fit to propose an underground parking garage below Rittenhouse Square.

And yet, the four blocks of Rittenhouse Row never lost their neighborhood scale or fine grain. Indeed, Rittenhouse Square as a whole has largely been spared the disruption of urban renewal and redevelopment, while (mostly) managing to avoid any major fires. Protected as well by the vigilance of active community organizations, its built form remains remarkably intact even today.

Moreover, while the kinds of stores has evolved over the decades — from West Walnut Street’s period as Philadelphia’s “Fifth Avenue” in the 1990s to the predominance of more accessible priced “neo-hipster” brands now, from its peppering of independently owned boutiques until the mid-2010s to its largely chain filled mix today — the critical mass of smaller shops selling fashion has been a constant.

Clearly, the realities of what is happening on the ground are a lot more complex and nuanced than the noisy narratives would suggest.

Indeed, such established co-tenancy helps to explain its gravitational pull. Comparison goods retailers generally seek districts and centers where large numbers of other such stores already exist, to leverage the cross-traffic thus generated. In their minds, “Rittenhouse Row has always been thus, so thus it always will be.”

In this sense, Rittenhouse Row towers above the city’s other alternatives. While several other Philadelphia neighborhoods have gentrified along with Center City in recent decades, their commercial corridors do not even approach the same level of co-tenancy or daytime footfall. Resurgent ones like Fishtown’s Frankford Avenue and South Philadelphia’s East Passyunk Avenue still draw largely on the basis of buzzworthy food and beverage, not shopping.

The choice, then, becomes rather straightforward. Even with rents that can be more than three times higher, West Walnut Street is still, for many brands, their one and only location within city limits, if not the region as a whole. Indeed, Rittenhouse Row’s competitive advantage in the urban core effectively leaves a large number of Philadelphia’s 1.6 million people (and 195,000 households earning $100,000+) squarely within its trade area.

In fact, retailers either unable to find a landing spot on Walnut Street or unwilling to pay top-dollar for one are more likely to cast their gaze towards Chestnut Street, running parallel just a block to the north, than play the role of pioneer or opt for still cheaper space in one of the neighborhoods. With rents on Chestnut that can be roughly one-third lower than Walnut’s, the former has clearly emerged as an alternative to the latter in the last decade or so, for independently owned boutiques, value oriented concepts as well as Class A cosmetics brands.

Of course, the presence of a shopping street like West Walnut — with its smaller floorplates and more intimate scale — is not unique to Center City. Chicago’s Magnificent Mile can point to Oak Street, and San Francisco’s Union Square, to Maiden Lane. The difference is that luxury fashion houses — the “A+” brands — have historically predominated in those corridors and could outcompete “neo-hipster” brands for space there. With rents averaging $432 per square foot in 2023, Oak Street was the eighth-most expensive retail destination in the Americas, according to Cushman & Wakefield.

Center City, on the other hand, has never quite reached the first tier of luxury shopping destinations. Rittenhouse Row did once have a more ritzy component — particularly in the late 1980s when several such brands materialized in the lobby of the redeveloped Bellevue-Stratford Hotel, at Walnut and Broad Street — but ultimately, according to Larry Steinberg, senior managing director at Colliers, “high-end retail didn’t prove to be a very successful model for the street.”

One could plausibly argue, then, that the absence of such A+ luxury brands and operators in Walnut Street’s case — with a few exceptions like Tiffany & Co. and the 1916 Company’s Govberg Jewelers — opened the proverbial door for its current collection of Class A neo-hipster concepts that in other cities have been compelled to locate along similarly-scaled corridors in the near neighborhoods, like W. Randolph Street in Chicago’s West Loop and Hayes Street in San Francisco’s Hayes Valley.

Clearly, the realities of what is happening on the ground are a lot more complex and nuanced than the noisy narratives would suggest.

(I want to offer a special thanks to the people at the Center City District — Paul Levy, Prema Katari Gupta, Clint Randall and Jimmy Salfiti — for all of the data, visuals and support that they provided, as well as Paige Jaffe of Square Retail Consultants, who made the time to talk with me about retail leasing dynamics in Center City and across Philadelphia).

Michael Berne is president of MJB Consulting, a retail planning and real estate consultancy based in New York City and the San Francisco Bay Area. This is part 2 of his 5-part series looking at American downtowns. You can reach him at mikeberne@consultmjb.com.

The Citizen welcomes guest commentary from community members who represent that it is their own work and their own opinion based on true facts that they know firsthand.

![]() MORE DOWNTOWN DEVELOPMENT SOLUTIONS

MORE DOWNTOWN DEVELOPMENT SOLUTIONS