There has been a lot of handwringing over the phenomenon of fake news of late. It started with those made up Facebook stories during the election, many of which went viral—that the Pope had endorsed Donald Trump, for example, or the one headlined, from the phony Denver Guardian, “FBI Agent Suspected in Hillary Email Leaks Found Dead in Apparent Murder-Suicide”—and it has led to some interesting and necessary reforms. After initially dismissing the controversy, Mark Zuckerberg announced that Facebook would work with fact-checking organizations to review stories that users flag as potentially fake. And, in a 36-hour hackathon, college students came up with an open-sourced algorithm designed to authenticate what is real and what is made up on the platform.

These are good developments, but I wonder if the scourge of fake news isn’t better taken on first with a more introspective approach, one that asks a more fundamental question: Just what is our responsibility—yours and mine—as citizens and as news consumers? Are we to be passive recipients of information, waiting for technological protection from lies and half-truths, or ought we to be active participants in the public conversation?

Citizenship is not a spectator sport. That means it’s up to us to do the hard work of determining what is true and what is false in the public sphere. Remember the movie All The President’s Men, when Woodward and Bernstein—played by Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman—were under strict orders not to publish even on-the-record facts without a corroborating second source? Well, technology has rendered each of us, in effect, our own editor-in-chief. We gatekeep our own news now. So maybe it’s time for us as citizens to adopt the Woodward and Bernstein standard for ourselves and not believe anything if we haven’t corroborated it by actively seeking out reports from other outlets.

The onus, in other words, as the ultimate arbiter of competing sets of facts in the marketplace of ideas, should be on us—and not on magic-bullet algorithms. Where it gets tricky, however, is when we move beyond issues of verifiable fact and into the realm of context and interpretation. That’s where a more insidious threat lies—both to the integrity of public debate and to the future of democracy.

The notion of objectivity (as opposed to fairness) is precisely part of the problem. “The principle of objectivity [has made us] passive recipients of news, rather than aggressive analyzers and explainers of it,” wrote Brent Cunningham in The Columbia Journalism Review during the Iraq War.

Beginning on Christmas Day, we were treated to a local example of just how nuanced real fake news can get. As has since become quite well known, George Ciccariello-Maher, an associate professor in Drexel University’s politics department, tweeted “All I want for Christmas is White Genocide” on Christmas Eve. In reaction to the resulting cyberspace outrage, he followed that up with: “To clarify: when the whites were massacred during the Haitian revolution, that was a good thing indeed.”

Most news stories accurately reported his tweets, as I’ve just done. But is that journalism, or stenography? Yes, the professor’s tweets were dutifully reported, as was the uproar in response to them, as well as Drexel’s statement, calling its employee’s comments “utterly reprehensible” while reasserting its commitment to free speech. But all that reporting ultimately shed far more heat than light. With a few exceptions, the media coverage of l’affaire White Genocide amounted to a much more insidious form of fake news than we’re accustomed to, because it promulgated a false narrative: That a leftist professor wanted to kill white people. And the dissemination of that narrative played into the hands of those who had orchestrated it. In this, the mainstream media was duped, an unwitting accomplice in the spreading of a false story.

The most salient fact ignored by much of the coverage was that Ciccariello-Maher was referencing—and not inventing—a real phenomenon, the rise of a “White Genocide” meme in the alt-right universe that holds that everything from intermarriage to diversity is a conspiracy to obliterate the white race. It doesn’t take much in the way of research to conclude that Ciccariello-Maher was mocking those extremists who perpetuate this view; hell, a simple Google search takes you to the mind-numbing whitegenocideproject.com and to example after example of stories on sites like Breitbart and The Daily Caller designed to advance the notion that to be white is to be under existential threat in America. So it’s no surprise that The Daily Caller lead about Ciccarello-Maher alleged that the professor “had a long history of espousing racist views towards white people on Twitter and has at times supported genocide.”

What was surprising, however, was the relative absence of this context in the mainstream reporting about the controversy. In The Inquirer, for example, a story by Jonathan Tannenwald and Inga Saffron quoted the professor in his own defense, but otherwise—in keeping with the tradition of objective, or what they consider “neutral”, reporting—played the question of whether the professor really wanted to kill white people pretty much down the middle.

They quoted the professor from an email he’d sent: “On Christmas Eve, I sent a satirical tweet about an imaginary concept, ‘white genocide.’ For those who haven’t bothered to do their research, ‘white genocide’ is an idea invented by white supremacists and used to denounce everything from interracial relationships to multicultural policies…It is a figment of the racist imagination, it should be mocked, and I’m glad to have mocked it.”

The next day, Saffron made another nod at getting at the full context: “But to Ciccariello-Maher, who is white—and who has written extensively on racism, policing, social inequality, and colonialism—the phrase white genocide is shorthand for those who support policies that can harm and oppress minority groups, like blacks and immigrants.”

Over at Billy Penn, another brief jab at context was made: “…[Ciccariello-Maher] considers the concept of ‘white genocide’ to have been invented by white supremacists. And white supremacist groups are the groups that have commonly used the phrase. The White Genocide Project, for instance, claims mass immigration and assimilation could count as genocide.”

Get More From Every Story

We include boxes in nearly every story to help you take action. Click the boxes below to see how you can make Philly better.

But does this reporting go far enough? Is it enough to make a nod, in a few sentences, or within a quote from Ciccariello-Maher himself, that there exists within the white supremacist subculture a white genocide theme…and it was that that the professor was taking on? Mentioning it in passing, or by including a mention of this context in a quote from Ciccariello-Maher, essentially doubles down on the timeworn tenets of “he-said/she-said” reporting. It makes it an arguable proposition as to whether or not the idea of “white genocide” is a deliberate meme advanced by racists…when a cursory Google search proves that it is not. It is, in other words, verifiable fact that the alt-right has been trucking in this white genocide narrative, and that Ciccariello-Maher’s tweets, though easily misinterpreted, were responding to that false narrative. Such reporting, though appearing to be evenhanded, actually plays into the alt-right’s ideological hands by holding open the possibility that this wild leftist professor would like to see white people murdered.

When I caught up with Ciccariello-Maher last week, he wasn’t cowed, and he walked me through the nature of the orchestrated campaign against him. “Yes, tweets are open to misinterpretation,” he concedes. “But there are mechanics behind that misinterpretation. The smooth machinery of the alt-right on Twitter and Breitbart saw this as a trial run on the cusp of the Trump moment to see how far they could get with something like this. When the mainstream media and Drexel weren’t savvy enough to see this for what it was, it was seen as a triumph.”

The morning after Ciccariello-Maher’s first tweet, he says, he woke up to hundreds of emails containing death threats—all cleverly containing subject lines like “Fall Syllabus” designed to guarantee they’d be opened. Given that media bias runs much more toward simplicity than ideology, it ought not to be too surprising that, when the coverage took off, the narrative predictably fell into line: A lefty prof was calling for the killing of white people. Left unsaid: Just how out of touch with mainstream values and common decency are our institutions of higher learning?

But some outlets got it right. Over at teenvogue.com, of all places, De Elizabeth walks us through the controversy in a way that goes deeper than daily stenography. “It’s cause for concern when Teen Vogue gets it better than a university or much of the mainstream media,” says Ciccariello-Maher.

And at slate.com, in a piece headlined “Drexel University, Apparently Unfamiliar With White Supremacist Lingo, Censures Prof For ‘White Genocide’ Tweet,” Matthew Dessem brilliantly takes us on a tour through the hate-filled history of the meme, introducing us to the late David Lane, a terrorist, white supremacist and the murderer of talk show host Alan Berg in 1984, who authored the “White Genocide Manifesto”: “Let it be understood that the term ‘racial integration’ is a euphemism for genocide. The inevitable result of racial integration is a percentage of interracial matings each year, leading to extinction, as has happened to the White race in numerous areas in the past. As the White remnant is submerged in a tidal wave of five billion coloreds, they will become an extinct species in a relatively short time. This genocide is being accomplished by deliberate design.”

Citizenship is not a spectator sport. That means it’s up to us to do the hard work of determining what is true and what is false in the public sphere.

Dessem concludes: “As soon as it became advantageous to pretend Ciccariello-Maher was referring to literal trains and camps instead of mocking the histrionic code words of a pack of racists, Breitbart was there, ready to lead its moronic light brigade into battle.”

Now, some might say that Dessem’s conclusion isn’t objective. Indeed, I could do without the name-calling; I prefer to let the reader, moved by fact-based argument, do his or her own name-calling. But the notion of objectivity (as opposed to fairness) is precisely part of the problem. The tenet of objectivity, it bears keeping in mind, only became a journalistic standard in the 1800s, mostly out of fealty to advertisers who objected to partisan points of view in the news. Fast forward a couple of hundred years and the limits of what has become the newsroom ideology of objectivity is clear. “The principle of objectivity [has made us] passive recipients of news, rather than aggressive analyzers and explainers of it,” wrote Brent Cunningham in The Columbia Journalism Review during the Iraq War.

Cunningham points to Just the Facts: How “Objectivity” Came To Define American Journalism, a 1998 history of the origins of objectivity in U.S. journalism, to prove that, even as early as the turn of the 20th Century, the flaws of so-called objective reporting were evident. “[Author David] Mindich shows how ‘objective’ coverage of lynching in the 1890s by The New York Times and other papers created a false balance on the issue and failed ‘to recognize a truth, that African-Americans were being terrorized across the nation.’”

The coverage of George Ciccariello-Maher’s Christmas Eve tweet is further proof that we are still awash in false balances and false equivalencies. But, when you combine that with the speed with which media travels today, with an electorate easily distracted by shiny objects, and with a power elite well schooled in how to divert our attention, well, that’s a recipe for the crumbling of democracy. If you picked up a newspaper on December 26 and read about this Drexel professor who tweeted about wanting “white genocide” your reaction was likely just like mine: “Wait a minute? What? What does that mean? Does this guy want to kill white people?”

This is where we come back to the responsibilities of citizenship. The more I searched for real answers, the more I learned about the alt-right and its campaign to make “white genocide” something real and part of the zeitgeist. In messy times, being a news consumer is going to be harder and more complicated. It just may be that our foremost common cause—journalist and citizen alike—is to resist the urge to default to simple storylines.

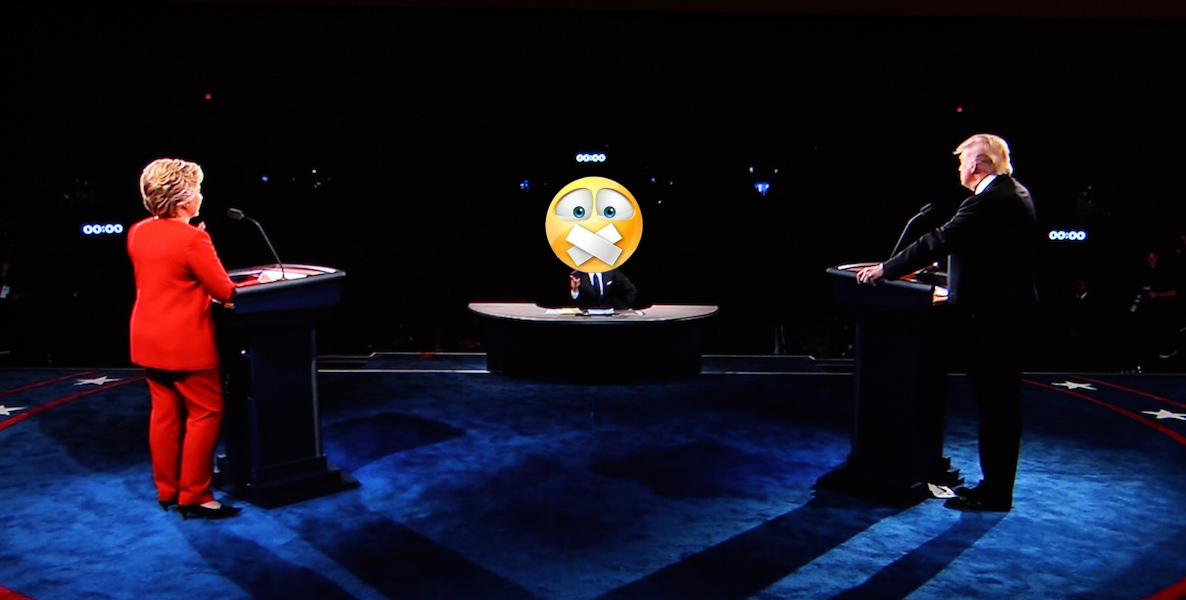

Header photo by Daniel R Blume via Flickr.