Remember when we visited other people’s homes? That was a nice thing. Sometimes new acquaintances would ask: “What do you do?”

That would inevitably lead to more questions about the phrase “Future of Work.” While it has been around for years, it turns out most people don’t know exactly what it means—for them, their future and the future of their city.

Nor do they understand that, like other major disruptions such as pandemics and climate change, Future of Work shifts are likely to harm Black workers and communities worse than other groups.

And so, it would begin, a more intense conversation than expected. Below you’ll find five FAQs dating back to the era of indoor socializing—but more relevant now than ever.

5 FAQs about the Future of Work

1. What is ‘future of work’?

Future of Work refers to the ways new technology affects how we access and do work as evident in three trends:

- Erosion of whole industries as consumers let go of the tactile and embrace digital. Remember Blockbuster? Tower Records? Disruptive companies like Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix and Google deployed tech and flipped the tables on how we create and consume news, music, photos, films and more. These companies are now powerful anchors in the hygienic, user-friendly, virtual world.

- Automation of work tasks. Retail cashiers first saw bar codes, then self-checkout and of course, online shopping. Each new thing reduced work for cashiers. In the Philadelphia area there are over 69,000 cashiers. The Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia estimates a 97 percent probability of automation for cashiers over the next 10 years.

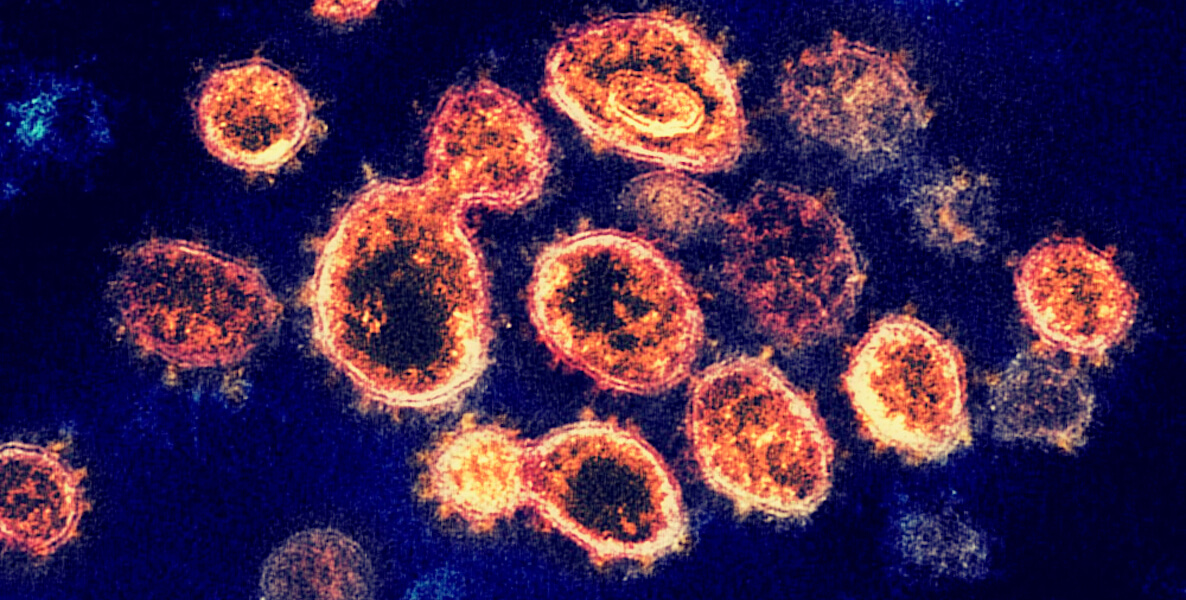

I had hoped small businesses would be a safe haven for cashiers because they adopt technology more slowly. However, the pandemic threatens their very existence. Across the economy, all dirty, dull or dangerous jobs are prime candidates for automation. In sum, about 320,000 jobs in this region are highly likely to be automated by 2030. Overall, 18.2% of jobs held by Black workers are at high risk of automation in our region.

Additionally, artificial intelligence is a threat to many office jobs. College graduates are not necessarily safe because A.I. can automate operational processes such as filing insurance claims and securing loans.

- The changing relationship between workers and employers. Increasingly, more people are independent contractors or gig workers. In Philadelphia, since Uber exploded in 2014, there has been a 16x increase in the number of 1099 self-employed tax filers. Uber does not currently recognize any drivers as employees. This allows them to avoid contributions to safety net programs like unemployment insurance and sick leave. Platform companies and regulators are battling it out over employee misclassification in California. The pandemic adds a new twist in the trends: Will work-from-home further loosen formal ties between employer and employees and expedite the growth of the gig economy?

2. Hasn’t technology always changed jobs? Why so much hype?

Projections about jobs being augmented or eliminated are wide-ranging. Yes, the economy has shifted jobs from humans to machines before. However, unlike past industrial shifts, today’s advances are much faster, with less time for humans and our stodgy institutions to adapt. Technology is fueled by Moore’s Law of exponentially growing computer power. News of innovations are shared overnight, globally.

Moreover, past shifts meant painful reductions in wages, and this is happening today too. Labor supply exceeds labor demand for many people’s skill levels. When people are not employed, it has corrosive effects on society and more die from diseases of despair.

Sure, new jobs will be created. For example, the City of Philadelphia had no dedicated digital media pros just a few years ago. Now, there is an entire unit dedicated to social media management. New jobs will definitely be created for some. But it will be very rocky for people who lack marketable talent and/or skills if safety net policies and ladders to opportunity do not get stronger.

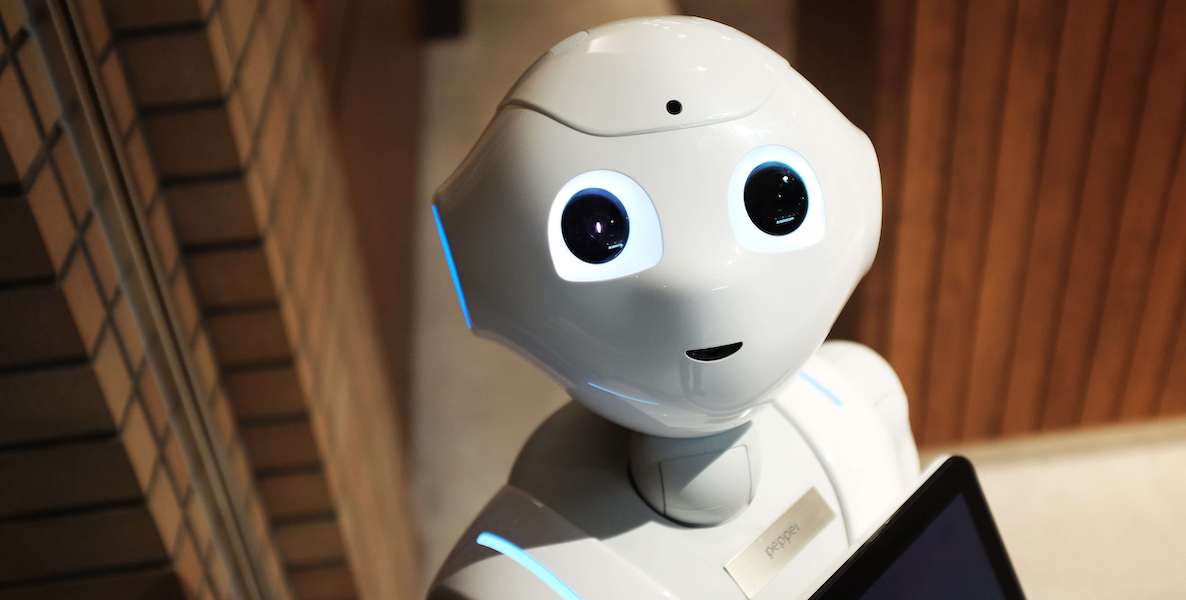

3. Will robots take my job?

![]() The better questions are: Will my skills match the jobs of the future? Will the future job pay enough to live a decent life? The U.S. has not effectively created adequate support for opportunity and economic mobility. Racism inhibits the creation of strong safety net policy. Hopefully, our national reckoning with racism will help address our shoddy safety net.

The better questions are: Will my skills match the jobs of the future? Will the future job pay enough to live a decent life? The U.S. has not effectively created adequate support for opportunity and economic mobility. Racism inhibits the creation of strong safety net policy. Hopefully, our national reckoning with racism will help address our shoddy safety net.

Regardless, individuals will need to constantly upgrade skills either on their own or with the help of forward-thinking employers. The skills most in demand in the future will be a )distinctly human skills such as creativity and empathy; b)technology skills. Only Humans Need Apply: Winners and Losers in the Age of Smart Machines by Tom Davenport and Julie Kirby is a good guide.

If you still really want to know if a robot will take your job, you can get the odds here.

4. When is the Future of Work?

![]() The future of work is now. It has been underway but not enough leaders have been paying attention. Many institutions are averse to change, even though they may talk a good game. Companies do not want to offer advance notice on plans to eliminate jobs. Political leaders have few incentives to deal with complex problems beyond the scope of their term in office.

The future of work is now. It has been underway but not enough leaders have been paying attention. Many institutions are averse to change, even though they may talk a good game. Companies do not want to offer advance notice on plans to eliminate jobs. Political leaders have few incentives to deal with complex problems beyond the scope of their term in office.

Now what? The solutions exist, given the will. But, solutions require creativity and crowdsourced leadership from many sectors, many diverse minds. More on this in future posts.

The pandemic, plus an economic coma, followed by civil unrest and a long overdue racial reckoning have now all combined to call the question: What can we build better? How can we ensure real opportunity for all? There are viable solutions.

5. But the most important FAQ: Will we do it?

We’ll all have to stay tuned for the answer to that one …

Anne Gemmell is former Director of Special Initiatives in the City of Philadelphia Office of Workforce Development, where she was responsible for creating strategic plans related to the Future of Work, focusing on emerging technologies, their effects on talent pipelines and actions for “future-proofing” our local economy. A longtime policy strategist, she also worked with the Kenney administration on the equitable design, advocacy and successful funding of the PHL PreK program.