At one point during Free Meek, Amazon’s gripping five-part docuseries that chronicles the North Philly rapper’s Kafkaesque itinerary through the criminal justice system, the 32-year-old corrects the impression that his 12 years in the mess that is our parole and probation maze was somehow aberrant. “I never looked at it is a nightmare, I looked at it as real life for a black kid in America,” Mill says. “This is real life.”

Mill’s very real experience included 23 hours a day in a cage, for the sin of non-criminal “technical” violations of probation such as popping a wheelie on a city street, and it featured a weird fixation on him by a judge seemingly more concerned (as even her own defense lawyer, in a stunning scene, concedes) with her own issues of control—rather than dispassionately meting out justice. That experience ended last week when, the case finally having been removed from Common Pleas Court Judge Genece Brinkley, a deal was struck and Mill pled guilty to a 12-year-old gun charge (which he’d never denied), leading Common Pleas Court Judge Leon Tucker to say: “I know it’s been a long road for you, and hopefully this is the end of it.”

With that, for the first time in over a decade, Meek Mill was free.

Mill may finally be in the clear, but the documentary stands as an indictment of a broken system. It raises serious concerns about just how much justice there is in our criminal justice system, particularly for the powerless—which Mill was when he was first arrested, and badly beaten, over a decade ago on what the film suggests were corrupt charges. And it raises questions about Meek himself; in the past, I’ve written that, while Mill’s case sheds light on inequities, we ought not to deify him: Meek Mill is no Nelson Mandela. Yet the Amazon doc—granted, it was produced by Mill loyalists—can only lead to a reconsideration of Mill, both as an evolving artist and as a newly-awakened social activist.

First, the systemic implications. When Judge Brinkley sentenced the rapper to two to four years in prison in 2017 for violating his probation, the prosecution wasn’t even seeking jail time. That wasn’t the only head-scratcher. In fact, Brinkley had been downright weird about the case for years. She showed up at Broad Street Ministries, where Mill was supposed to be feeding the homeless, and excoriated him for folding T-shirts instead. She urged him to take “etiquette classes.”

Mill is uniquely situated to effect change. And, though his case may be over, so are we—by looking at the overreaching of his judge and asking how we can stop abuses from happening to others who also don’t have a voice.

Any fair-minded viewer of Free Meek can only conclude that Brinkley confuses justice with control. When she says to Mill, after her bizarre visit to Broad Street Ministries, “It was only when you realized that I came there to check on you that you decided to serve meals,” that is all about her ego. Or how about this: “I gave you break after break, and you basically just thumbed your nose at this court,” she told Mill. When she sentenced him to state prison, she said: “Then I’ll be done with you.”

Sounds more like a jilted lover than an attempt to rid civil society of a menace, doesn’t it? Which begs the question: How many other young African-American men are confronted by just such a justice system, men who don’t have Jay-Z or a billionaire like Michael Rubin available to them to turn their cases into movements?

“Brinkley is an example of what’s come to be called ‘Black Robe Fever,’” says Isaac Solotaroff, an executive producer of Free Meek; his brother, Paul, wrote the Rolling Stone article that first documented the travesties of Mill’s case and serves as the doc’s de facto narrator. “Judges become intoxicated by their own power. Genece is hardly the only judge to act in such a capricious way. There are many other stories like hers and Meek’s around the country.”

How is it that there’s as yet no public consideration over Brinkley’s fitness to serve? Just recently, the Pennsylvania Judicial Conduct Review Board moved to suspend Common Pleas Court Judge Lyris Younge for an alleged pattern of civil rights violations and for her “impatient, discourteous, disrespectful, condescending, and undignified” demeanor while presiding over Family Court cases. Well, the same description could conceivably fit Brinkley’s conduct in the Mill case; yet, I’m told, the Review Board hasn’t acted on complaints against her because, unlike in Younge’s case, there’s no multi-case pattern of judicial intemperance.

That may be, but I challenge you to watch Free Meek or wade into the history of the Mill/Brinkley relationship and to not feel like you’re witnessing a miscarriage of justice—and this says nothing about the film’s work, thanks to two private investigators, in holding Mill’s original 2007 arrest up to inspection, sowing reasonable doubt as to whether it was legitimate, or orchestrated by corrupt cops.

Free Meek doesn’t go deep beyond the particulars of Mill’s own story, which is too bad. Because, in addition to Brinkley’s conduct and questionable judgment, there’s her complicity in a system that drives mass incarceration, which we rarely think of as an outgrowth of probation and parole. Pennsylvania has the nation’s highest number of citizens under that system—nearly three times the size of the incarcerated population. How many thousands of them are getting resentenced to prison time like Mill, not out of a concern for public safety, but because some judge felt dissed?

This is why Meek Mill’s next act promises to be so interesting—because, like Nixon going to China, he has the street cred to change behavior rather than perpetuate it. He and Rubin are to be lauded for seeking to emancipate one million people from the parole and probation system, but just getting guys out of prison isn’t real change. Providing opportunity to them, however, is.

A Harvard Kennedy School of Government report suggests the answer would seem to be plenty. In Less Is More: How Reducing Probation Populations Can Improve Outcomes, the authors argue that probation has not served as an alternative to incarceration so much as a driver of it. Perhaps a future project of Mill’s—now that, along with Rubin, he’s dedicating himself to criminal justice reform—is to introduce us to all of those he came across on the inside whose cause he now champions.

Which gets us to the reconsideration of Mill himself. In Free Meek, he comes off as thoughtful, straight-forward and ever-evolving. “Let me tell you something, that guy comes from a wonderful family,” Solotaroff says. “He was loved.” (When Solotaroff’s wife gave birth during the shooting, the Mill family showed up for him with four bags of baby clothes).

Indeed, in his recent work and in the doc, Mill, who says he read a lot of books while in prison, seems to be learning and growing, as in a scene in the recording studio, when he stops a track to lecture his producer on constitutional issues. “You know what the 13th Amendment is?” he asks. “If you under the state custody or federal custody, you allowed to be, what? A slave, a legal slave. Ain’t that crazy?”

“The change I’m seeing in my brother is almost scary,” Mill’s sister, Nasheema Williams, says in Free Meek. “I’m glad I’m seeing it, ‘cause this is the stuff I prayed for.”

Here’s hoping Mill’s newfound social consciousness and thoughtfulness consistently finds its way into his work. Back at the dawn of rap music, I remember being on the New York City subway and seeing legions of young African-American men furiously scribbling rhymes in tattered notebooks. It was the birth of a new literary form. When NWA rhymed “my full capabilities” with “correctional facilities” in Express Yourself, and when Public Enemy’s Chuck D said that rap music was “the CNN of the ghetto,” it signified that rap was becoming more than a passing fad. Something culturally significant was afoot, and, if you cared about civil society, you ignored the messages of hope, love, anger and celebration coming out of hip hop nation at your peril.

Mill may finally be in the clear, but the documentary stands as an indictment of a broken system. It raises serious concerns about just how much justice there is in our criminal justice system, particularly for the powerless.

But—and here’s where I may be slipping into get off my lawn mode—something happened. Spike Lee called it “the new minstrelsy;” in our free market worship, the socially conscious raps of MC’s like KRS-One and Mos’ Def ultimately took a backseat to the nihilistic glorification of Glock-fueled violence and misogyny. Instead of rappers offering honest, unflinching glimpses into street life—like Biggie Smalls’ perfect encapsulation of the lack of inner-city opportunity at the tail end of the Reagan era: You either slingin’ crack rock / Or you got a wicked jump shot—we got macho poses and narcissism run amok, without context. Mill’s work was a case in point, as in “Dreams and Nightmares,” the song the Eagles and Sixers use as they enter their fields of play:

No crawling, went straight to walkin’ with foreign cars in my garage / Got foreign bitches menaging, fuckin’, suckin’, and swallowin’ /

Anything for a dollar, they tell me get ‘em, I got ‘em…

I’m that real nigga what up, real nigga what up /

If you ain’t about that murder game then pussy nigga shut up /

Mill wasn’t alone. Rather than comment on and bemoan the conditions of inner-city life, it seemed a new generation celebrated rather than challenged the hardness and inhumanity of the streets. In last year’s Championships, his most recent album, Mill can still pander, as in “Stuck In My Ways”:

Too many bad bitches waiting in line/

That pussy good, I’ma take her to shine/

She lose a point, it’ll make her a nine/

She know I got some paper, I ain’t gotta pay her

But, more often than not since his release from prison, there are signs that Mill’s criminal justice journey has surfaced an awareness in him to move beyond the one-dimensional pose, as in the title track:

All the young’ns in my hood popping percs now/

Gettin’ high they get by, it’s gettin’ worse now/

Them jails got ten yards in ‘em and that’s your first down/

And I ain’t come here to preach/

I just had somethin’ to say ‘cause I’m the one with the reach

Now that Mill’s case has ended, now that his legal travails have made him more of a star than his rhymes ever had, now that he and Rubin have created a $50 million nonprofit to greatly reduce those caught up in the parole and probation system, now is when the Meek Mill story really gets interesting. Because you never know just who, owing to a mix of circumstances and internal fortitude, is going to step up.

“If, back in the ‘50s, I’d have told you that a Harlem pimp would become one of the most influential speakers and leaders of the 20th Century, you’d have laughed at me,” the political consultant Mustafa Rashed, who offers compelling context around Philadelphia’s deindustrialization and disinvestment in Free Meek, told me last week. “But that pimp went on to be Malcolm X. I’m not saying Meek is Malcolm X. But you listen to a song like “Oodles O’ Noodles Babies,” and you realize you never know who is going to become the person they become.”

How is it that there’s as yet no public consideration over Brinkley’s fitness to serve?

In one of Paul Solotaroff’s Rolling Stone interviews with Mill, the rapper showed just that propensity for growth. “If the police are already failing you and your community, and your community is failing you, and your own people are failing you, you will kick into survival mode,” he said. “I think that issue should be addressed. I can’t blame it just on police, because it’s a self-hatred issue, too, where we are killing one another, African Americans, and we’re also living in unsafe neighborhoods where you can’t walk to the Chinese store without thinking you’re gonna get killed.”

This is why Meek Mill’s next act promises to be so interesting—because, like Nixon going to China, he has the street cred to change behavior rather than perpetuate it. He and Rubin are to be lauded for seeking to emancipate one million people from the parole and probation system, but just getting guys out of prison isn’t real change. Providing opportunity to them, however, is. Maybe Mill starts telling the stories of those he met on the inside, creating a groundswell of empathy. Or maybe he and Rubin hire and train returning citizens to be entrepreneurs. Or maybe his rhymes are constructed to give inner-city kids something hopeful to say yes to, instead of just more gun-waving and acting out.

Mill is uniquely situated to effect change. And, though his case may be over, so are we—by looking at the overreaching of his judge and asking how we can stop abuses from happening to others who also don’t have a voice.

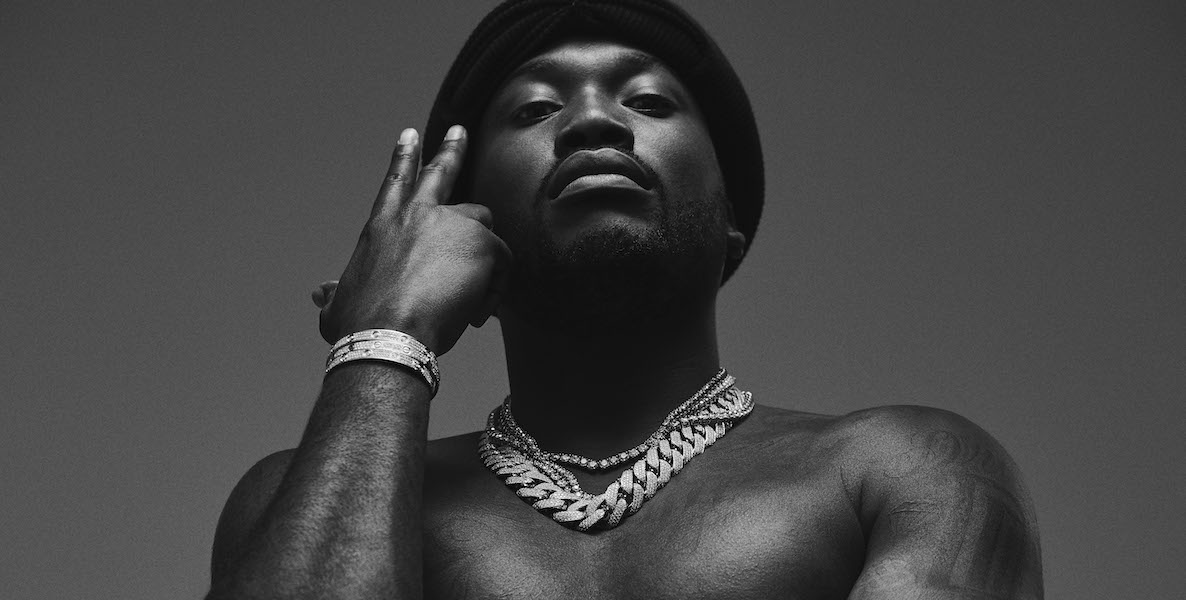

Photo courtesy Miller Mobley / Atlantic Records