Last week, the day after Seth Williams pled guilty to one count of bribery and resigned his office as District Attorney, I received a terse email from Herb Glickman, a brilliant, irascible retired New Jersey Superior Court Judge. It read: “What the hell is in your drinking water?”

Judge Glickman—or Herbie, as I’ve always known him, is my late father’s first cousin. During his 23 years on the bench, he’d earned a no-nonsense reputation. I gave him a call. “What is with you people?” he spat out, referring, I guess, to us Pennsylvanians, who have now seen the top law enforcement officers in our state and city, respectively, morph into convicted felons. “Where’s the outrage? Someone’s got to do something!”

The conversation went on—the esteemed jurist referred to his state’s governor as “that fat slob on the beach” during the holiday weekend’s contrived public beach shutdown—but I kept reflecting on Glickman’s question about us. Where is the outrage? Pundits and politicians shake their heads, mourning the fall of Williams, but there’s precious little anger or calls for reform. Last week, on Channel 6’s public affairs show Inside Story, attorney Val DiGiorgio, who heads the state GOP, proclaimed it a “sad day for Philadelphia,” and said he was “sorry for Seth, sorry for his kids.” Now, DiGiorgio and Williams were once classmates, so I get it—when it hits home, it’s hard not to be compassionate.

But, in the aftermath of seeing our District Attorney carted off to a federal holding cell in handcuffs until his October sentencing, I can’t tell you how many “poor Seth” conversations I’ve found myself in. What about compassion for the hard-working taxpayer? Respected defense lawyer Samuel Stretton, who last year amended the DA’s financial disclosure reports to reveal $164,000 in previously unreported gifts, told the Inquirer he was shocked that Williams was immediately taken into custody after pleading guilty: “I’m shocked that they didn’t work out a deal to keep him out on the street. That puts Seth Williams in a very dangerous situation. I’m a little taken back by that. He could have stayed out until his sentencing.”

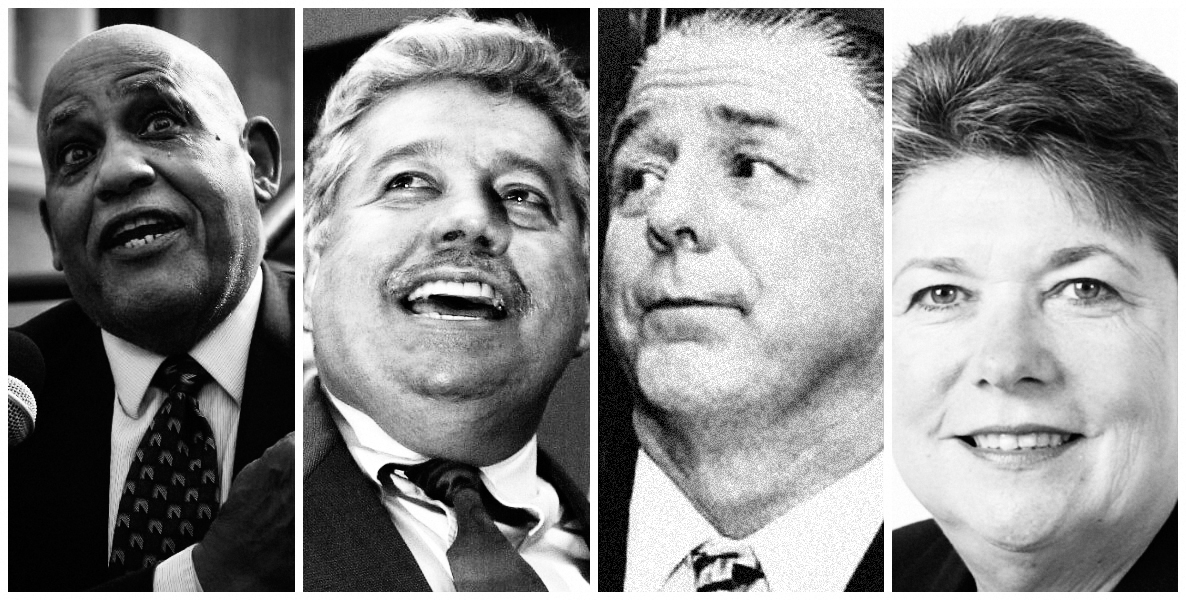

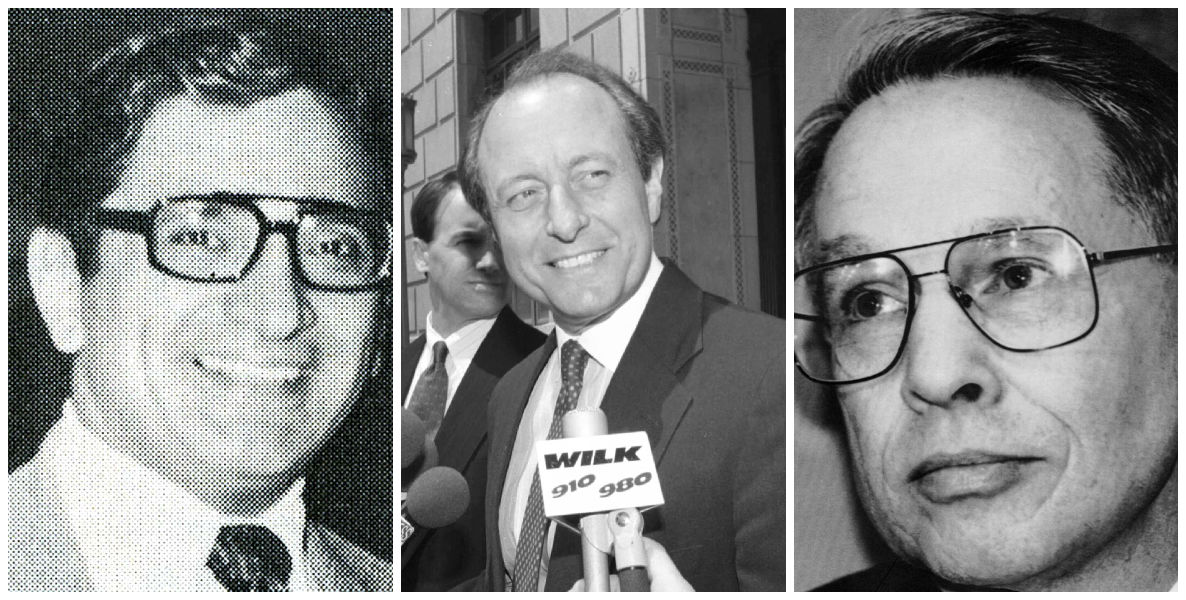

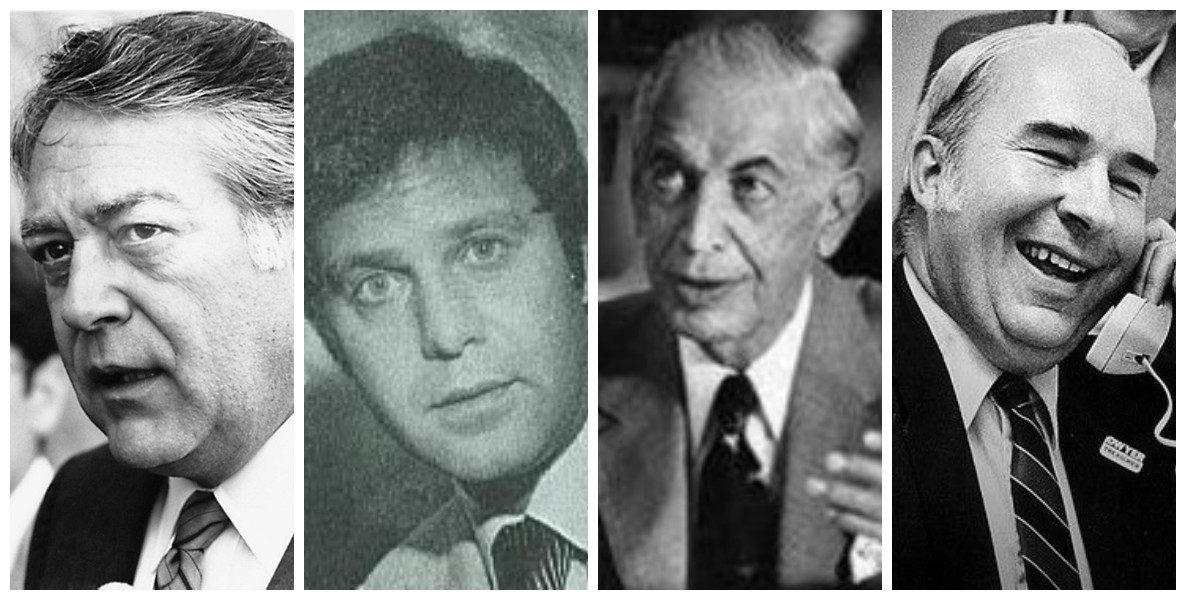

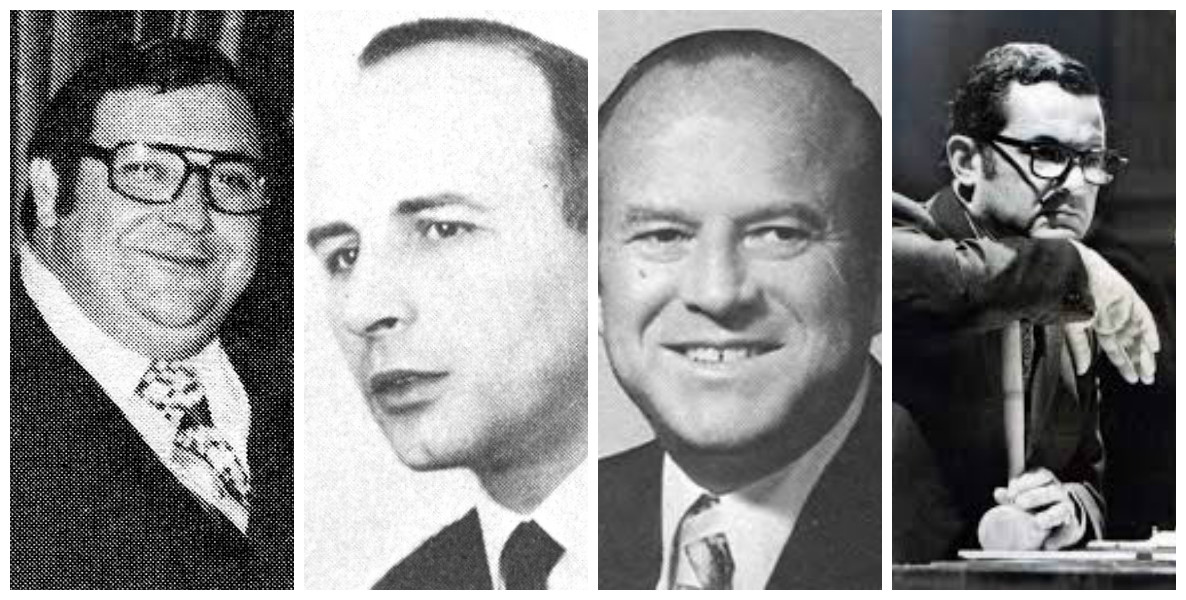

Shouldn’t our reaction be one of anger, not sadness for Williams? After all, the Williams case isn’t solely about Williams; it’s really about a culture of corruption we’ve allowed to take hold, over decades. Shouldn’t we be angry that there are so many cases of political corruption that I can’t list them all here? That the perp walk parade of Williams, Kane, McCord, Estey, Tartaglione, Fumo, Fattah et al is seen by a retired judge in Long Beach Island—and who knows how many others—as our story, as a referendum on us and our tolerance for con artists masquerading as political leaders? And that other political leaders—those who have not been indicted, or not yet—react with shoulder-shrugging soundbites?

“I wish he’d done it much, much sooner, but I’m glad for the employees of the DA’s Office and for the people of Philadelphia that it’s over,” Mayor Kenney said in a statement upon Williams’ resignation, prior to his plea. “Now we can finally move on to a new chapter.”

Shouldn’t our reaction be one of anger, not sadness for Williams? After all, the Williams case isn’t solely about Williams; it’s really about a culture of corruption we’ve allowed to take hold, over decades. Shouldn’t we be angry that there are so many cases of political corruption that I can’t list them all here?

Is that what we want to hear from our elected leader? Move on to a new chapter? How’s that been working for us? How about something like this instead: “For too long, elected officials in Philadelphia have betrayed the public trust and damaged the relationship between the government and governed. This is bigger than Seth Williams. We need to finally address our widespread culture of public corruption, which is why I’m announcing today a mayoral task force, comprised of citizens, public thinkers and policymakers, to hash out ways to address the problem.”

That’s what Judge Glickman was getting at: Someone’s got to do something. Of course, we know by now the answer is not solely to be found in policy prescriptions. in the past, I’ve married the litany of perp walks and ethical transgressions that dominate our headlines with innovations like the Netherlands Court of Audit, akin to our Congressional Budget Office, which tries to promote integrity in government rather than just punish corrupt politicians. Or there’s Transparency International, which publishes a Local Integrity Systems Assessment Toolkit that explains how they work with local governments and civic partners to bolster integrity. Most recently, a Nigerian Ministry of Finance program that offers public corruption whistleblowers between 2 and 5 percent of recovered ill-gotten funds has recovered some $180 million.

Maybe we just need to start by taking a cue from Judge Glickman and expressing moral outrage, thereby shaming those who make our city seem like a banana republic, where laws are met with winks and nods by a toxic mix of oligarchs and apparatchiks who feast at the public trough.

Which brings us to this story’s hero. The judge who had a teary-eyed Williams immediately carted off to federal detention seemed like he was channeling Glickman. U.S. District Judge Paul Diamond is a one-time law clerk of the venerable former Pennsylvania Supreme Court Justice Bruce Kauffman. Diamond was also once aligned with Arlen Specter, serving as treasurer and counsel for the then-U.S. Senator’s 1996 presidential campaign. In his courtroom last week, Diamond struck the same notes of moral rectitude we used to hear from Specter, a cut-and-dried view of right versus wrong that is too often in short supply these days:

“I have a guilty plea from the highest law enforcement officer in the city,” Diamond said. “He betrayed his office and he sold his office. I am appalled by the evidence that I have heard.”

By surprising everyone and sending Williams away without delay, Diamond was breaking precedent and, one suspects, sending a message. Yes, Fumo and Fattah were granted time to get their affairs in order before serving their sentences. But maybe the image of Williams cuffed and taken directly to prison will make the next tempted politician think twice?

“He didn’t kill anyone, for Christ’s sake,” legendary defense lawyer, and one-time prosecutor, Jack McMahon told the Inquirer after Diamond’s decree. “I don’t think it was necessary to jail him now, and to be honest, I thought it was harsh.”

Williams’ lawyer, Thomas Burke, chimed in: “Judge Diamond is who he is. It makes you wonder, though: Was [this decision] really about the nature of the defendant, or more about the nature of the judge?”

What Burke doesn’t say, but what he no doubt knows, is that all judicial rulings have something to do with the nature of the judge. And Diamond’s nature is to not suffer fools, whether they be highfalutin DAs with the chutzpah to argue that campaign funds are rightly spent on a Sporting Club membership because getting buff is critical to getting elected—seriously—or grandmas who commit decades of fraud.

By surprising everyone and sending Williams away without delay, Diamond was breaking precedent and, one suspects, sending a message. Yes, Fumo and Fattah were granted time to get their affairs in order before serving their sentences. But maybe the image of Williams cuffed and taken directly to prison will make the next tempted politician think twice?

Five years ago, Doris Whitfield Richardson, a 60-year-old wheelchair-bound defendant, came before Diamond. She had carried on a two-decade scheme to collect her late grandmother’s veterans’ survivor benefits in order to, she testified, care for two young adult grandchildren, one of whom was disabled. Let’s listen in:

Judge Diamond: Did it ever occur to you to go out and get a job?

Whitfield Richardson: I did want a job.

Judge Diamond: You stole close to a quarter of a million dollars. Did it ever occur to you that the way to help your grandchildren was not commit an endless series of federal frauds?

Whitfield Richardson: I see that now.

Judge Diamond: Now?

Whitfield Richardson: I see it. I didn’t see it that way.

Sentencing the wheelchair-bound grandmother to nearly three years in jail, Diamond ordered her taken into immediate custody. Seems to me Diamond is consistent, which is what we want from our jurists: His outrage toward Williams is on a par with his outrage toward Whitfield Richardson. You can make the argument, as many have, that in both cases, Diamond has been too unforgiving, too harsh. But his job is to punish those who break the social contract. In the end, the high-flying, jet-setting DA and the wheelchair-bound grandma were treated equally in Diamond’s courtroom; isn’t that what justice is all about?

Header Photo: Library of Congress