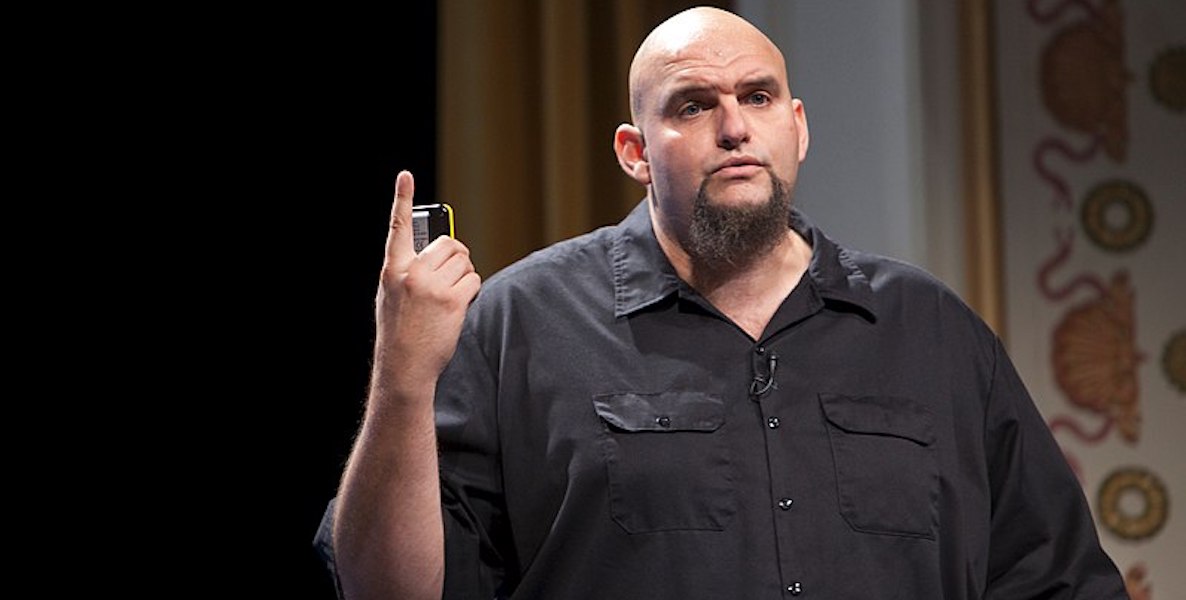

On the morning of October 27, 2018, the Republican candidate for Lieutenant Governor, Main Line businessman Jeff Bartos, was visiting his daughter at college when his phone rang. It was—oddly—his opponent, John Fetterman. What could he want?

Fetterman was calling with tragic news that had not yet been made public. There had been a mass shooting at Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life synagogue. “Brother, you were the first person I thought of,” Fetterman said, in a voice thick with emotion. “I’m so sorry there is such a sickness in our country.”

Join our virtual event with Fetterman and BartosDo Something

In short order, they became a type of political odd couple, their close relationship a testament to the quaint idea that, in politics, you can disagree without being disagreeable, and that, when you know a rival—really know them—it enhances the likelihood of finding common ground.

They’ve broken bread together with their spouses— after the first time John and Gisele came over for dinner, Bartos’ wife Sheryl said, “They’re lovely. Why don’t we meet more people like them in politics?”—and their kids have gotten to know one another.

“Jeff is just a really good dude,” Fetterman says.

“John is a mensch,” Bartos says, referencing an event at Pennsylvania Society just after Fetterman had won their election, at which the lieutenant governor-elect agreed to speak on the condition that Bartos share the stage with him. “That’s who John is,” Bartos says. “Someone who shares the stage.”

He’s also someone who is trying to make a point: Maybe one answer to our corrosive politics can be found in the way our politicians relate to one another. When I ask Fetterman what the effect would be if all politicians had the type of authentic friendship he has with his vanquished rival, he makes it explicit.

“Stop rewarding fringe behavior and fringe ideas,” Fetterman says. “Demonizing gets rewarded. Voters have to reward problem-solving.”

“It would change everything,” he says. “You put Jeff and I in a room and we can figure out so much together. We know each other and we trust each other. The idea of binary politics is just silly. If you’re for X, you’re evil, and if you’re for Y, you’re pure. It’s the death of nuance. Put me and Jeff in the room and we’ll find common ground and solve problems.”

Even before the Tree of Life tragedy, the two men—outsiders, both—had defied the script for how rivals ought to behave toward one another at a time when politics has become blood sport.

After they’d both won their respective primaries, for example, they found themselves at the same rubber-chicken function, where tradition held that new rivals warily circle one another. Instead, Bartos sauntered up to Fetterman, extended his hand and not only introduced himself, but suggested they exchange cell phone numbers.

“After he walked away, I said to my aide, ‘Is he fucking with me?’” Fetterman recalls, laughing. “I thought he was trying to get in my head.”

Instead, a rare political bromance was born. The two began texting:

Where are you today?

Heading to Altoona. You?

Got a fundraiser in Philly.

Especially after Tree of Life, a deep bond had formed. “I’m proud of what we did together,” Fetterman says of their campaign, notable for the high-mindedness and mutual respect displayed in their televised debate.

Eight years ago, it actually made headlines when a member of Congress started hosting weekly Costco lasagna dinners for a group of five Democratic and five Republican colleagues.

“It’s a sign of the apocalypse that this is even news,” Democratic Rep. Peter Welch told me when I interviewed him about the dinners. Yes, he conceded, gerrymandering and a 24-hour news cycle that rewards loud over thoughtfulness have a lot to do with our polarization, but so does a very simple fact: Democrats and Republicans don’t hang out together. “The combat of politics has become a macho struggle,” Welch said. “That’s easy to do when you don’t know your opponent.”

That’s Fetterman’s thesis today, and Welch even provided a compelling case study of it. When Welch’s party was in the majority, he could have passed his Home Star energy efficiency bill with just the support of his fellow Democrats on the energy and commerce committee—as was customary. Instead, he visited every Republican member and ended up getting 12 GOP supporters, including Texas’ Joe Barton, who was aligned with big oil and questioned the validity of global warming science.

Ironically, when Welch first ran for the House in 2006 in environmentally-friendly Vermont, he used Barton as a bogeyman in his advertising—complete with the ominous, deep-throated warnings about the need to send Welch to Congress to oppose the likes of “Joe Barton from Texas.”

After the first time John and Gisele came over for dinner, Bartos’ wife Sheryl said, “They’re lovely. Why don’t we meet more people like them in politics?”

When Barton responded positively to Welch’s overture, it was an a-ha moment. “I’m never going to convince Joe Barton on global warming,” Welch said. “But after we found common ground on energy efficiency, I told him, ‘You know, it’s a good thing I didn’t know you before I ran for the House and used you in my ads. Because I kind of like you.’”

On Wednesday, September 9, when Fetterman and Bartos appear together for a Citizen Virtual Town Hall event that I’ll moderate, they’ll amuse and inspire with tales about their relationship, but they’ll also explore the ramifications of Welch’s political hangout cure.

And I’ll ask them the same question I asked of Fetterman: What can citizens do to encourage politicians to adopt the tenets of civility they’ve modeled for us?

As usual, Fetterman was ready. “Stop rewarding fringe behavior and fringe ideas,” he said. “Demonizing gets rewarded. Voters have to reward problem-solving.”