Last week, when the FBI and IRS were removing boxes of evidence from labor leader John Dougherty’s home and office, as well as the Council office of his longtime acolyte Bobby Henon, didn’t it feel like we’d seen this movie before? When it comes to our region and public corruption, it’s as if we’re all trapped in a type of Groundhog Day.

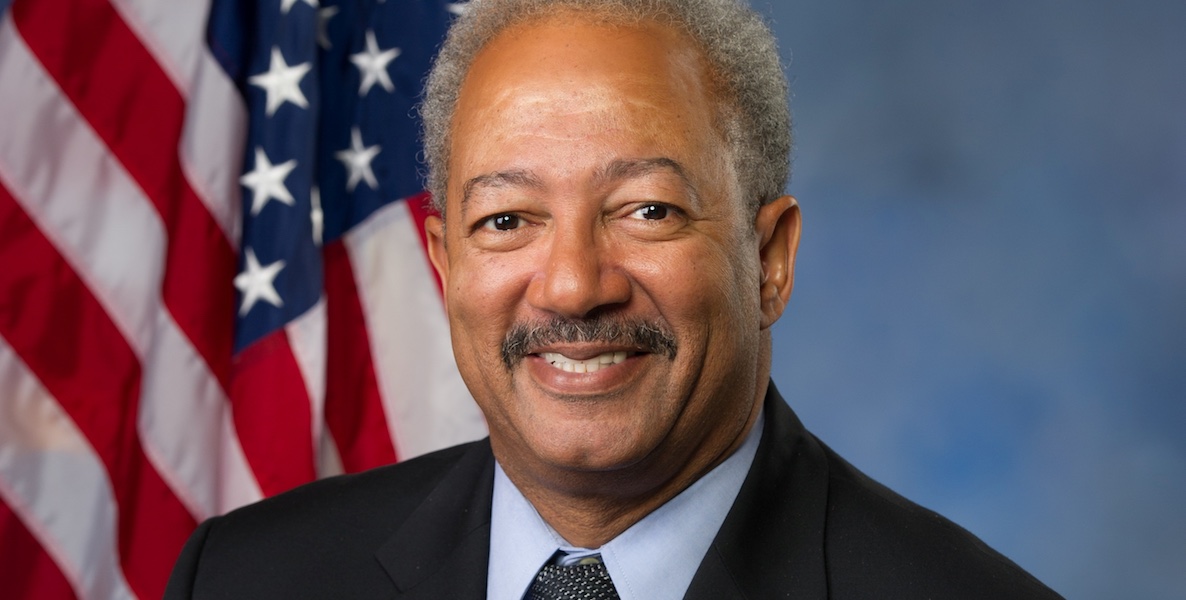

Let’s do a quick review. We’ve got two boldface names who, we now know, have long been wearing wires for the Feds—former Rendell Chief of Staff John Estey and former Treasurer Rob McCord—and we’ve got now former Congressman Chaka Fattah waiting to find out just where he’ll be going on a federally mandated vacation, and for how long. There have been the scandals at Traffic Court, leading to its abolishment. The “sting” of four Philly state House members. The statewide judicial porn scandal, featuring Supreme Court justices resigning in disgrace, and the wacky Kathleen Kane chronicles. There’s State Senator Larry Farnese, charged with bribery in, of all things, a ward election. Farnese holds the no-doubt cursed seat once held by Vince Fumo, before he “went away,” who succeeded the legendary charlatan Buddy Cianfrani, a colorful South Philly rogue who once, referring to the prosecutor investigating him, quipped, “If he can’t get me, what kind of investigator is he?” Ol’ Buddy went away for racketeering and bribery and then came right back to South Philly to run his ward.

Six years ago, into this culture of corruption came a new, unlikely gunslinger, U.S. Attorney Zane Memeger. When Memeger was appointed by President Obama in 2010, the book on him was that he was a steady hand, an apolitical choice. The Delaware native, a former prosecutor, was competent but didn’t project as a firebrand. Well, that was six years ago. It has since become apparent that Memeger has Philly and the state of Pennsylvania in his crosshairs, and that, though the 51-year-old may appear unassuming, you underestimate him at your peril. Think of it: If Memeger succeeds in taking down Dougherty, he will have in short order decimated two of the most powerful, and once seemingly insurmountable, families in the Philly constellation—Fattah’s and Doc’s.

If we’re really serious about taking on our cultural affinity for the political perp walk, let’s hire Transparency International to come audit us. They’ve published a “Local Integrity System Assessment Toolkit” that explains in great detail how they work with local governments and civic partners to identify and reform weak spots in governmental integrity.

Remember, the FBI went after Dougherty before, when now Congressman Pat Meehan occupied Memeger’s chair. Dougherty eluded prosecution, which only made him seem more powerful among insiders. At the time, many of them suspected that Dougherty was an FBI informant, particularly when Fumo—his one-time mentor, against whom he’d turned—went down. It’s immaterial whether Dougherty aided prosecutors or not; what was real was the perception that, owing to his armor of Teflon, the guy must have had friends in high places.

And so Dougherty, his mystique at its zenith, went about building his empire, with tentacles reaching into the Mayor’s office, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, City Council, and countless boards and commissions. But now comes Memeger, a competing archetype: The crusading lawman, intent on cleaning up his town. It’s a familiar model; across the country, countless politicians have used it to advance their political fortunes, including Eliot Spitzer in New York and Chris Christie in New Jersey.

That’s how we’ve always taken on municipal corruption, by countering rogue actors with super hero-like men of the law. But how’s that working out for us? Clearly, we need to punish those who, sworn to uphold the law, break it—as well as those who enable them. But maybe the Groundhog Day nature of this dance we do over public corruption—perp walk, charges, trial, rinse and repeat—has made the electorate cynical and paralyzed.

The evidence suggests that our litany of scandal has done little to deter future bad acts, despite the law enforcement actions. So maybe we ought to broaden our view about how we go about enforcing good government.

That’s what they’ve done at the Netherlands Court of Audit, which has had some success by consciously promoting integrity instead of just fighting corruption. By focusing on integrity in government, they take a pro-active, preventative approach. The Court of Audit—roughly akin to our Congressional Budget Office— analyzes governmental integrity through something called SAINT, (short for Self-Assessed Integrity), a risk analysis workshop that is both a diagnostic tool and a way to intervene and change governmental cultures. And they use geo-spatial information systems—GSIs—in the form of cool, interactive mapping to build transparency and take government out of the shadows, where corruption flourishes.

Some of the best work in taking on corrosive political cultures across the globe has been done by Transparency International, a coalition that fights corruption. They’ve developed data-checking software that can identify public projects susceptible to risks of fraud, conflicts of interest, and other irregularities. For example, they’ve culled the voluminous public procurement data sets of European Union countries and have devised software that searches for abnormal patterns such as exceptionally short bidding periods or unusual outcomes—no compete bids, for example, or bids repeatedly won by the same company.

51-year-old U.S. Attorney Zane Memeger may appear unassuming, but you underestimate him at your peril. Think of it: If Memeger succeeds in taking down Dougherty, he will have in short order decimated two of the most powerful, and once seemingly insurmountable, families in the Philly constellation—Fattah’s and Doc’s.

So here’s an idea I’ve raised before. If we’re really serious about taking on our cultural affinity for the political perp walk, let’s hire Transparency International to come audit us. They’ve published a “Local Integrity System Assessment Toolkit” that explains in great detail how they work with local governments and civic partners to identify and reform weak spots in governmental integrity.

Finally, we’ve just got to care more—you and me. This isn’t some abstract, academic concern. At a time when our schools, roads and bridges are all crumbling, it’s also about following the money. Some months ago, Citizen columnist Jeremy Nowak wrote about this issue and cited a study out of Indiana University and the University of Hong Kong that found that the average amount of corruption in Pennsylvania costs each resident of the Commonwealth some $1,300. If enough of us, when watching the news footage of another politician being indicted, see it for what it is—evidence of a reach into our pockets in the form of a de facto Corruption Tax—maybe then our resignation will be replaced by outrage and demands for change.

What’s clear is that just throwing our bad actors in jail is not enough to clean up our politics. It more often than not just makes room for a new crowd…doing the same old bad stuff. Yes, we should still punish those who break the law. But let’s also remake the political landscape by building up a culture of integrity—which, unfortunately, has become too quaint of a term.

Photo header: Flickr/gosheshe