If you didn’t know already, applications for nomination to the Philadelphia School Board are now due Friday, January 31.

You also probably didn’t know that deadline was extended by over a week—a sign that perhaps word of the nomination process, which happens automatically with a new mayoral term, didn’t really catch. Nor is it easy to find any information about the applications on the Board of Education’s website.

![]() Or, maybe you did know, but couldn’t possibly apply. Because how many people in Philly really can deal with the thankless hassle of leading a big city school district with an over $3 billion budget … without pay?

Or, maybe you did know, but couldn’t possibly apply. Because how many people in Philly really can deal with the thankless hassle of leading a big city school district with an over $3 billion budget … without pay?

Philadelphia and the Commonwealth as a whole seriously need to explore the question: Should school board members be (1) elected and (2) paid? Doing so may help us arrive closer to an answer on some of the beleaguered public school district’s most pressing needs and problems.

Understandably, city officials, the mayor and City Council president chief among them, may view the prospect of an elected school board as unruly, unwieldy and yet another political power headache in a city plagued by too many.

Keeping the school board appointed keeps it under the full control and supervision of City Hall, versus the unpredictable nature of a new class of competitive politician.

But, even as Mayor Kenney argued for “accountability” as his core reasoning for dissolving the state’s imposed School Reform Commission (SRC) in 2017, that didn’t settle the question of whom that board is accountable to.

It is expected that most of the current board members will be reappointed by Mayor Kenney, except for Wayne Walker, one of the few members with experience in turning around and managing both corporations and nonprofits, who announced he’ll be stepping down.

New board applications will be considered by the 13-member Education Nominating Panel, consisting of a mix of educators, business and nonprofit leaders.

After tomorrow’s deadline, they’ll send recommendations for the board to the mayor, who will have final say on who’s appointed.

However, the parents and students who are most exposed to the bruising daily realities of the public school system get very little say in how it operates. This is unless they’re lucky enough (or, who knows, networked enough) to find themselves selected to serve on the 13-member Parent Advisory Council or as the two “non-voting” Student Members.

Otherwise, they can just show up vexed at the next school board meeting, yelling and pointing fingers at board members and the superintendent all night.

Still, that’s not exactly a productive family-district relationship.

Compared to the 10 largest urban school districts in the United States, Philadelphia is in the minority: one of four districts without an elected school board or the 40 percent of big metro school districts that rely on appointments by the mayor.

The other three large districts without elected boards are New York (which switched over to appointments in 2002), Chicago (where there is massive pressure to have an elected school board) and Houston.

Indeed, 90 percent of school boards throughout the nation are elected, which makes Philly’s public schools a big city, big district outlier.

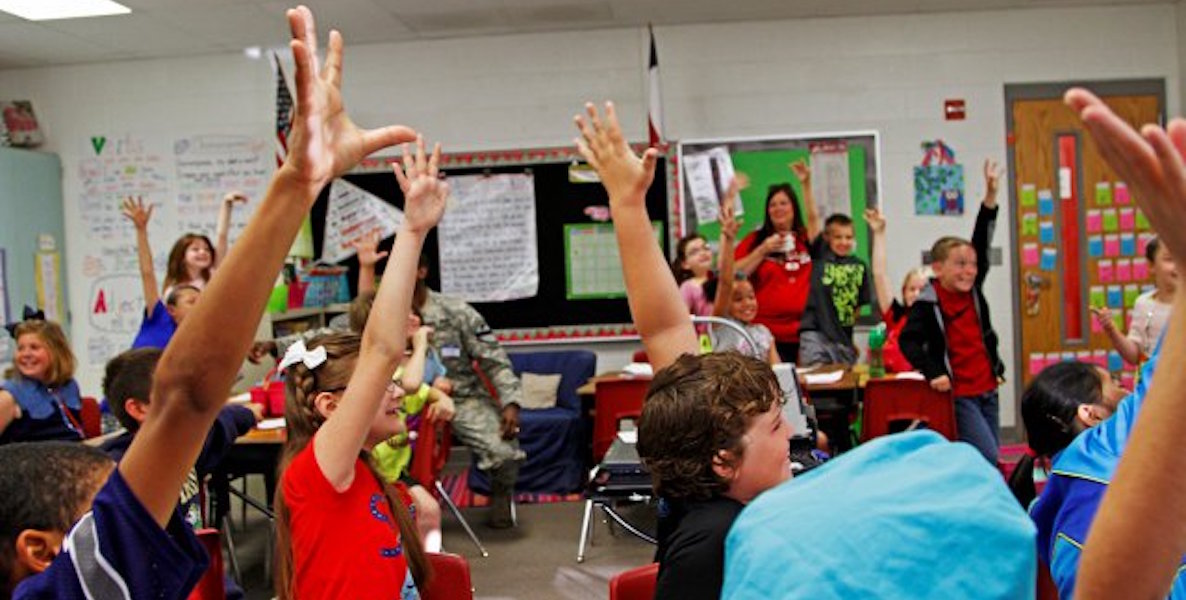

![]() The lack of an elected school board, and the demographic composition of the current Philadelphia School Board—along with how the dismantled SRC looked—could also explain the lack of urgent response and advocacy on major issues such as the ongoing school building toxicity crisis. It’s their official problem, but how personal of a problem is it to them?

The lack of an elected school board, and the demographic composition of the current Philadelphia School Board—along with how the dismantled SRC looked—could also explain the lack of urgent response and advocacy on major issues such as the ongoing school building toxicity crisis. It’s their official problem, but how personal of a problem is it to them?

In some ways, the board does reflect the district it serves: Racially, it’s mixed. Four out of the nine are current public school parents or activists; most are educators or work in social services; two are holdovers from the SRC. A couple have business backgrounds, including Walker. But they are also a highly educated and elite group.

Collectively, how much are those members intimately connected to the brutal day-to-day struggles of Philly’s largely low-income parent and student population? And how many of them have the expertise to oversee a $3 billion organization, or to navigate the politics and emotions rife with anything to do with urban public schools?

Probably not many.

And why would they be? How much time and energy can school board members commit to a job that’s unpaid?

Unfortunately, the dilemma in Pennsylvania is that while most major school districts in the Commonwealth are by election, state law prohibits paid board seats. It’s one of only three states, including Texas and Colorado, to do so.

Similar to the state’s gun-friendly laws impeding the city’s inability to pass its own gun legislation, that could also be an explanation for why district problems, which mostly impact economically vulnerable students, naturally receive low-energy attention.

There’s little incentive after hours of grueling committee meetings and, sometimes, contentious forums facing angry parents.

Only those who can afford to do it are the ones in a position to serve on the Philly School Board. Hence, the school district and student families miss out on the passionate insights of a person or two living modestly on Philly’s median income levels or lower, those who are confined to regular day jobs offering little flexibility for a parent who really wants to overhaul the school system the way it should be.

On average, at least according to a 2010 Fordham Institute survey of board members representing over 400 school districts in the U.S., 40 percent of board members spent more than 10 hours per week on school district business—in districts containing at least 15,000 students. That’s just a fraction of Philly’s size.

It would seem reasonable to expect a paid position for a system as large (200,000 students, 214 buildings) and complex as Philly’s. Even affluent Florida school districts with slightly smaller student populations, Orange County and Palm Beach County, have elected school board members who are paid, on average, a nearly $43,000 annual salary.

Los Angeles Unified School District board members receive an impressive $125,000 annual salary after a 175-percent pay raise in 2017 (whether that’s deserved or earned is another question L.A. will have to sort out).

Brookings’ Elizabeth Mann Levesque raised this question of paid versus unpaid school board positions shortly after much noise was made over the L.A. Unified School District raise.

“The lack of pay (or minimal pay) may mean that only those who have the means to support themselves otherwise have the time and financial resources to serve in this position,” she notes. “If so, the pay structure of local districts may be a barrier to entry for lower-income individuals, with clear implications for minority group representation. Nonexistent or uncompetitive pay may mean that many well-qualified individuals never consider this type of position, choosing instead careers where their skills will be adequately compensated.”

![]() Even though Philadelphia’s school board shows plenty of diversity by face, it isn’t fully representative of the population or of what’s needed.

Even though Philadelphia’s school board shows plenty of diversity by face, it isn’t fully representative of the population or of what’s needed.

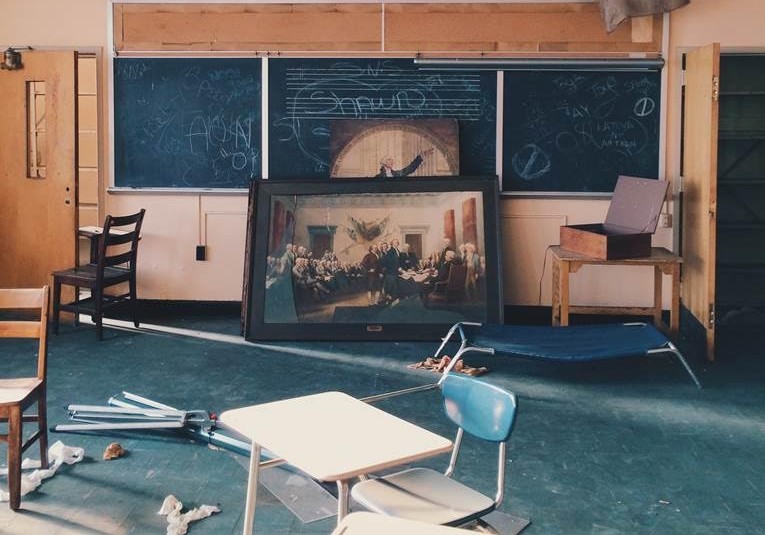

It goes without saying that the Philadelphia public school system has long been in desperate need of an overhaul. To do so means the inclusion of voices on the board who see that need from very ugly front lines each day—and from those with the experience to run businesses with the efficiency needed to solve systemic problems.

It’s not clear these current voices, or the ones waiting on appointment for the next term, really do.

Header photo courtesy Emma Lee