This past winter, I found myself locked in a staring match with a dragon fruit at the Acme. Cold winds had flushed my face, and here I was considering purchasing a tropical, Central American treat. This wasn’t the first moment — and certainly wouldn’t be the last — that I thought about how far food had to travel from farm to my stomach. That dragon fruit was the opposite of local.

But what is local food? The FDA defines it as food grown or raised within 400 miles of its vendor. You know what’s 400 miles from Philadelphia? Montreal, Canada. I don’t know about you, but I don’t consider somewhere I need a passport to go to be … local. To me, local means the state I’m in or the ones it shares a border with.

However you define it, the benefits of eating local food are clear: It’s better for the earth — cutting down on transportation, packaging — better for the local economy — supporting local farmers, makers and vendors — more transparent with opportunities to occasionally have face-to-face conversations with the person who produced my food and better for me, since it’s made without multi-syllable ingredients from who-knows-where.

“When you’re going to a farmers market, for the most part, you’re picking up ingredients. It takes someone willing to cook and prepare ingredients. You have to make it part of your routine.” — Alyssa Thayer, The Food Trust

So I set myself up for a challenge: for five days, eat exclusively locally produced foods. “It’ll be a walk in the park,” I smugly proclaimed to those invested in my journey. I’m from and now live only 12 miles from New Jersey — the Garden State — chock a block with farms. I have PA and DE at my disposal, and practically every neighborhood in Philly has its own farmers market, including one two blocks from my apartment.

Plus, I’m an eat-anything-except-for-fish kind of gal. If it was local, I could eat it. An easy week of eating and I get to call it “work?” Score.

Wrong.

Lesson learned the hard way: Local is way easier imagined than achieved. But with some planning, a flexible grocery budget, and a lot of compromises, it was … doable and mostly more delicious than what I usually eat.

“When you are eating local, what people often will trade is convenience,” says Alyssa Thayer, senior associate of the farmers market program at The Food Trust. “When you’re going to a farmers market, for the most part, you’re picking up ingredients. It takes someone willing to cook and prepare ingredients. You have to make it part of your routine. Life gets busy, so there’s a bit of intentionality that folks have to have.”

The game plan:

First, I decided on my firm rules and where I could make concessions.

Firm rule number one: All of my meal’s main ingredients had to be from PA, DE or NJ. If I was short one ingredient, there would be no quick trip to the bodega to grab it. Either it’s local, or I don’t eat it.

Firm rule number two: No eating out. Unless I make it myself, I can’t be 100 percent certain all of the food I eat comes from the tri-state area.

Concession: except for seasonings. I simply could not subject myself to a week of bland food.

So, I committed to flexibility — cooking based on the ingredients, not my cravings.

Shopping would start at my local farmers market, then maybe a few more working farms. Hopefully, I’d only need to make one or two more stops than I usually take during my weekly grocery jaunts. Wrong again.

Shopping for local food

First stop: Manayunk’s Saturday farmers market in Pretzel Park. The only vendor selling locally grown goods the day I went was Chester County’s Walnut Run Farm, vending their own and other local pesticide-, chemical- and artificial growth hormone free produce, dairy, meat and baked goods. I snagged goat milk yogurt and cheese, bacon, tomatoes, lettuce, einkorn tortillas and buns, chicken breasts, ground beef and sausage for $118 — a sum that far exceeds what I’d usually pay for 10-ish items.

But aside from Walnut Run Farm, the Pretzel Park Farmers Market has mostly local craft and specialty food (think artisan wine and fancy meatballs). So, I drove to Linvilla Orchards in Media to pick up some supplemental items. Though they may be better known for their seasonal amusements, Linvilla has a wide array of local food. I grabbed eggs, honey, asparagus, carrots, rhubarb and cucumbers ($30).

That still wasn’t everything I needed, so off I went to Bucks County to Renninger’s for strawberries, mint, zucchini and potatoes ($23) and circled back around to Philly for a pit stop at Iovine Brothers in the Reading Terminal Market, where I was surprised to see the only local goods (at the time) was whole wheat pasta and flour from Castle Valley Mill in Doylestown.

Never before in the history of purchasing my groceries had I spent this much on a week’s worth of food — or went to such lengths to obtain it.

On a desperate search for my last two grocery list items, heavy cream and a can of crushed tomatoes, I bounced from store to store growing increasingly more frustrated when I came up short. This included: my Acme, because I thought all Lucerne dairy products were local (they’re not), Ardmore Farmers Market where I grabbed nearly expired milk (I was desperate), Trader Joe’s which provided me with my crushed NJ tomatoes and, Whole Foods where I found my heavy cream. Later in the week, I made a stop at the Mariposa co-op on Baltimore Avenue and purchased some local hummus because after a week of cooking only local, hummus made by someone else felt like a novelty.

My bill for the five days: $228.50. Miles traveled: 77.7.

Never before in the history of purchasing my groceries had I spent this much on a week’s worth of food — or went to such lengths to obtain it. My two-person household typically budgets $80 for ingredients and another $80 for meals out, mostly quick trips to the deli.

If I spent $230 a week on food, my monthly grocery would be nearly $1,000. As someone who has student loans to pay and hopes to purchase a house in the coming years, that amount of money not only feels extravagant but also fiscally irresponsible.

For cost, Thayer reminds me, “There is a certain value proposition that you’re buying into when you’re getting local fresh food. You are paying for the quality and you’re buying into taste. [The food] is not traveling as far, which means it’s freshest and has the most nutrients, but it also means it hasn’t used a ton of huge carbon footprint to go where it needs to go.”

Finally to the fun part: Eating

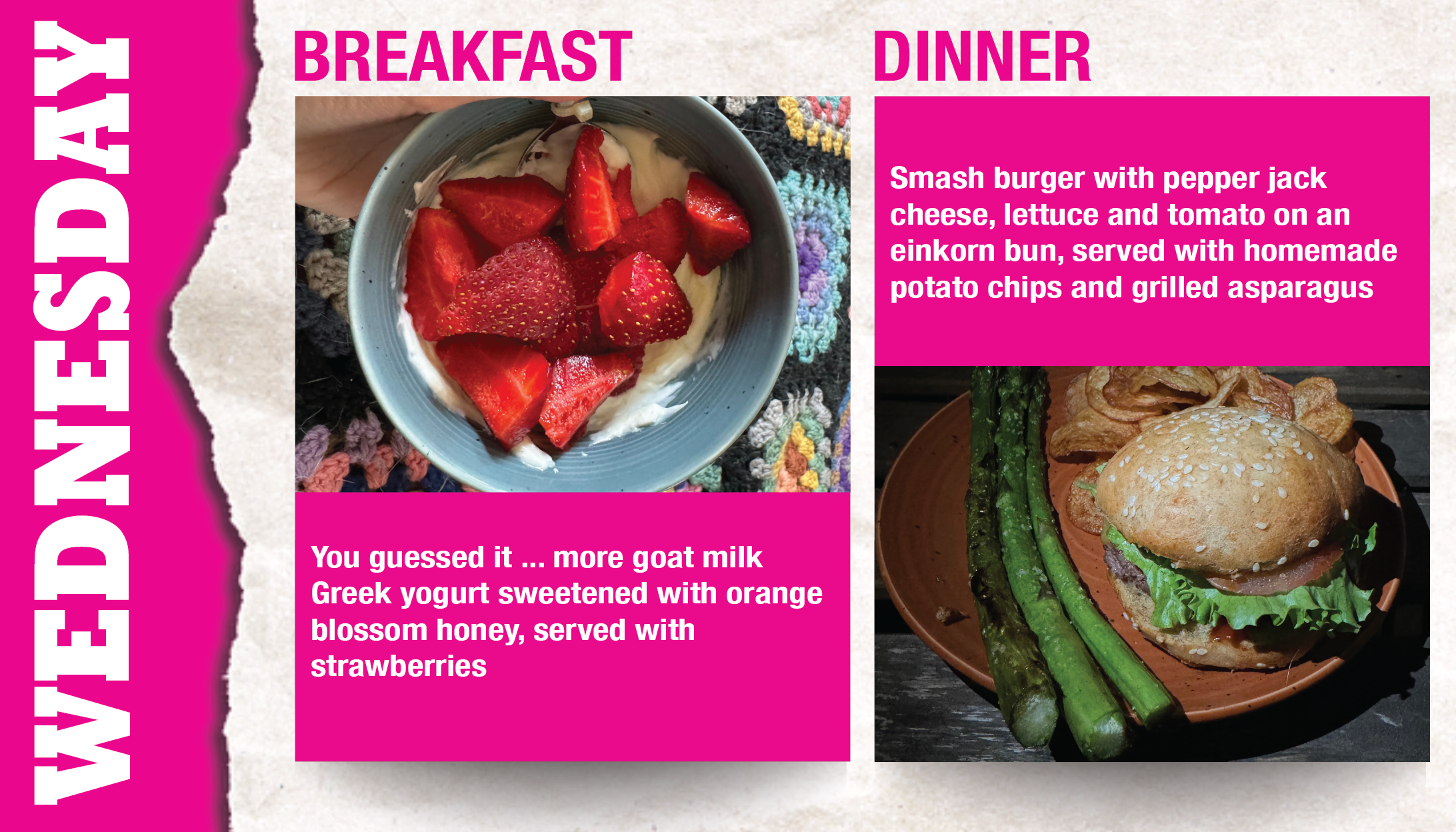

Day one was a dream, as I romanticized my life cooking the freshest of food like I was some sort of cool European living in the countryside. Brunch was luxurious with Greek yogurt so creamy and delicious that it tasted like ice cream. For dinner, I made my parents spicy Italian sausage ragú. They raved about it — and not just because they are my parents. It was delicious.

From there, results were mixed. That first day I spent twice as long in the kitchen as I usually do and lost stamina quickly. Romanticizing your life can only get you so far when you have real world things to do like taking your cat to the vet and making it to a meeting on time.

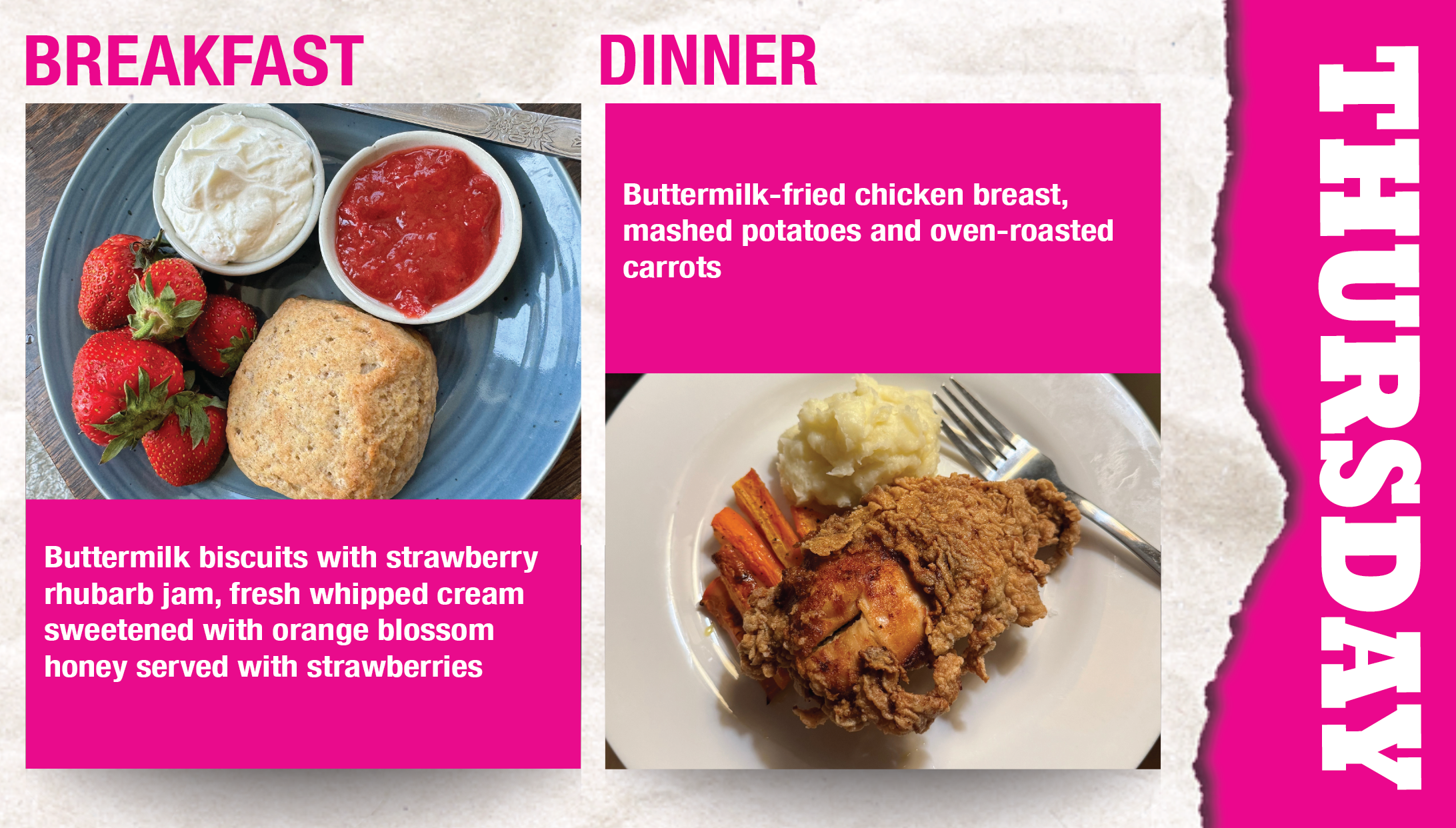

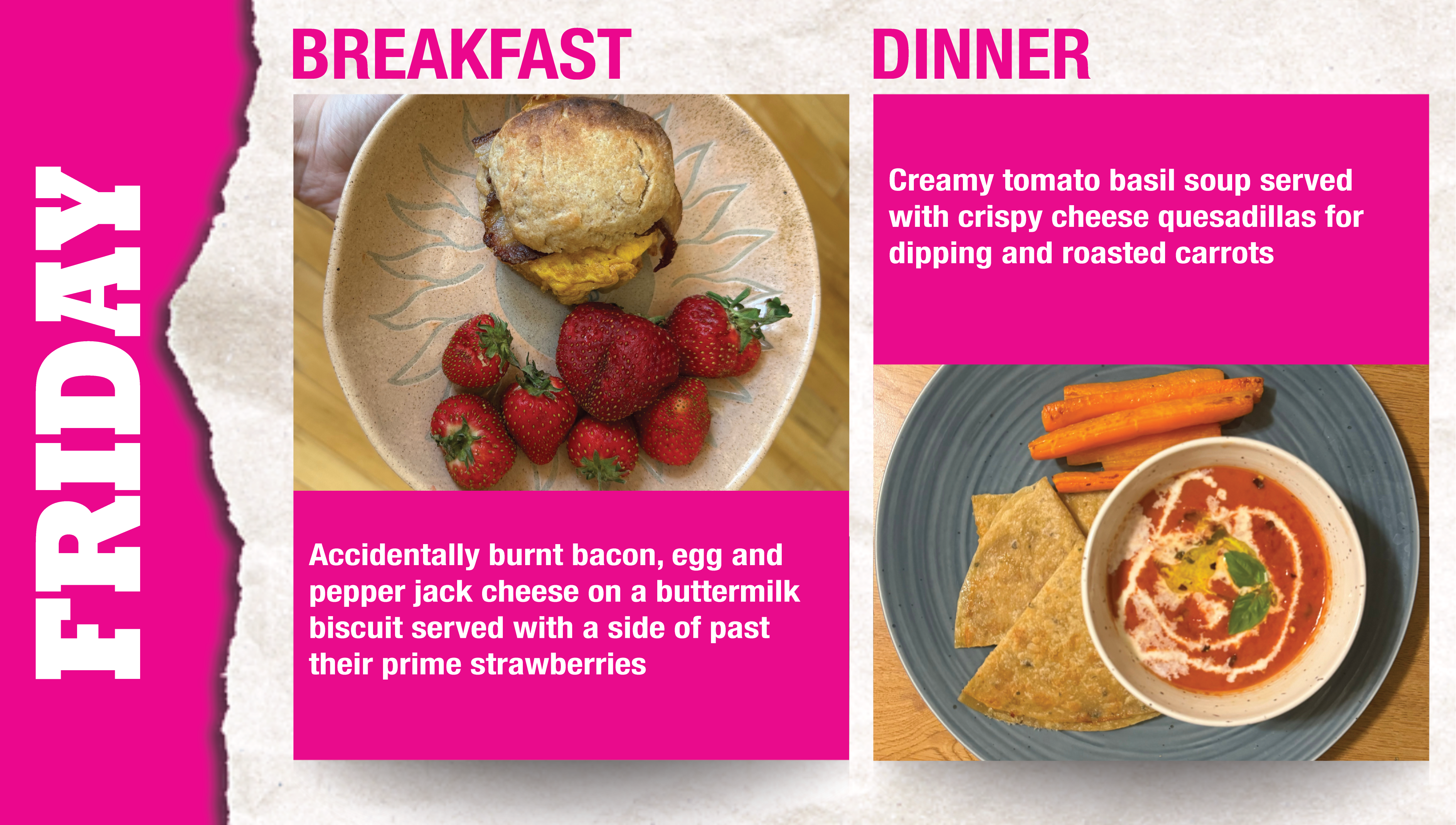

Breakfast burritos and chicken quesadillas with those einkorn tortillas tasted boring — no pico, no avocado, no hot sauce. Cheeseburgers, however, made with that expensive ($10 extra) ground beef, were a hit. Homemade potato chips didn’t quite satisfy the Herr’s craving but worked in a pinch. Homemade biscuits made with that Doylestown flour were sensational for one day and then disgusting the next (they went stale almost immediately). Also: Fresh strawberries go mushy fast.

By the end of the week, I was so exhausted that I ate my last meal with such little enthusiasm you would have thought it was gruel and not delicious tomato soup.

During this challenge, I nursed a virus — not easy to do when you can’t eat bananas, crackers or rice. Plus, my cat had a medical emergency which meant a late night at the ER, after which I couldn’t come home and order takeout and instead spent an hour cooking myself dinner at midnight. Food doesn’t always have to be convenient, but in these extenuating circumstances, it doesn’t hurt.

It wasn’t just the extra time. It was the anxiety, the worry about where my food would come from and if I would be able to put a meal on the table. I felt defeated by this challenge; it deflated my ego and wore out my love of cooking.

Could I eat only local food every day?

Well, I could if I had an unlimited budget of time and money. But as a 30-year-old that has more pressing financial responsibilities and a busy schedule, I just can’t swing eating exclusively local. I have too much going on to have my life revolve around shopping for and preparing food, and I can’t justify spending 1.5 times more on groceries a year.

But here’s the little dose of reality I should have forced myself to swallow when I started to spiral over a dragon fruit: It doesn’t need to be all or nothing.

I can afford to add a little more cushion to my weekly spend to make sure my meals include more local food. Especially if I cut down on my trips to the deli. And I can make sure I budget time every week to make one stop at a local food vendor.

Incorporating local foods is still worth it. You can still support local farmers and eat better without cutting out Acme entirely.

Since ending my eating local challenge, I’ve made a weekly stop at my neighborhood farmers market. Setting my budget around $50 usually gets me a few servings of vegetables, a package of fruit, yogurt and one or two packages of meat, depending on the price. I’ve continued to eat around my farmers market finds and not just my cravings.

Incorporating local foods is still worth it. You can still support local farmers and eat better without cutting out Acme entirely.

I can extend the longevity of my produce through canning or freezing to make it through the winter, but I may not need to. We’re fortunate in Philly that fruits and vegetables grow nearby every month. I can expand my meal repertoire by leaning into the seasonality of our region’s produce.

Thayer points out that most farmers markets have rotating vendors, so a savvy shopper should look at what’s coming up the pipeline and plan to purchase things like flour in bulk when the opportunity arises.

As for saving money, she suggested swapping out pricier items for more affordable comparable options. Don’t have money for two pounds of ground beef for your tacos? Get one pound and supplement the protein with black beans. Or ask your local vendor if they sell “seconds” — produce that is cosmetically imperfect or slightly passed its prime. Thayer says farmers will often sell these items at discounted rates.

And make sure to have a preservation technique locked and loaded.

“Even if it’s just freezing things or making a batch of something,” says Thayer. “The quickest way people get turned off is if they get more than they can use and it ends up going in the trash.”

Once I removed the challenge constraints, I loved cooking again and found that eating local can still feel romantic — and attainable. Now I approach eating locally with long-term enthusiasm rather than anxiety about how I’ll produce my next meal.

For others looking to try more local foods, Thayer suggests “Start with what you know and push yourself out of your comfort zone a little at a time to try new recipes. You don’t need to get six bushels of something right off the bat. Try it out. Then come back for more.”

Sounds like a plan.

![]() MORE ON PHILLY FOOD AND EATING FRESH FROM THE CITIZEN

MORE ON PHILLY FOOD AND EATING FRESH FROM THE CITIZEN