Dune fans were excited to hear on Friday, April 5 (also Happy First Contact Day to those who celebrate) that Legendary Pictures and director Denis Villeneuve are in development on Dune Messiah, the second novel in Frank Herbert’s seminal science fiction series, and what would be the third film for Villeneuve’s treatment of the Dune saga.

When placing Philadelphia in the Dune universe, even the most casual fans know that director David Lynch — whose 1984 critical and commercial disaster-turned-cult-classic-adaptation Dune was so painful for him to make that it was released under the direction of Alan Smithee — is a Pennsylvania Academe of the Fine Arts alum. Of his time in Philly in the late 1960s, he’s quoted as saying, “The biggest inspiration of my life was the city of Philadelphia.”

High praise.

But as it turns out, our city played an even more significant role in the launching of Frank Herbert’s masterwork into our collective consciousness. You could even say, we are the reason it even exists.

Did you have a Chilton auto repair manual?

My parents didn’t have an opportunity to purchase a new car until I was about 14. In our garage was a shelf lined with a distinctive set of tall textbook-like paperback books, black with color-coded labeling for make and block-print letters indicating the model. These were Chilton auto repair manuals, for my dad to do his own work on his Pontiac Manza, the 1984 Ford Escort hatchback, or the 1967 Ford F100 (and eventually, my own 1987 Dodge Daytona).

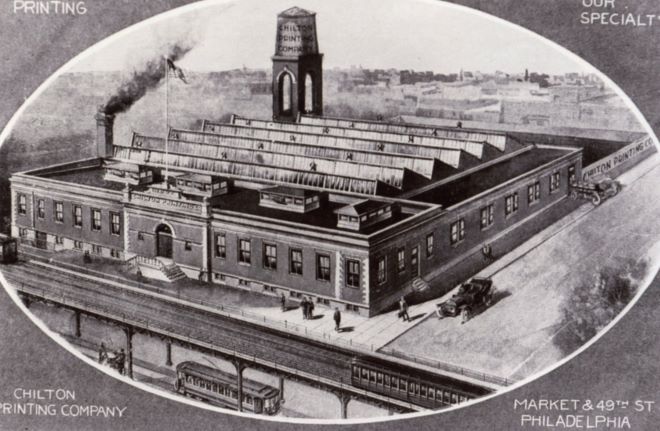

The Chilton Company was officially established in 1904 when George Buzby and C. A. Musselman, advertising professionals, and James Artman, an editor, who together had produced several iterations of a cycling and automotive trade magazine, formed a trade publishing and advertising company focused on automotive catalogs, booklets, circulars, and posters. The name Chilton reportedly was chosen from the Mayflower passenger list. It operated a printing plant at 49th and Market Streets right here in Philadelphia.

In 1923, the partners sold Chilton to a New York publishing company and opened a new printing plant at 56th and Chestnut streets, which would eventually serve as Chilton’s corporate headquarters. Then, in 1958, the company purchased Greenburg, a small trade publisher, and an editor named Sterling Lanier at Chilton began looking for a way to branch out into fiction with an original work.

Herbert, who was a journalist (among other things) before he was a famous author, was inspired to write Dune while covering the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s work on protecting beach dunes along the Oregon coast. It was not his first novel, but he had had limited success as a fiction writer so far. Diving into desert ecology and the cultures that arose in those environments — particularly Islam — and weaving in the politics of oil and environmentalism, he wrote a science-fiction messianic tale of woe that spans galaxies tens of thousands of years in humanity’s future. (Weird fact: There are no intelligent aliens in the Dune universe. It’s just humans and every planet’s unique fauna.)

Much like the Beatles’ early failed audition and Steven Speilberg’s multiple rejections from film school, Herbert sent Dune to 20 publishers who all turned the manuscript down. He managed to get it published serially in Analog, a science fiction magazine, in 1963-64. This caught the attention of Lanier, a sci-fi buff himself.

Chilton in 1965 finally published Dune. Lanier was subsequently fired due to poor sales.

To be fair, Chilton was charging $5.95 per copy, which translates to nearly $60 today. Dune won the Hugo Award (sci-fi literature’s highest honor) that year and went on to become an international bestseller that has been translated into 20 languages and spawned five more sequels, video and tabletop games, comics, a cable miniseries, and three films (so far). Herbert passed away in 1986, before he could reportedly finish more novels in the series. Since then his son, Brian Herbert, and writing partner Kevin J Anderson, have expanded the literary universe with prequels and sequels.

If you want to pick up that first edition copy from Chilton, make sure you have around $20,000-30,000 handy since the company only bothered to print about 2,200 of them.

So … what happened to Chilton?

In 1972, Philadelphia native William A. Barbour was elected president of the company after G. C. Buzby, son of co-founder George Buzby, retired. The headquarters were moved to Radnor that same year. In 1984, the plant on Chestnut closed operations. Chilton was bought by ABC in 1979 and thus came under the umbrella of the Walt Disney Company in 1996. Disney would split the company’s various publishing and advertising divisions among four other companies to reduce its debt.

In 2001, Nichols Publishing, which had acquired Chilton’s automotive brand publishing arm from Disney, sold it to Haynes, Chilton’s direct competitor. (How awkward.) By early 2022, Chilton’s online DIY auto repair library closed, and although you can purchase fresh print copies for models as late as 2017, your mid-life crisis repair manual will most likely be found on eBay.

Today, at 56th and Chestnut Street, there’s a medical building and a parking lot. Where the older printing plant stood on Market Street, there’s a Forman Mills clothing store.

It’s too early to know if Dune Messiah would require two installments like Villeneuve did with Dune, but we do know for sure that it would be his last Dune movie. For Duneheads, this isn’t too harsh a blow, because we know the third novel, Children of Dune, would be mandatory for the big screen once audiences experience the sequel, and thus fans would finally get what’s never been attempted before: a God Emperor of Dune film, because if there’s one thing we absolutely all want, it’s to watch a giant worm spouting political philosophy for three hours straight while Jason Mamoa facepalms in agony. (Don’t come at me about spoilers, ok, that book is nearly 40 years old.)

Meanwhile, this strange Philly publishing anomaly is not just a cool points-scorer at pub night trivia. It’s something we should shout from the dunes, i.e., high rises, or maybe with one of those blue state historical markers to indicate where one brave editor saw the future of science fiction way back in 1965.

Dune fans, you’re welcome.

![]() MORE AT THE INTERSECTION OF BOOKS, FILM, AND PHILLY

MORE AT THE INTERSECTION OF BOOKS, FILM, AND PHILLY