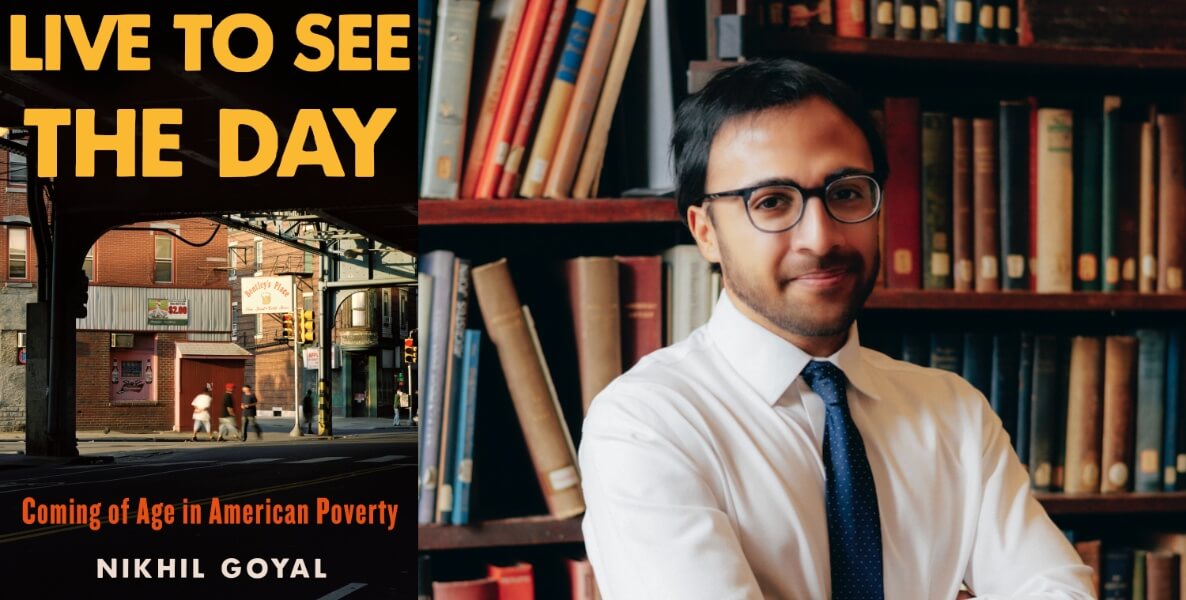

Editor’s note: This is an excerpt from Live to See the Day, a portrait of three children struggling to survive in the poorest neighborhood in Philadelphia. The author will read from and discuss the book at Headhouse Books tonight and at The Free Library on October 19.

Ryan Rivera hadn’t finished his first full year at El Centro de Estudiantes when Philadelphia’s school district announced that its 13 contracts with the city’s accelerated alternative schools, serving 1,800 students, were to be terminated. The disciplinary schools would also see their budgets cut. The district planned to move the accelerated programs to five regional centers that had “small class sizes, individualized learning plans, strong social supports, and project-based learning,” claiming the move would save tens of millions. It also intended to open 10 evening “twilight” programs at high schools with steep dropout rates. These moves would help the city plug a $629-million budget deficit.

When the staff at El Centro de Estudiantes [a Big Picture Learning school] broke the news to the students, there was little surprise. This is what they do to kids who look like us, they thought. Ryan was extremely upset. He had heard rumors about the schools shutting down but brushed them off as speculation. After the madness of Lowell, Grover Washington, and Community Education Partners, he had finally found a school where he was engaged and learning and loved going to every day, and he couldn’t believe they would take this community away from him. There was no backup plan, and based on his struggles to find an appropriate high school, he was sure the search for another one would be grueling.

Laura Shubilla, president and founder of the Philadelphia Youth Network, brought the heads of the schools together to build a strategy to stop the closures. With the help of Youth United for Change, an educational justice organization, students made posters and signs for the rallies and wrote letters. Ryan took an active role. He felt the school was worth defending with his time and sweat. He didn’t want to be forced to settle for a GED program or worse, drop out.

A moving letter by Matthew Prochnow, an advisor, described the school as a “place full of a familial type of love,” although a conflicted one, like any family. “It is a place where we have had to strive for love, and on some days we have had to fight, to claw and to scratch and to gnash our teeth for something even resembling love,” he wrote. “And even then, sometimes we have failed.” His students had long felt disempowered in their education and had rarely fought for better conditions in their previous schools. “They were accustomed to leaving and looking for something new,” he said.

“We don’t want our school closed.”

They had sat through more than five hours of testimony on the proposed reduction of full-day kindergarten to half day and on cuts to after school, summer, and other programs, and the El Centro de Estudiantes students were growing restless. As the crowd thinned, they moved from the mezzanine to the main level. It was a Wednesday evening in late May, and they were waiting to testify before the Philadelphia City Council in the hope of saving their school. The council chambers, built in the French Second Empire style, had a dazzling ornamental golden ceiling, a striking array of light fixtures, mahogany desks, and red carpeting.

When David Bromley, who was overseeing operations at the school as well as Big Picture Learning’s work in the city, finally stood up to testify, he framed the proposed elimination of the alternative schools through the lens of the families’ relationship with the district. “So what will happen if this proposal stands? One can only speculate but most likely many of these students, despite our best efforts, will not attend the proposed District-run learning centers and will drop out once more. There is a fundamental lack of trust between these students and families and the School District.” He was followed by more than a dozen students, staff, and parents.

“I can’t even call El Centro an alternative school. To me, an alternative school feels like a prison, but El Centro feels like home.” — Ryan Rivera

The mic was eventually passed to Ryan. Baby-faced with short-cropped black hair, he was dressed up in a white-and-navy plaid button-down shirt. He was anxious. It was his first time speaking in public and on such a momentous occasion, no less. He was there of his own volition, to fight for the first school he ever felt proud to belong to.

Ryan related the journey that had brought him to El Centro de Estudiantes. He talked about his experiences in the art class and his internship at a motorcycle shop. “Now I know for a fact that the alternative schools the school district runs do not have classes like this,” he said, reading from his notes. “I’ve had my experiences. I went to CEP and it wasn’t fun … It had packed classes filled with disruptive kids, no learning happening there, and I felt as though they were always violating my space by searching us whenever they wanted to. Even when I would go in the morning, they would make us walk through metal detectors, but that wasn’t enough, because they would still search us by hand.”

El Centro was different. “There are no metal detectors. We don’t get searched. It’s just way better. I can’t even call El Centro an alternative school. To me, an alternative school feels like a prison, but El Centro feels like home. Don’t take away my home.” He ended by thanking his teacher for helping him with the speech. “Our teachers from El Centro are still here up until seven, seven I don’t know, seven something, but they still here fighting with us to keep our school open. We don’t want our school closed.”

El Centro was different

For many of the students, it felt like no high school wanted them. El Centro de Estudiantes was the first institution to accept them unconditionally because of their blotchy academic and disciplinary records. Closing the school would mean forfeiting small class sizes, progressive teaching methods, and internships for the same old humdrum, violent schools they were pushed out of.

Bromley noticed that the fight was the “perfect medicine” to improve the school’s culture. Some of the kids who were making trouble at City Hall barely showed up to school. He was outside City Hall one day. When was the last time we had this many kids in our building? he thought. Ryan witnessed the massive enthusiasm and turnout and figured that the city had no choice but to listen and come up with a plan to keep the schools open.

He was right. A few days later, the City Council shot down [former Mayor Michael] Nutter’s soda tax proposal, but voted to increase property taxes and street meter parking rates. When supplemented with other funds, the measure would raise $53 million, a portion of which would help bail out the alternative schools. Direct action got the goods, and El Centro de Estudiantes was spared.

Ryan was relieved but wondered whether the anguish could have been avoided. Why did they have to beg the people in power for public schools that respected and helped their students? Why wasn’t that a basic right for all?

Excerpt from LIVE TO SEE THE DAY: Coming of Age in American Poverty, published by Metropolitan Books. Reprinted with permission. Copyright © 2023 by Nikhil Goyal.

![]() MORE ON EDUCATION FROM THE CITIZEN

MORE ON EDUCATION FROM THE CITIZEN