UCLA planning professor Michael Manville recently coined the term “pretextual planning” to refer to a phenomenon that Philly housing politics watchers will immediately recognize.

The idea is that city governments will sometimes intentionally put in place bad rules governing housing and land use and other issues, in order to use the removal of the bad rules as negotiating currency for some other agenda.

MORE ON PHILLY’S ZONING WOES

- Kenney zoning vs. Kenney planning?

- City Council bill ushers in a new politics of zoning

- Is there an end to parking neighborhood parking battles?

- Planning is the alternative to Councilmanic Prerogative

- What Philly could learn from Portland’s zoning reform

In other words, rather than planning for what we do want, and trying to write laws that will produce those outcomes, politicians will create or leave in place laws that everybody knows aren’t meant to be followed, and can be negotiated away at the politician’s discretion.

Once you recognize this dynamic, it’s impossible not to see it everywhere in city government, and especially in the housing and transportation issue area. It matters because it’s both an important source of political corruption—of both the legal and illegal variety—and one that is increasingly undermining the more planning-forward, rule-based approach to zoning reform that Mayors going back to John Street and Michael Nutter worked hard to build over the last 20 years.

You might think under the circumstances that local elected officials would show some interest in trying to do things to ensure there are enough places for people to live, but in reality, City Council has instead been working very hard to slow things down or stop new house-building altogether.

One of the things that the 2007-2012 Zoning Code Commission accomplished was clearing away the underbrush of a lot of haphazard zoning overlay districts that Council had put in over the years. But almost 10 years later, Council has managed to clutter it all up again with dozens of reactive little districts. Almost every area of the city has at least one overlay, according to this city map, and some places have several stacked on top of each other.

In a January article on this topic, I explained the overlay problem this way:

The main thing to know about zoning overlays is that they’re like a little patch of zoning on top of some other zoning. Every parcel of land in the city is assigned a zoning category, which specifies some rules about what can be built there.

These are the building blocks of the code, and City Councilmembers a lot of leverage over how to map them across their districts because of Councilmanic Prerogative. But City Council can also write some other rules to “overlay” on top of these base zoning rules, with the aim of achieving some specific policy ends.

Sometimes these are well-crafted and have a purpose that’s complementary to the goals of the city’s comprehensive plan, so the point isn’t that they’re all bad. But a lot of overlays run counter to the goals of the city’s Comprehensive Plan, for examples ones introduced by Council President Darrell Clarke, or 8th District Councilmember Cindy Bass that just add in extra parking requirements or other things that City Council as a whole has chosen to reduce or eliminate from the code in the recent past.

This is something Clarke and other dissenters have been trying to reinstate citywide, but they keep not having the votes to do it, so what they’re doing instead is abusing Councilmanic Prerogative to make side deals for specific areas.

The substance of these side deals is often misguided, but what’s even more concerning is the general trend toward more and more of these overlays piling up because this makes it much harder to pass truly citywide land use policy changes, and it even further undermines the crucial role of the Mayor and the Planning Commission in city land use, housing, and transportation policy.

Ever since Mark Squilla’s Society Hill Overlay passed—which Mayor Kenney vetoed with four Councilmembers voting to sustain—there’s been a torrent of zoning overlays from City Council’s District members, spreading like an invasive species through the city code.

The most egregious example by far is from 5th District Councilmember and Council President Darrell Clarke, which is about as perfect an example of “pretextual” planning as you’ll find anywhere.

Clarke’s bill (210486), which just passed the full Council unanimously last Thursday (thanks Councilmanic Prerogative!) creates a new 38-foot height limit for the massively-wide Girard Avenue for the entire area between N. Broad Street and 6th Street—a stretch comprised of mostly suburban-style strip malls where the city is currently pursuing federal funding to greatly upgrade trolley service on Girard (and in West Philly and Delaware County) to something more like light rail.

Mayor Kenney should stand by his Planning Commissioners’ recommendation and veto the bill, even if only to send a public message.

Nobody actually believes that Council President Clarke thinks it would look good if all the buildings along Girard were 38 feet tall. The goal is completely pretextual: It’s to force any building proposal of significant size to seek a zoning variance, which means a much more discretionary and political process where Clarke can personally have more influence.

The likely impetus for the bill are two building proposals now in motion closer to Broad and Girard that both would redevelop some of the strip-mall-style properties as dense apartment housing. Clarke—who once quipped approvingly that Philadelphians all drive to the corner store—is not a fan of this trend.

In the past, Council President Clarke has mainly used his discretionary influence to force a lot more parking into buildings, or reduce the amount of housing for all the typical reasons people push for that. Much of the area in question sits in yet another Clarke-originated overlay district, where the only thing different from the regular zoning code is that apartment buildings are required to have more parking—a dead-end policy for housing affordability, sustainable transportation, and the climate.

Not to mention that Philadelphia is right now facing a historic housing shortage and fast-rising prices as a result. You might think under the circumstances that local elected officials would show some interest in trying to do things to scale up housing construction and ensure there are enough places for people to live, but in reality, City Council has instead been working very hard to slow things down or stop new house-building altogether.

This Girard Ave downzoning alone could cost the city thousands of homes in the medium-term, right in an area that the Kenney administration is targeting for better transportation upgrades. It’s an unbelievably short-sighted and irresponsible move.

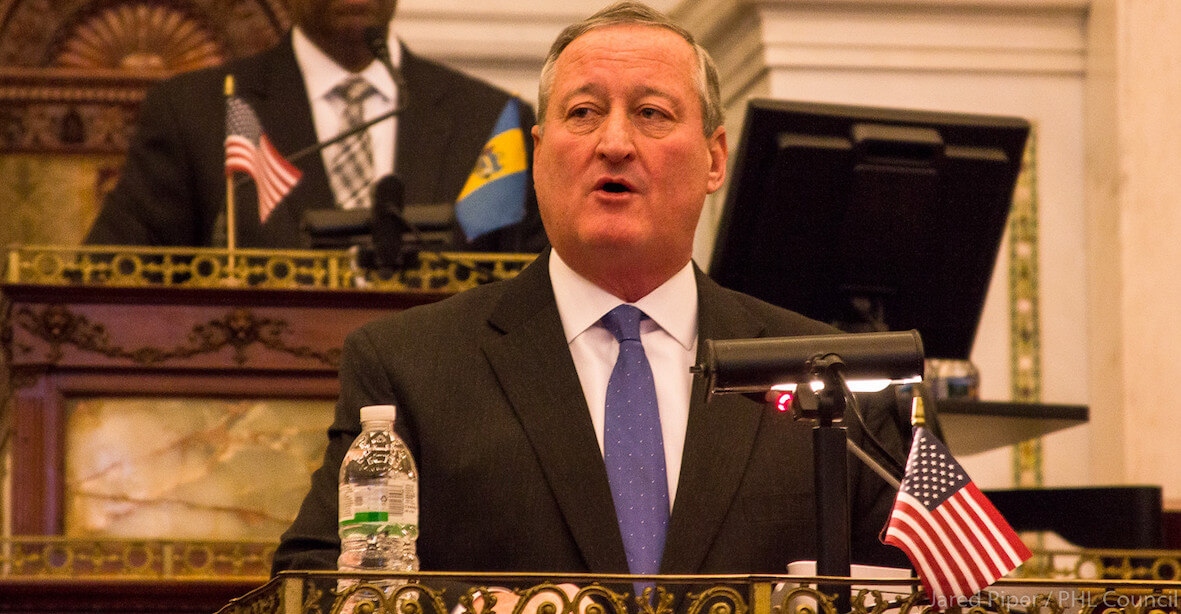

Mayor Kenney’s disinterest in fighting back against the progression of this agenda his entire term has been an unqualified disaster for Philadelphia’s planning institutions, and he’s going to leave office having forfeited a sizable amount of the Mayor’s power to City Council as an institution by the time his term ends.

Mayor Kenney’s Planning Commission did not recommend passage of the bill when it came before them, for the reason that most of it could have been achieved through the normal zoning mapping process, rather than an overlay, but also that the bill runs counter to city plans calling for more transit-accessible housing on major corridors like Girard, and near major subway stations like the one at Broad and Girard, or the new trolley station platforms that will eventually go in.

That last point is important, because Girard is home to the Route 15 trolley, which is slated for some big upgrades as part of the SEPTA trolley modernization program. Trolley modernization is the Kenney administration’s top infrastructure ask to the federal government right now, and the main project that Philadelphia specifically could get funding for as part of the transportation and infrastructure bills working their way through Congress.

In addition, the kinds of land use rules Clarke wants to pass are also exactly the kinds of rules President Biden and national Democrats increasingly want to see removed as a condition for receiving more federal funding in the future.

Federal funding is based in part on ridership projections and other economic impacts that now are jeopardized by Clarke’s overlay bill, which is plainly just a power grab with no rational basis.

Mayor Kenney should stand by his Planning Commissioners’ recommendation and veto the bill, even if only to send a public message. As happened with his veto of Mark Squilla’s Society Hill Overlay—the one that really opened the floodgates to this trend in the last year—it’s likely that City Council will have the votes to override it in the end. But the Mayor should cue up another high-profile vote like the Society Hill one to drive home some important messages that Council isn’t getting:

- That pretextual planning is bad planning, and lawmakers should try and legislate for what they actually want to see happen;

- That Overlay Mania is killing our planning institutions, and Council should go back to legislating through the regular processes for mapping and updating the code;

- And that Council should support any federal transit investments we might get by allowing more housing opportunities nearby—not closing off opportunities for more people to live near our best transit service.

This is all really a norm-breaking departure from what had been standard procedure up until recently, and the path-breakingness of what’s been happening mostly hasn’t been conveyed by our greatly-diminished housing media, with the exception of this January article by Ryan Briggs at WHYY. Since that piece was published, even more zoning overlays have passed City Council, like an invasive species sprawling across the code.

Mayor Kenney’s disinterest in fighting back against the progression of this agenda his entire term has been an unqualified disaster for Philadelphia’s planning institutions, and he’s going to leave office having forfeited a sizable amount of the Mayor’s power to City Council as an institution by the time his term ends.

The best Mayor Kenney can do at this point is use his veto pen a lot more often to sound the alarm about what’s happening, and help draw more critical media attention to City Council’s pattern of abusing Councilmanic Prerogative ahead of the 2023 elections.

Jon Geeting is the director of engagement at Philadelphia 3.0, a political action committee that supports efforts to reform and modernize City Hall. This is part of a series of articles running on both The Citizen and 3.0’s blog.

Header photo via Wikimedia Commons