Some might say Philadelphia feted its new City Council, re-elected mayor and other political luminaries in proper Broad Street-style at the Met on Monday. Some might say they could have done away with all the pomp and just carried out the ceremony at City Hall. But, one thing most seem to agree on is that while we might have a sense of the issues and priorities for 2020, we don’t have that much sense of exactly what the plan is.

![]() “That’s what we’re looking for,” said Black Women Leadership Council (BWLC)’s Emma Chappelle during a post-inauguration panel broadcast on WURD. “We’re looking for the plan. How does everyone in the leadership play a role in that plan? And, what exactly are they going to do to get it done?”

“That’s what we’re looking for,” said Black Women Leadership Council (BWLC)’s Emma Chappelle during a post-inauguration panel broadcast on WURD. “We’re looking for the plan. How does everyone in the leadership play a role in that plan? And, what exactly are they going to do to get it done?”

Trying to capture it all, City Council President Darrell Clarke spoke of a Philly “moonshot” moment as the “economy is booming and cranes are everywhere.” He lifted moon rhymes from the nation’s one-time race to the dead planet that everyone but the Boomers had forgotten about. “That’s an effort worthy of a world-class city.”

![]() That made insiders like BWLC founder Joann Bell bristle. “We’re a tale of two cities, and while the economy is booming, let’s be honest that it’s only working for some. The investments are from and they’re certainly not in people of color.”

That made insiders like BWLC founder Joann Bell bristle. “We’re a tale of two cities, and while the economy is booming, let’s be honest that it’s only working for some. The investments are from and they’re certainly not in people of color.”

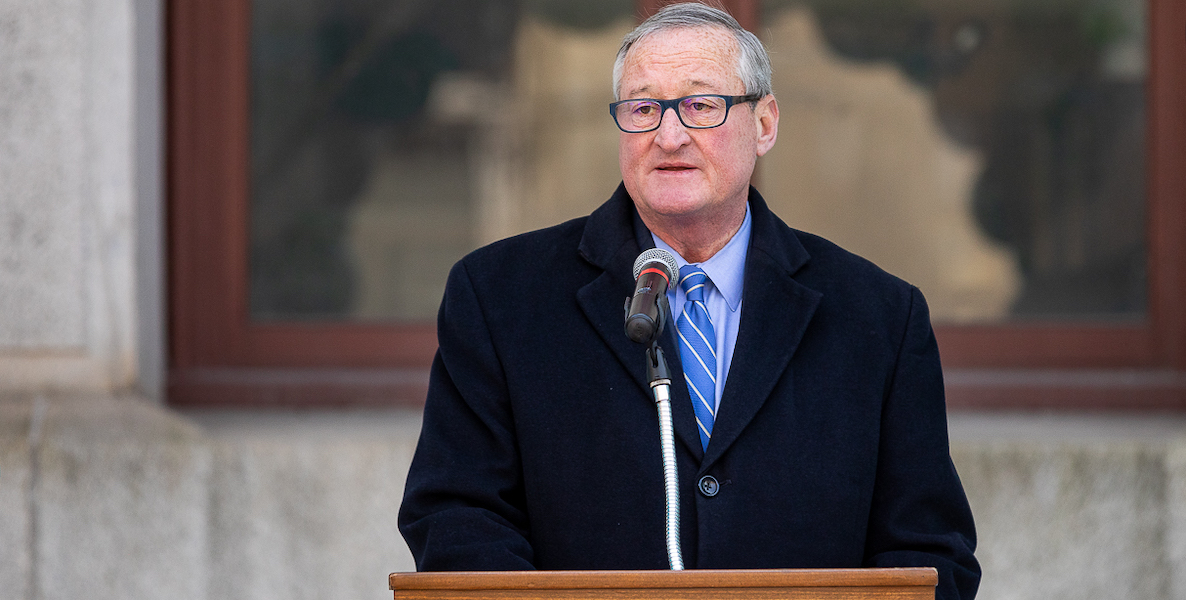

That list of concerns, of course, goes on and on. And as it piles up, unforeseen questions abound. What’s re-elected Mayor Jim Kenney’s mission in his second and last term? Is it just legacy, or is he aiming for Harrisburg, or Congress? What we do know is that he’ll need to do something better, stronger, more ambitious than what he’s been doing about Philly’s violence problem.

His blunt acknowledgement of the issue may score passion points, but it’s not like he’s rushing to the hospital or the scenes of grisly crimes when a resident gets shot the same way he did when six officers were shot down in Nicetown.

He’s definitely riding on the historic pick of Danielle Outlaw as Philly’s first Black woman police chief. But, Black Philadelphians have outgrown Black Philly firsts, either sucking teeth or blowing raspberries as they wonder out loud if Black Philly firsts are going to work for them and their household bottom line.

Activists got what they demanded: a Black woman police chief. But can she manage 6,500 officers after managing less than 900 in a city a quarter the size of Philly? And will she be an accessible “people’s commissioner” versus a police union commissioner?

The other question looming is how much the mayor is aligned with City Council, the old and the new? On that question, there is compounded uncertainty and gossip: The mayor pocket-vetoed six major Council priorities at the end of 2019—a first time for him—and forced what some viewed as a petty compromise on the phased tax abatement.

Arguably, it’s not a good way to kick off relations with a new Council in 2020. The mayor might have offered the obligatory thanking and congratulating of the Council in his inaugural speech, but he sure didn’t say anything about them as partners, something folks noticed.

Gilmore Richardson, the only one in that bunch to have actually worked as a Council staffer, may be the quiet X-factor and answer in all this: her career as City Hall institutionalist could position her as a shadow navigator or leader of that “squad.”

In contrast, City Council President Darrell Clarke did mention—once—“working collaboratively” with the mayor and giving Kenney “credit” for progress on community school expansion. But, notably, neither laid out any plans for what collaboration between the city’s main policymaking institutions could be in 2020.

“Both speeches were in two different places,” Rita Hill, also of the BWLC, observed on WURD. The mayor seemed a bit more multi-prong while the Council president more 10-year-business-plan. For Hill, though, “the collaboration theme was missing.”

Or, maybe, Kenney and Clarke are thinking that a new term and a new Council translates into a new slate. There are new members, three of whom enter the Council chamber with very limited—if any— knowledge of how the place works. That may present tactical opportunities to both. And it may not, depending on the temperature in the room and how those new members can finesse older sensibilities.

This comes with a cascade of unknowns. Conventional wisdom in Philly dwells hard on the new Council veering “further left.” But how much more left can you go in a City Hall as left as this? The real question is how intense will the generational clash be as opposed to the ideological differences: there are four new members—Kendra Brooks, Jamie Gauthier, Isaiah Thomas and Katherine Gilmore Richardson—including two millennials and two Gen-Xers.

Gilmore Richardson, the only one in that bunch to have actually worked as a Council staffer, may be the quiet X-factor and answer in all this: her career as City Hall institutionalist could position her as a shadow navigator or leader of that “squad.”

In the meantime, we may see the first signs of a generational clash over the city’s strategy on violence, with younger, more-progressive folks leaning toward tackling the issue from a systemic perspective—with fixes on poverty, jobs and better education—versus addressing the problem as a simple public-safety issue.

Much of the talk, for now, is around the one-woman party who’s “not here to make friends” Kendra Brooks, with the expectation that she’ll be Philly’s Black version of AOC. Her personal story inspires and blazes trails, along with the historic placement of an independent in the Council for the first time since 1980. But how independent could she be if she owes Councilwoman Helen Gym a huge political solid?

City Hall might be looking much younger and fresher in 2020. But that won’t make much of a difference if the city’s plan towards a better path is either non-existent or all chipped and tattered like the undone, unfinished floors in that Philly Met in need of more touch-up.

When her name was announced on Monday, her supporters in the audience were audibly the loudest. But the natural skeptics and observers wonder how that translates in the 2020 session—and how much mandate is that, really, when less than 30 percent of Philly voters turned out to vote last year?

“That is the big question: How exactly will these new Councilmembers be?” asked Mustafa Rashed of Bellevue Strategies during the Reality Check on WURD Strategist segment. “You still need nine of your colleagues to get something done, bills passed. There is still a process.”

That process in 2020 won’t be easy, particularly as there are clear contenders—like Gym and newly minted Majority Leader Cherrelle Parker—for mayor in 2023. When will we know they’re doing something to run for mayor … when will we know they’re not? And, with Philly being a golden key to unlock the Presidential electoral college prize that is Pennsylvania, the decisions made in City Hall could have ripple effects in terms of needed voter turnout for desperate Democrats.

Both mayor and City Council will have quite a bit to plan for. The top problems needing fixes already linger from 2019 into the new year and new decade: poverty, gun violence, schools, housing and taxes … perhaps, in that order of importance or, perhaps, shuffled around according to the mood and Philly sitrep that day.

![]() Other issues are the sleepers few either mention or public discussion won’t demand much on, such as the existential public-health threat of a damaged environment and worsening pollution. Transportation and the cost of SEPTA, along with crumbling infrastructure, is another. Homelessness might actually be on the rise in Philly, when you factor in the folks who won’t or can’t do shelters, and there is mounting uncertainty around how much Philly can rely on state and federal resources, anymore.

Other issues are the sleepers few either mention or public discussion won’t demand much on, such as the existential public-health threat of a damaged environment and worsening pollution. Transportation and the cost of SEPTA, along with crumbling infrastructure, is another. Homelessness might actually be on the rise in Philly, when you factor in the folks who won’t or can’t do shelters, and there is mounting uncertainty around how much Philly can rely on state and federal resources, anymore.

With the exception of Councilmembers Derek Green and Isaiah Thomas, few in City Hall are mentioning the 2020 Census—which could leave Black and Brown residents dangerously under-counted once again while the Commonwealth is projected to lose a Congressional seat. Just how alarmed city leaders are by single-digit percentage Black business ownership and economic development in a city that’s 43 percent Black doesn’t show in the way they act (or not) on it.

Here we are in another year and a potential fresh-start decade and still no pressure for Philly’s world-renowned academic, research and medical institutions to step up their role. We still don’t know the full extent of Philly’s very high adult-illiteracy rate—about a quarter of the adult population last checked. Don’t hold your nose waiting for term limits. And while criminal “justice” reform is always a good “progressive” talking point, reality sets in according to the ebb and flow of a scared electorate that can easily flip on that when the crime goes from bad to worse.

Ultimately, residents will need a plan for whatever comes their way. And they’ll wonder if city leaders are working together, even as they’ll demand more callouts and belligerence from the newcomers setting an expectation of protest. City Hall might be looking much younger and fresher in 2020, much like the neatly organized and makeshift collection of Councilmember podiums on the Met stage that chilly Monday morning of celebration. But that won’t make much of a difference if the city’s plan towards a better path is either non-existent or all chipped and tattered like the undone, unfinished floors in that same Philly Met in need of more touch-up.

Photo courtesy Jared Piper for Philadelphia City Council