to this story in CitizenCastListen

Shortly after a record high 3.3 million in weekly unemployment claims were announced, President Trump signed the CARES Act into law. The race to save our small businesses is on, and it promises to be a challenging one.

Over the past several weeks, many cities enacted local emergency relief funds to give small businesses the capital infusions they need to survive until larger pools of capital are made available through the federal government.

The federal government’s CARES Act created two relief vehicles: (a) a ~$350 billion Small Business Administration Paycheck Protection Program and (b) a Federal Reserve Main Street Business Lending Program.

Get the short version of this storyShort on Time?

In practice, it appears that the sequencing of relief packages will be anything but linear. Like the public health response, this will be messy and chaotic.

Many small businesses will collapse in the process. This is less a criticism of Congress and the agencies administering relief than a reflection on the complexity of the challenge before us.

Let us start by reviewing …

The three tiers of relief now in play

Local Emergency Funds

Local economies have not had the luxury of waiting for the passage and implementation of the CARES Act. Across the country, municipalities, philanthropies and related intermediaries have created emergency funding facilities for their small businesses, targeting a narrower definition of small businesses (generally 25 or fewer employees).

These facilities vary widely based on the needs and capabilities of any given place. This week, we detailed a typology of local funds that shows the disparate sources of capital, terms and conditions, and delivery systems organized into five main categories based on the entity leading the charge: city government funds, public entity funds, philanthropic funds, financial institution funds and business chamber funds.

From $100 million in Chicago’s Small Business Resiliency Loan Fund seeded by the City and administered by local Community Development Finance Institutions to the Indy Chamber’s proposed $10 million Rapid Response Loan Fund, community leaders are on the front lines trying to stop the bleeding.

Small Business Administration Paycheck Protection Program

Going forward, the Small Business Administration (SBA) will be a key scaled funding resource for businesses with under 500 employees: The CARES Act appropriated almost $350 billion to the new Paycheck Protection Program.

How YOU can help small businessesDo Something

The program appears to be well structured and accessible, but the quantity alone represents a massive distribution and execution challenge for many banks and the chronically underfunded and understaffed SBA (and may nonetheless prove to be insufficient in scale).

Federal Reserve Main Street Business Lending Program

The Federal Reserve is also wading into uncharted waters with its proposed Main Street Business Lending Program as part of the estimated ~$4 trillion of capacity created by the CARES Act.

The program is light on details to date, but the Fed is working to put it together. Some estimates predict an allocation of ~$1 trillion to this particular Main Street initiative, which will be focused on small businesses but also include midsize companies with up to 10,000 employees.

The Fed will look to bank intermediaries in order to distribute its loan program. It remains to be seen whether the program will truly reach small businesses in the most need, or be gobbled up by midsize corporations.

The presentation of this hierarchy of small business relief efforts is logical and ordered. But the real world of small businesses and the communities in which they are situated—atomistic, distributed, with intermediaries of widely varied capital and capacity—means that implementation of these packages will be more symbiotic and iterative than sequenced and separate.

The bad news is that the existence of CARES Act capital does not guarantee that it will serve its intended purpose. The good news is that the circumstances have forced action at the local level.

Three primary contentions regarding the period to come

The design and delivery of rescue capital will take longer than policymakers anticipate, meaning that capital will not reach many small businesses in time.

The SBA, and eventually the Fed, face an enormous challenge of scale, distribution, and delivery.

The SBA’s single largest FY2019 program represented $23 billion in loans. Moreover, during hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria, the SBA averaged a 70-day timeline to go from acceptance to initial disbursement.

The SBA has already had difficulty with its disaster loan application website in the face of Covid-19. Disbursing ~$350 billion represents an unprecedented challenge under any circumstance, not only for this agency but also for the many financial institutions tasked with deploying the capital. In these circumstances, with severely curtailed social interaction, timely distribution presents an even greater challenge.

The lending products offered and delivery system information will not touch many small businesses that operate on the periphery of our economy.

While the Paycheck Protection Program allows access for microbusinesses with ~10 or fewer employees (including sole proprietors), the systems in place are not set up to reach them.

This is a recurring problem we’ve seen with programs aimed to provide capital to places that need it the most: To be effective, these programs must establish local distribution capacity.

In particular, we worry about black-owned businesses which are already less likely to be approved for small business loans, compounding their already-stacked deck of less start-up capital and lower revenues than white-owned businesses.

If proper distribution systems are not set up, the nation risks losing tens of thousands of our most vulnerable businesses, hitting black-owned businesses and the neighborhoods they support especially hard.

The institutions tasked with delivering the federal response neither reflect the breadth of intermediaries with existing relationships with affected businesses, nor use technology platforms that can reach them in efficient and expeditious ways.

SBA certified lenders comprise a relatively small proportion of existing institutions. Distributing the volume of money that the SBA is tasked with will necessarily require a larger number of lenders.

The groups currently offering their help to reach the most vulnerable businesses include Community Development Finance Institutions (CDFI) and to lenders without SBA certification such as Financial Technology companies.

Fortunately, the SBA and Department of Treasury have authority to determine additional lenders.

The economic effects of the Covid-19 crisis have already been devastating, and like the virus itself, have the potential to rapidly multiply in the absence of well-targeted intervention.

So, what to do?

Despite the best intentions of policymakers, we believe that local efforts and intermediaries will play a larger role in providing relief to small businesses than previously understood.

This is not necessarily a bad thing, but it does mean these intermediaries must be properly empowered. This requires that the full financial system—layers of governments as well as multiple actors—take several intentional actions:

First, we need to support existing—and stand up new—local efforts to provide emergency funding to small businesses.

We are increasingly convinced that local funds will have to play an ongoing, indefinite, and expanded role in mitigating this crisis, and believe an initial $25 billion is needed for these funds immediately—compared to $500 million currently raised, by our conservative estimate.

We propose that already appropriated federal funds, to the greatest extent possible, be used to support local emergency funds to support small businesses and nonprofits, in addition to their efforts to reach businesses directly.

In the meantime, we encourage local governments, philanthropies, and private sector partners to continue supporting these funds.

We also need to erect a feedback loop between local and federal responses, so that local innovations can inform federal action that will iterate and evolve over time.

It is perpetually difficult for the federal government to understand the vast and varied needs of the smallest businesses in far-flung corners of the country. In this, local communities play a vital role in mobilizing to communicate the needs of their at-risk constituents upwards.

As President Roosevelt said in the depths of the Great Depression, “the country demands bold, persistent experimentation.” This crisis demands that successful local experimentation rapidly informs the ongoing federal responses.

We propose that the federal government expand the remit of the White House Opportunity and Revitalization Council to act as a channel between a subset of the local emergency funds that have been established and the federal agencies tasked to lead the economic rescue.

Many local economic development institutions are repurposing their focus in response to this crisis; so too can the federal government.

We, finally, need to get outside the box and engage a broader group of financial institutions, local and beyond.

Our assessment of local relief efforts shows the critical role being played by local, regional and national CDFIs, private financial institutions that are 100 percent dedicated to lending in ways that support broad-based community wealth.

Financial technology companies offer intriguing but largely untapped assets that have platforms to speed the delivery of resources to cash-strapped small businesses.

We propose that the SBA speed the eligibility process for banks, while the federal government explores ways—through the SBA, Fed, or otherwise—to engage local CDFI’s and financial technology companies as additional outlets and intermediaries to increase its reach and speed to market.

We also propose major financial institutions explore partnerships with CDFI’s to bridge the “distance” between large capital institutions and small businesses.

The economic effects of the Covid-19 crisis have already been devastating, and like the virus itself, have the potential to rapidly multiply in the absence of well-targeted intervention.

Help local restaurantsDO EVEN MORE

The good news is that the circumstances have forced action at the local level. If we can cooperate to support and understand the best practices being established on the ground, funnel that information into a feedback loop to inform other communities and the federal response, and engage a more holistic set of intermediaries to execute on these learnings, we may yet stand a chance to salvage our small businesses and establish a more effective financial system going forward.

Bruce Katz is the director of the Nowak Metro Finance Lab at Drexel University, created to help cities design new institutions and mechanisms that harness public, private and civic capital for transformative investment. Michael Saadine is a real estate and social impact investor. Colin Higgins is a program director at The Governance Project.

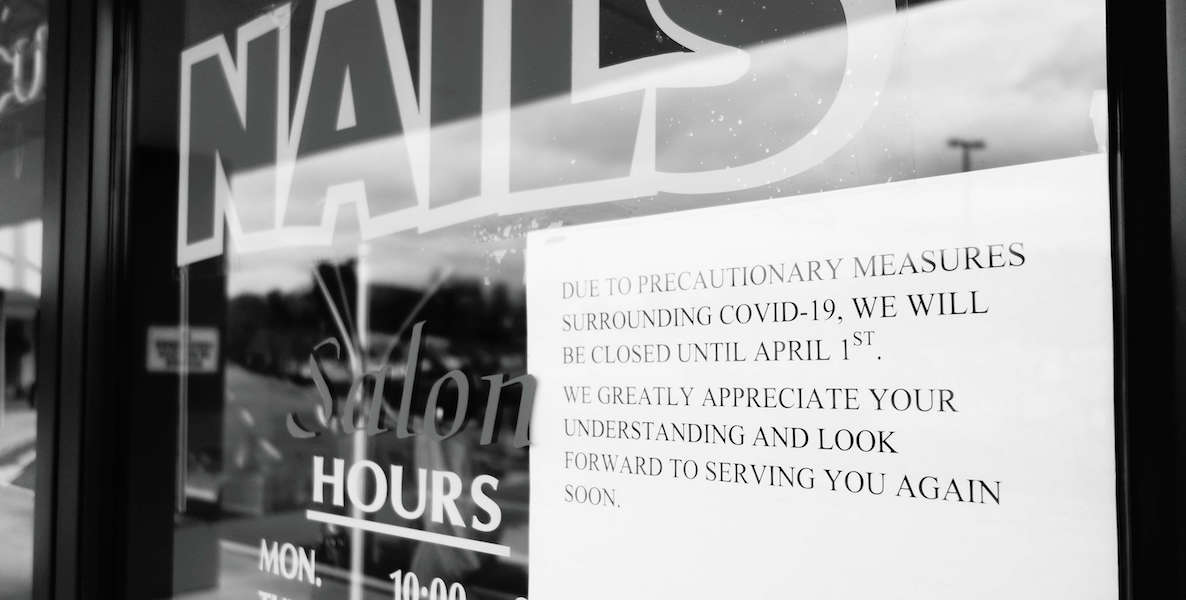

Photo courtesy Jon Taylor / Flickr