[Ed note: The Citizen is hosting its inaugural Ideas We Should Steal Festival on November 30th, at Drexel University’s Mandell Theater. Join us and Hear Cat Goughnour share more about community and what it could mean for Philly. See here for tickets and info.]

Let’s get the mea culpa out of the way first. In Anand Giridharadas’ 2015 TED talk, “A tale of two Americas. And the mini-mart where they collided,” he brilliantly calls me—and maybe you—out:

And don’t console yourself that you are the 99 percent. If you live near a Whole Foods, if no one in your family serves in the military, if you’re paid by the year, not the hour, if most people you know finished college, if no one you know uses meth, if you married once and remain married, if you’re not one of 65 million Americans with a criminal record—if any or all of these things describe you, then accept the possibility that actually, you may not know what’s going on and you may be part of the problem.

I first heard those words just after November, 2016—and the effect was visceral. All of Giridharadas’ conditions applied to me. I didn’t know any Trump voters—at least none that would cop to it. He made me realize: I had seen the problem, and it was me.

Electing Trump was a catastrophic mistake, but it wasn’t necessarily irrational. This idea that all of America between the coasts is some rural Alabaman racist paradise is a liberal delusion that just blows me away.

Well, now Giridharadas is back, with a book that is just as in-your-face, Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World. Along with ImpactPHL,The Economy League and B Lab, we’re bringing him here September 6 for a book signing and public discussion with Jay Coen Gilbert, the co-founder of the aforementioned B Lab, which has jumpstarted the international B Corp movement in an effort to prove that business can be a force for social good.

![]()

Giridharadas calls BS on much of the “conscious capitalism” movement in a way that ought to cause those of us championing it—the, I hate to admit it, elites—to look inward. “There is no denying that today’s elite may be among the more socially concerned elites in history,” he writes. “But it is also, by the cold logic of numbers, among the more predatory in history. By refusing to risk its way of life, by rejecting the idea that the powerful might have to sacrifice for the common good, it clings to a set of social arrangements that allow it to monopolize progress and then give symbolic scraps to the forsaken—many of whom wouldn’t need the scraps if the society were working right.”

You’ve probably seen Giridharadas, a former New York Times columnist, on MSNBC, where he’s a political analyst. He is that rare triple threat: Gifted writer, original thinker, dogged reporter. In Winners Take All, as he takes the reader on a travelogue through this strange land he calls “MarketWorld”—complete with its own language, with its “win-win” strategies and “thought leader” musings—you find yourself arguing with him while he challenges you to look at yourself.

There’s a problem when private giving buys decision-making authority in a democracy. When giving gives you a seat on a board, does it also give you veto power?

Full disclosure: I bring my own predilections to this all-important discussion. Our recently deceased Chairman Jeremy Nowak invented social impact before it was even a term, when, in the 1980s, he founded The Reinvestment Fund and turned a $10,000 grant into over a billion dollars of development in distressed inner-city neighborhoods. He built a financial institution that, in effect, raised money from corporations and wealthy individuals, leveraged it with public dollars, and lent it to developers who built affordable housing and grocery stores in food deserts.

So I’ve seen how the power of market-based solutions can make real differences in real people’s lives. Turning Giridharadas’ pages, I couldn’t stop asking myself: “What would Jeremy think?” And I think he’d actually appreciate much of Giridharadas’ critique, for Nowak was also blessed with a robust BS detector. And the world Giridharadas found himself in a couple of years ago, which was the genesis of his book, was ripe with BS, where lofty tales of changing the world often masked little more than clever marketing.

I caught up with Giridharadas, whose book was reviewed on the front of the New York Times Book Review last week, to talk in advance of his September 6 visit about these timely issues. The following is a condensed and edited version of our conversation.

LP: So you don’t spend a lot of time in the book on it, but in the summer of 2015, you gave a controversial speech at the Aspen Institute that first laid out your thesis. How did that come to be, and what was the fallout?

AG: In early 2011, I was made a Henry Crown Fellow at the Aspen Institute. It’s one of many such programs—like those at Davos or YPO—that aims to take youngish people from business or the entrepreneurial class and grow them into being social change agents. The way it works is, there are about 20 people in a class, and usually 2 or 3 are not business people, in order to spice it up a bit and include a slightly different perspective. The purpose is to get you to paint on a broader canvas, to move from “success to significance.” That’s when you start hearing about “changing the world.”

![]()

You meet four times over two years, and you read the classics, like Aristotle and Plato. In retrospect, I should have seen it as a sign of things to come that Jack Welch was also on the reading list. I should have picked up on that. [Laughs]

The whole purpose is to explore who you are. And as these conversations went on, I started to have doubts. The classes took place in the Koch Brothers Seminar Building and Goldman Sachs sponsored our lunch, which was an opportunity to advertise itself to us as a do-gooder company. So here we had these privileged business people coming together to “change the world”—sponsored by Monsanto.

I found myself in the rooms where it happens, among a global plutocracy superclass that makes important decisions that affect the rest of us. The good things they were doing started to seem inseparable from the larger system they upheld. Giving was the handmaiden of their taking. While claiming to change the world with talks of market-based “win-wins,” they were really rigging the world to their benefit. So I was asked to give a TED Talk-like speech there. In mid-2011, I had written a column for The Times headlined “Real Change Requires Politics,” in which I talk about this tendency for elites to define change down so that we forget what real change looks like. When Pope Francis in the summer of 2015 released a big statement that was critical of capitalism, I thought, Talk about a guy with a lot of pressure to not say stuff like this. If he can say this, why not little old me? So I decided to update my column for the Aspen speech.

Giridharadas calls BS on much of the “conscious capitalism” movement in a way that ought to cause those of us championing it—the, I hate to admit it, elites—to look inward.

LP: A critique from the belly of the beast, so to speak.

AG: The people in that room I knew to be decent. They were sincere, but enmeshed in a big mistake that was hard for them to see. You know, I’ve thought about this a lot lately. There has to be some point in keeping writers around. Society keeps us around for a reason—our job is to be the village crier when something’s not right. What was the point of me seeing all this—this cultural moment of using change to keep things the same—if not to call it out?

LP: You coin the phrase “MarketWorld.” What is it?

AG: It’s a complex of people and institutions that believe it’s possible to do well and do good. To change the world while also benefiting from the status quo. To make a difference while making a killing. MarketWorld includes foundations that give away money but don’t want to talk about how that money was made. MarketWorld talks about opportunity instead of inequality. It’s a state of mind—its values are neoliberal and technocratic and assume some of the historic aspirations of the left. But it seeks to achieve those goals within the framework of a market-centric world where private sector actions are all that’s available. It believes that government has been discredited for a reason and that markets can solve problems governments used to solve.

LP: But government has been discredited, right? Isn’t it the case that government can no longer solely address all of society’s ills? At The Citizen, we really focus on cities and what we’re seeing, in places like Pittsburgh, is leadership that comes from government working with business leaders and nonprofit foundations to serve the common good.

AG: There’s no question that government is dysfunctional in a bad way right now. Is there a role for the private sector to play? Yes. But the question is, how does it play that role?

I don’t know the specifics of Pittsburgh, but I’d ask if the help from foundations there is structured in a way that gives private actors important decision-making power at the expense of properly elected deliberative bodies? There’s a problem when private giving buys decision-making authority in a democracy. When giving gives you a seat on a board, does it also give you veto power?

LP: You actually break some news in Winners Take All, seems to me. Your critique of the Clinton Global Initiative is withering, and, in an interview, you actually get President Clinton to seemingly rethink his globalist ways.

AG: He basically said he wouldn’t have signed NAFTA if he knew then what he knows now. It’s difficult to see the bullshit of your age when you’re in it. There was just so much rich-‘splaining around trade. We were told that free trade would be good for GDP. Well, it was good right away for lobbyists and big companies. But it wasn’t good for Bob from Mahoning County, Ohio, who had no role in this strategy and who doesn’t live in economic aggregates. Bob is just Bob, and in 2016 he told us, ‘The new world you’re talking about isn’t working for me.’

LP: In that sense, though the thought is anathema if you’re inside our progressive bubble, maybe the vote for Trump in 2016 wasn’t so irrational.

![]()

AG: I’ve said exactly that. Electing Trump was a catastrophic mistake, but it wasn’t necessarily irrational. This idea that all of America between the coasts is some rural Alabaman racist paradise is a liberal delusion that just blows me away.

LP: The Clintons had 25 years to figure out how to move those who would be adversely affected by NAFTA to something better, and they didn’t. And then Hillary Clinton loses because white working class voters that had twice voted for Obama voted for the crass billionaire.

AG: That’s right. You can’t make this stuff up.

LP: Your critique of the excesses of capitalism is dead-on, but it is generating its own response, isn’t it, a strain of capitalism that seeks to do good, as well? B Corps, social impact bonds, impact investing—hell, even Laurence Fink of BlackRock has demanded social impact of the companies he invests in—isn’t all that a good thing? Even if only out of self-interested marketing concerns, isn’t it better to have companies that seek to do right by the environment and their employees than companies that pollute and pay exploitative wages?

AG: Each of these things are good on their own, absolutely. Is B Corp Patagonia better than Exxon Mobil? Yeah, definitely better. The issue is how you define change. Jay, Andrew [Kassoy] and Bart [Houlahan] of B Lab do great work, and they’re friends of mine, but is certifying companies the best use of your time, or is it better to use the power of law and government to go after those who are doing harm? You mentioned BlackRock. We all read about Laurence Fink’s challenge. But what about what are we not reading about BlackRock? I’m curious about whether the good they do buys immunity from what else they’re doing. Where are they on the issue of carried interest? What are they lobbying for in D.C.? Does their impact mask other flaws?

LP: Anand, I can’t thank you enough for this book. As you can tell, it’s forced me to interrogate myself.

AG: That’s a good thing and good to hear. It’s what writers are supposed to do.

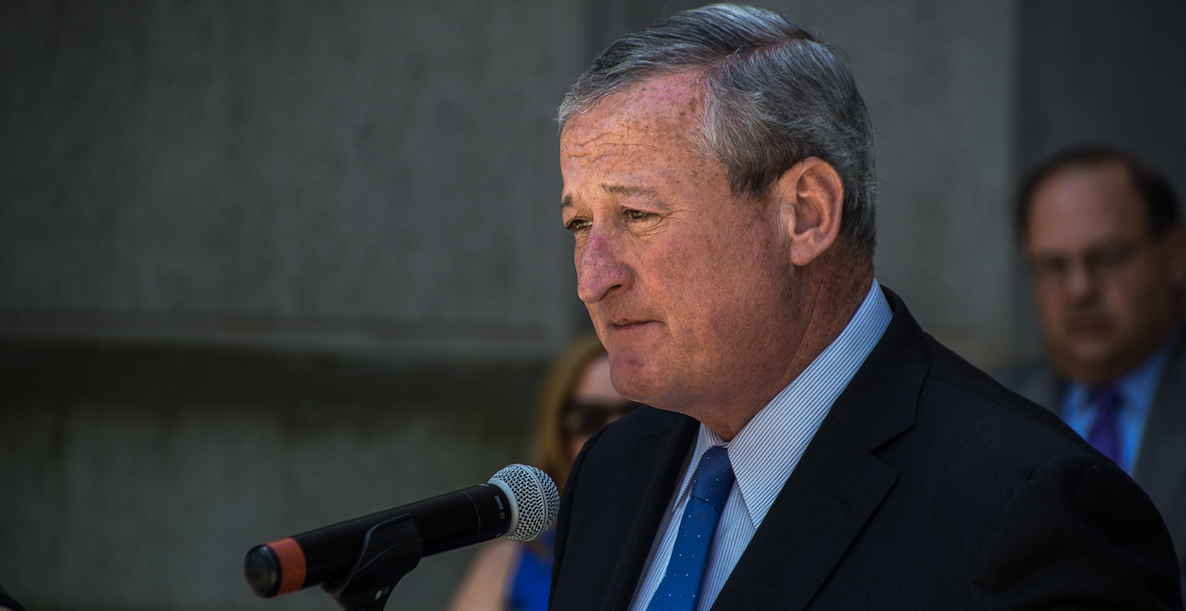

Photo by Kris Krüg for PopTech via Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0)