Another Democratic primary in Philadelphia, another year where voter turnout was pitifully below even the lowest standard set by the city officials who oversee our elections.

Races from local to state to federal were crowded and contentious this year, especially in Pennsylvania’s post-gerrymandered era. New Congressional districts offered new plot twists. Nowhere was the political drama more intense than in the Philly region, where House candidates pressed hard on the first step to Washington, D.C. and others similarly convinced themselves they had what it took to take on Harrisburg.

Others became acutely aware of the often unknown or less recognized Committee person seats which have gradually become a conversation piece. And even as Democratic primaries for Governor and U.S. Senate were uncontested, thereby paving the way for slightly easier paths for Gov. Tom Wolf (D-PA) and Senator Bob Casey (D-PA), this latest round of primaries certainly held enormous political value for everyone.

You would think that with the public obsessing so much over politics these days, people would be racing to their Philadelphia polling precinct that is, on average, only 6 or 7 blocks away. In Philly, where loud has always been fashion, anti-Trumpness—and the running tributaries of racial, social and economic injustice issues emanating from that stream—has precipitated a movement of collective indignation and policy finger-pointing. The polarized climate we find ourselves is a unifying force (as well as a solid alibi for public officials who can’t get anything done). The good thing is that it’s drawn much more attention to the political process and good old American protest.

The bad thing is that people still aren’t voting.

Instead, we not only got dreadfully low turnout—we got turnout that was lower than the already low turnout from last year’s highly anticipated District Attorney race. In Philadelphia, only 17 percent showed up at the polls–three percentage points below turnout in 2014, the last primary. Statewide, it was only 18 percent (out of nearly 9 million registered throughout the Commonwealth)—and, for all the end-of-the-world hyperventilating on the left, turnout was actually lower in Democratic primaries than in Republican primaries.

And as usual, turnout was either drastically low or non-existent in Philly’s most distressed and vulnerable neighborhoods. These are the areas that would need to vote the most given they’re the most directly affected by decisions made in the aftermath of elections.

A typical reflex is to bash the voters. Those of us plugged in are quick to point out the collective ignorance of residents who seem more apt to burn bandwidth on social media each day for something non-consequential than take an hour or two out of that same day for something that impacts their quality of life.

We do that when we see over 1 million residents in Philadelphia alone are classified as “registered voters.” Logic contends: If 63 percent of the city’s population is registered to vote then, naturally, 63 percent of the city’s population—if they were savvy enough to get registered in the first place—should know that an election is taking place. The same could be said for Pennsylvania’s nearly 9 million registered voters, about 70 percent of the Commonwealth’s population of 12.8 million.

But blame shouldn’t land on just voters alone. In the case of Philadelphia, public officials, city leaders, academic institutions and even media should also be shouldering that blame for allowing that disconnect to fester for so long.

If only 17 percent of the electorate is turning out, one should expect Philly’s government to run at only a 17 percent level of effectiveness.

We shouldn’t assume that every resident is a political junkie or savvy campaign operative who spends every waking moment following election build-ups and outcomes. We should, however, assume and demand that it is the job—the duty—of all city leaders, government employees and relevant agencies to create lasting vehicles for civic learning and to encourage full civic engagement.

Something’s got to give. And maybe now is the time for an urgent citywide brainstorm session on how, exactly, does Philly revive the voter mojo? Here are several ideas to start that conversation:

Changing the Election Mindset

Bad enough there is no urgency around low turnout elections. But as bad is how Philadelphia government is acting like full civic engagement, including full registered voter participation, is not essential to its survival. Yet, it is. No democratic institution can function or last without both input and full participation from constituents. That argument is even stronger for local or municipal-based elections where, as University of California San Diego’s Zoltan Hajnal finds, “turnout does affect policy outcomes.”

For all the end-of-the-world hyperventilating on the left, turnout was actually lower in Democratic primaries than in Republican primaries.

If only 17 percent of the electorate is turning out, one should expect Philly’s government to run at only a 17 percent level of effectiveness. City leaders, at the moment, are responding vigorously to just that 17 percent of the electorate. Philadelphians may not be seeing the kind of government they want or demand since only 17 percent of the population is directly participating in the first level of public policy activity.

Elected officials may be fine with a limited status quo. Still, the error in that thinking is that, long term, the city faces untold costs and devastation due to negligence, incompetence and city-wide instability brought on as a direct result of low voter participation.

Tying Budget to Performance

One radical idea to jumpstart the new mindset: Tying Philadelphia City Commissioner salaries to citywide voter turnout. If turnout can’t meet a certain majority voter benchmark (like 60 percent, or the proportion of registered voters to city residents, let’s say) or when voter turnout drops, City Council should penalize the people whose job it is to run our elections. This may not be such a bad idea for the Pennsylvania Department of State, either.

The goal is to secure and enforce a performance metric for the Commissioner’s office. To date, it has mainly been focused on simply registering voters, ensuring existing precincts are open and function, and counting the votes. Yet, what good is it organizing the party if no one shows up?

Turnout for the voteDo Something

Even better would be closing the City Commissioners office altogether, as lawsuits and petitions in recent years have called for. In the meantime, it’s time to set a better standard at the Commissioner’s office by demanding better performance.

Online Voting: After All, It is the 21st Century

Why not online voting? The benefits of online voting are legion: No longer do registered voters have an excuse for staying away from polling precincts, particularly those with a good excuse such as that boss who says you’ll get fired or have your pay docked because you came in late or left early. Plus, if done right, it makes the franchise easily accessible, thereby exponentially increasing turnout.

It remains astonishing that our society, the oldest functional democracy, makes voting polls on social media or voting by text for the next American Idol much easier than voting for life-and-death decisions such as who runs a city, state or nation.

Even better would be closing the City Commissioners office altogether, as lawsuits and petitions in recent years have called for. In the meantime, it’s time to set a better standard at the Commissioner’s office by demanding better performance.

Yet, we find ourselves stuck in anti-innovation-itis, a common affliction found amongst the intellectually lazy and permanently uncreative. We have collectively duped ourselves into thinking that online voting is a non-starter due to cybersecurity concerns; and yet, we fully trust online systems and various apps to handle our money. And when Facebook, literally, broke down, we’ve rushed into a frenzy of account deactivations, Congressional hearings and shaming Mark Zuckerberg to guarantee we get a better Facebook.

We outright dismiss online voting as a pariah, especially after local government in the District of Columbia tried it. Yet, the small nation of Estonia is able to do it, completely and successfully since 2005 because it made the types of investments needed to make it work.

As cybersecurity expert Mike Summers notes: “Why does the Estonian system work so well? One key reason stems from the government’s decision to begin issuing in 2002 electronic identification cards, which are credit-card-size ID cards embedded with a chip and protected by multiple pass codes. More recently, it has also started to hand out SIM-based mobile IDs linked to citizens’ smartphones. These electronic and mobile IDs are currently carried by 1.2 million Estonians (or 94 percent of the country’s population) and help Estonians file their tax returns and apply for jobs.”

Wouldn’t it be an appropriate and groundbreaking exercise if Philadelphia, the birthplace of democracy, was to pilot a citywide online voting system for elections? This would not only ensure much higher turnout from the ease and accessibility of system use, but it would put Philly on the map as an innovator in the field. Some of the largest and most prominent technological research institutions are based in Philadelphia. Why hasn’t this happened yet?

Lowering the Voting Age

Ok, we get it: Online voting is too science fiction for you? Got it. Although cell phones, drones and on-demand shopping to your door wasn’t too much science fiction just 40 years ago?

So, what about something much closer to home like lowering the voting age in Philadelphia to 16? This is also another rather surprisingly controversial topic and hard to discuss. On WURD’s Reality Check, where we raised the idea, we received just as many calls against it as we did for it. Several callers angrily dismissed it: “Why would I trust young people who are barely mature to make decisions about government?”

Stories from Charles D. EllisonRead More

Philadelphia could be a big city leader in lowering the voting age to 16; we don’t know the exact numbers of 16 and 17 year old residents in the city, but we do know they are a significant fraction of the nearly 111,000 15-19 year old residents in the most recent Census. We also know of evidence showing how turnout has dramatically increased in small cities that have approved voting at 16 and 17: in Takoma Park, MD and Hyattsville, MD, overall turnout in municipal elections increased substantially by 30 percent to 40 percent. Indeed, there is evidence showing adults are motivated to vote when they see their kids vote.

There has been quite a bit of excitement around young people organizing mass nationwide movements on gun violence, and yet society is unwilling to provide them with the tools to enact real policy change. By the time 15, 16 or 17 year old activists get to 18, most have lost the momentum and desire to get civically engaged, with many either not registering or electing not to vote altogether.

That’s tragic: as tragic as the abject failure of our school system—which the Mayor has now taken on—to mandate full, interactive curriculum on civics that motivates young people to not only vote, but to completely immerse themselves in better governance.

We’re not sure where Philly thinks it will go with continued low voter turnout. But we can already see that, based on the condition of many communities and the permanence of poverty, it’s definitely not where it could be.

Charles D. Ellison is Executive Producer and Host of “Reality Check,” which airs Monday-Thursday, 4-7 p.m. on WURD Radio (96.1FM/900AM). Check out The Citizen’s weekly segment on his show every Tuesday at 6 p.m. Ellison is also Principal of B|E Strategy, the Washington Correspondent for The Philadelphia Tribune and Contributing Politics Editor to TheRoot.com. Catch him if you can @ellisonreport on Twitter.

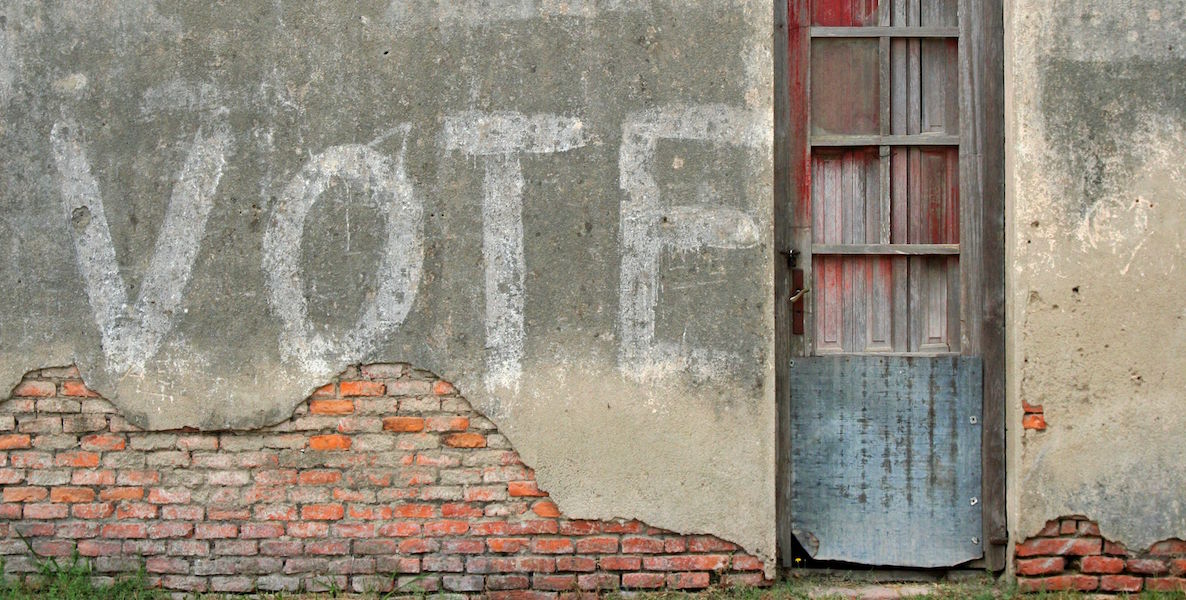

Photo: John Schneider via Flickr