As we look back at one of the worst weeks in U.S. history, with an unprecedented assault on our democratic institutions and processes, cities need to keep an eye on what’s ahead. In the chaos and tragedy of the week it was easy to lose sight of the message coming out of Tuesday’s Senate races in Georgia: Cities get ready, there is a multi-trillion-dollar stimulus coming.

Here's the quick readShort on Time?

There will be two, if not more, phases to federal action. The first phase will likely include another round of Covid-related relief; later, we anticipate a larger volume of recovery spending in infrastructure, innovation and workforce/human capital.

Friday’s jobs numbers show how desperately this money is needed: The economy lost 140,000 jobs in December, dashing hopes of a “V-shaped” recovery. The pandemic has rapidly increased its spread and the vaccine rollout is hitting logistical challenges. Relief and recovery resources are needed urgently. And the complicated operations of quickly and fairly distributing federal investments will be central to the speed of recovery in 2021—which has potential to be a quick bounce-back under the right circumstances.

Federal investments only work when they are designed, deployed and delivered by local entities who know their places best.

As we wrote in November and December: focused city, regional, county, and state networks will be essential for distributing this federal relief and recovery funding. It is imperative that local coalitions organize to navigate the dizzying array of funding sources—loan products, tax incentives, competitive grants, block grants—and agencies. If organized, city leaders can direct resources to local transformative and job-creating priorities, allowing them to make the greatest use of this federal investment.

If we have learned anything from 2020, it’s that federal investments work best when they are locally organized and amplified. Over the past year, city, metropolitan and regional leaders have played critical roles in responding to crises as they unfolded, deploying federal emergency resources and preparing for larger nationally driven recovery efforts. We expect 2021 to only build on this truism: Federal investments only work when they are designed, deployed and delivered by local entities who know their places best.

To that end, we recommend that, as soon as practicable, local leadership across sectors establish 18-month economic recovery centers to plan for, prioritize, and coordinate federal relief and recovery investments.

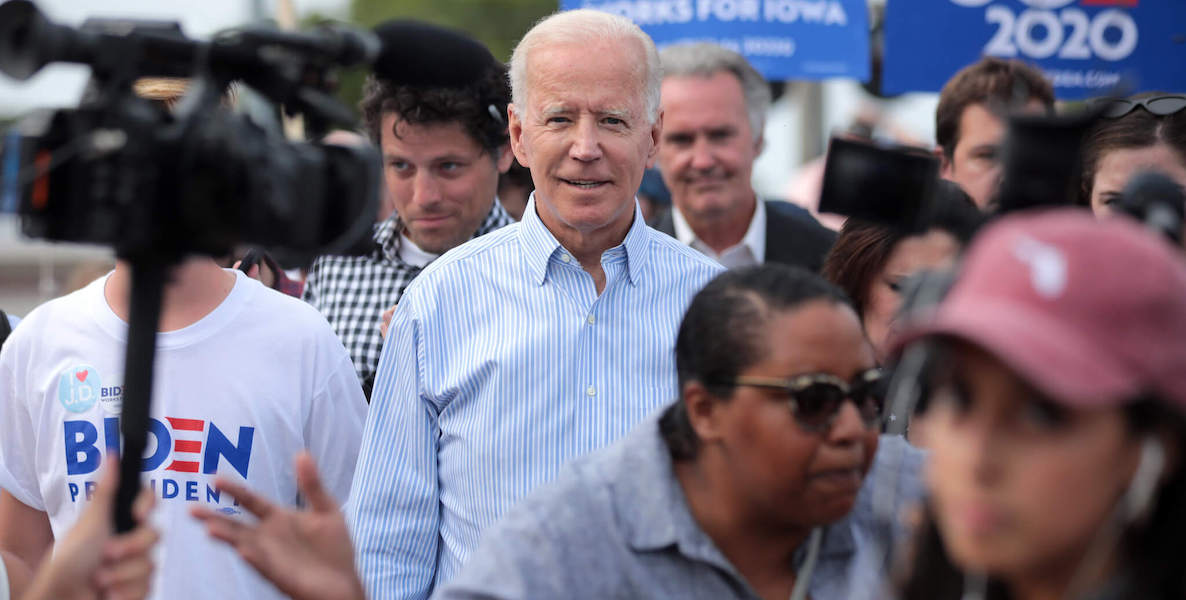

What to Expect in the Biden Stimulus

Democratic control of the House and Senate, alongside the president-elect’s recent statements, means that there will likely be relief and recovery packages in the trillions of dollars. It’s likely that the packages will occur in two parts: The first will include some form of immediate unemployment and small business aid, $1,400 checks, and relief for state and local governments. The second federal package, later in 2021, will probably contain three key buckets of countercyclical investments: infrastructure, human capital, and innovation.

This sequencing is important for local leaders across sectors. It means two things: (1) they will receive a first round of immediate relief to use for immediate budget shortfalls and urgent needs; and (2) they will have a bit more time to locally organize for maximum use of federal investments. Philanthropies take note: you should invest now to build capacity for planning!

As we wrote in December, these federal investments are likely to occur in vertical silos. This approach does not naturally align with the horizontal approaches to local economic development. If properly organized, the intersection between vertical federal approaches and horizontal local approaches can be harnessed to unlock a perpendicular approach to the national recovery.

Given the backgrounds of the key decision-makers involved, it’s likely that the countercyclical investment will follow similar outlines to the 2009 recovery, albeit with slightly different goals. This means it will utilize a mix of mandates, incentives and investments (e.g., tax incentives, financial products, block grants, competitive programs) coming from a myriad of federal agencies.

These federal investments, sometimes coordinated, oftentimes disjointed, will have maximum effect when they are braided and blended together with actions at the local and metropolitan level; in other words, when the vertical and the horizontal work together towards common goals. To maximize the impact of federal dollars, and to direct them to local priorities, local leaders need to prepare for the following categories of spending:

Infrastructure: Infrastructure spending is among the most important ways to drive a transformative recovery and put people back to work. President-elect Biden has made infrastructure a focal point of his Build Back Better agenda, with a $2 trillion package. The Moving America Forward Act, which House Democrats passed in summer, is illustrative of the breadth and magnitude of the coming infrastructure spend.

This $1.5 trillion bill also provides hints of what might be in an eventual infrastructure stimulus package: everything from typical infrastructure (transportation, water, aviation, rail) to significant spending on housing, broadband, and climate.

Key Agencies to watch: Secretary-nominee of Transportation, Pete Buttigieg, is a former mayor and understands how local economic development is organized. Therefore, the DOT will be an important “hotspot” for federal-to-local policy organizing on climate and infrastructure. HUD secretary-nominee Marcia Fudge’s experience as a mayor, along with the department’s block grants, means that HUD will be a central focus of federal-to-local innovation on housing and community redevelopment.

Human Capital: Alongside infrastructure investments, human capital investments are a vital component for bridging from a short- to mid- term recovery by retraining individuals and getting them back to work. President-elect Biden has proposed $50 billion in high quality workforce training programs. Models are also emerging in the Democrat controlled House; the Relaunching America’s Workforce Act, for example, provides $2 billion to fund the Trade Adjustment Assistance Community College and Career Training (TAACCCT) competitive grant program, used successfully during the Great Recession.

Key Agencies to Watch: Secretary-nominee of Labor, Marty Walsh, is also a mayor and former leader of the building trades union who has helped lead Boston’s workforce transition from traditional manufacturing to services. Meanwhile Secretary-nominee of Education Miguel Cardona has served in state and local executive roles as principal of a public school and education commissioner of Connecticut. This means both Departments will be vital “hot spots” to watch for federal-to-local interaction.

Innovation Districts and Inclusive GrowthAttend

Key Agency to Watch: Secretary-nominee of Commerce Gina Raimondo (Governor of Rhode Island) and Deputy Secretary-nominee of Commerce Don Graves both have decades of experience working across sectors at the local level to drive inclusive innovation, meaning the department will be another “hot spot” to watch.

How Cities Can Organize Their Priorities: Five Steps Local Leaders Should Follow

The federal government’s silos separated by language, culture and specialized expertise contrast with cities’ ability to nimbly match complex challenges with interdisciplinary, multi-sectoral solutions that are customized to local priorities, rather than compartmentalized, one-size-fits-all responses.

When operating in concert, these approaches can unlock the potential for a more comprehensive national recovery. This is why we are cautiously optimistic about the potential of the agencies we’ve flagged within the federal spend categories: they have leaders at the helm who have first-hand experience with local economic development and who understand horizontal approaches to problem-solving.

Local stakeholders would be wise to view the coming relief and recovery packages as the most important public investment in metro economies in this decade.

What’s important now is for local leaders to get organized to unlock the potential of this unprecedented moment. At stake is nothing less than the strength and inclusivity of local economies for the next decade or more.

Local stakeholders would be wise to view the coming relief and recovery packages as the most important public investment in metro economies in this decade. They should take the lessons of the previous three years to organize themselves around a plan to maximize the impact of the Covid-19 relief and recovery spending. In November we outlined a clear set of steps they should follow.

There are a growing number of metros across the country that are preparing and getting organized for federal investment along the lines that we outline below. Achieving the potential of a country as vast and varied as America requires allowing distinct metro regions to set priorities in line with their local strengths and assets.

First movers who have done this include: St. Louis, where a group of business and civic leaders have merged 5 separate business organizations and led the development of a draft 10 year economic plan focused on inclusive growth STL 2030 Jobs Plan | GreaterSTLInc; the Cleveland Innovation Project, which is a cross-sector, multidisciplinary alliance that can adequately represent the region’s capabilities and goals; and Philadelphia, where there is an emerging alliance of civic and business leaders focused on bolstering the city’s small business ecosystem and aligning local stakeholders for federal investment priorities, including building on The Enterprise Center’s pioneering efforts with their PPP Prep program. Other first movers are springing up around the country, including in Kansas City, Cincinnati, and other metros.

We recommend that local leaders work now to establish an 18-month economic recovery center to plan for and coordinate federal relief and recovery investments.

This center should be an executive-level task force, made up of leaders from the public, private, and civic sectors, that establishes a clear set of plans and priorities and maximizes the speed and effectiveness of the post-COVID recovery.

This economic recovery center should accomplish the following tasks by March:

- Outline concrete and implementable metro plans and priorities. The recovery center should know and position metro priorities around a key recovery narrative and actions in a short memo that will act as the ultimate guidance for local plans developed and federal asks that are made. These priorities need to be concrete, detailed and implementable. They should build on hard evidence about distinctive competitive assets and advantages. Doing so will pay dividends in applications for competitive grants, as well as block grant allocations, during the coming countercyclical investments in infrastructure, innovation, and human capital. Such an outline will also help clarify the public, private, and philanthropic funding for the project—leveraging up federal investments and helping drive the formation of local ecosystems across key local anchors.

- Align local priorities with the form and timing of federal investments. Once priorities are outlined, recovery center leadership should pay close attention to developments in Washington. As news comes out about the sequencing, funding products, and agency distribution of the stimulus, the Recovery Center should work quickly to position local priorities within the federal spending categories. If a local priority is not present, they should press their congressional delegations to expand eligibility.

- Ensure fair and effective fund deployment. The recovery center should coordinate and maximize local use of federal relief and recovery dollars. In the past, one of the biggest issues for metro economies trying to use relief and recovery bills is that countercyclical funds have been obligated but not deployed. The recovery center should set goals and coordinate local actors, institutions, and priorities in order to help deploy these funds more effectively. In this way, the recovery center can be a “clearinghouse” to understand what federal funds can be used for local projects and can ensure equity across neighborhoods in the process.

- Recruit recovery fellows to add capacity. Recovery center leadership should establish a corps of 3 to 5 executive-level local recovery fellows to enhance the capacity of local institutions to design, finance and deliver transformative revitalization. Modeled off of FUSE Corps fellowships, these fellows represent a key opportunity to recruit talent and deploy it locally to intensely focus on recovery. They are also a key area for philanthropy to impactfully deploy resources.

- Braid public, private and civic investments. Recovery centers should make every effort to leverage federal public money with private capital. This will not happen by itself. It will take dedicated work to coordinate efforts, engage the community, and attract capital. As was true for economic development initiatives of the last few years, local institutions and intermediaries — public authorities, CDFIs, urban land banks — will be essential to getting the job done here.

The Opportunity Ahead: Building Inclusive Economies for the Next Decade and Beyond

Building back better, in short, requires doing things differently. And not just for localities. For their part, federal leadership should design flexibility and true decision-making partnership into stimulus funds. Namely, secretary designees Buttigieg, Fudge, Walsh, Cardona, and Raimondo have experience as state and local executives and understand how local ecosystems work. They will be integral in designing flexible funds and programs that can unlock a perpendicular nation. In December we outlined five key ways that the federal government can do just this.

The Virus in the City seriesRead More

As such, it is imperative that they mobilize now to deploy the varied stimulus dollars efficiently and effectively. The infrastructure they build in the next few months will not only serve them to recover from our current crisis, but could permanently shape their economic development capability and growth trajectory for the next decade and beyond.

Attend the Innovation Districts and Inclusive Growth event, Wednesday, January 13 (today!), 11am EST, RSVP here.

Bruce Katz is the founding director of the Nowak Metro Finance Lab at Drexel University. Colin Higgins is a senior research fellow at the Nowak Metro Finance Lab. Andrew Petrisin is an associate consultant at WSP. Michael Saadine is a real estate and social impact investor.

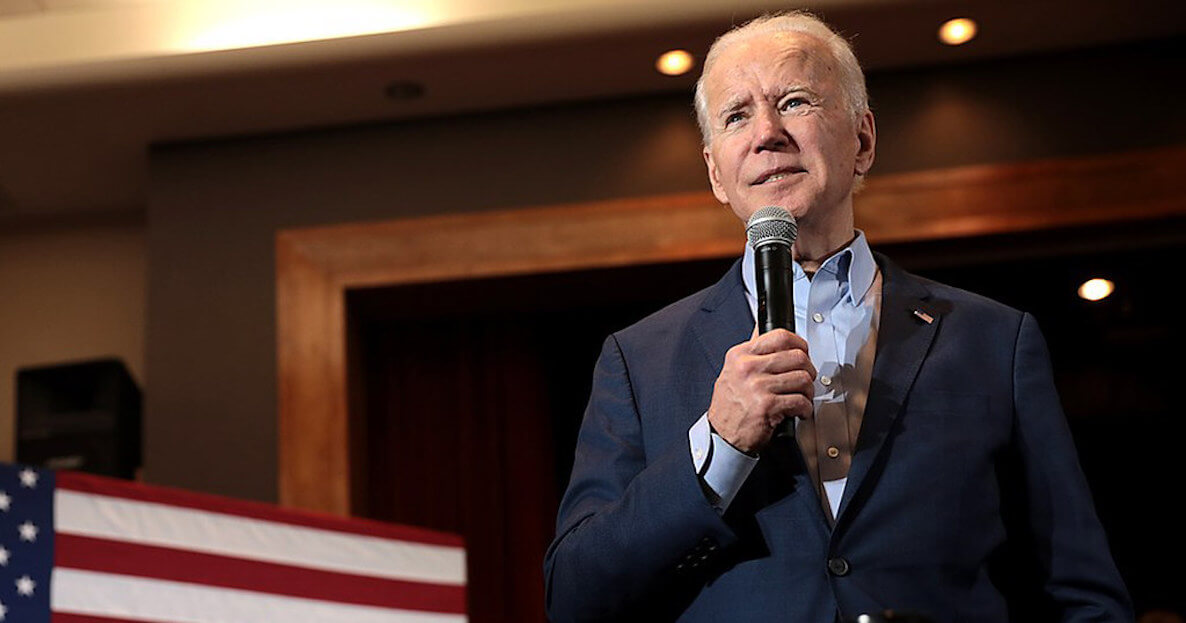

Photo by jlhervàs / Flickr