In an election season that will be remembered as proof positive that America has jumped the shark, it’s easy to despair about the state of our politics. In Philadelphia last year we had a Seinfeldian mayoral election, a campaign that was about nothing. Nary a mention of the $6 billion pension hole, anemic job growth or the worst poverty in the nation. And nationally? Well, Trump…combined with a Clinton campaign that is too calculating and scared to float fresh ideas (more on that later), resulting in a discourse of reflexive finger-pointing and ideological shibboleths, with hardly any exploration of common sense policy solutions.

Where are the creative ideas for a new day? We seem to get the same old tired debates—nationally, it’s about stimulus versus austerity—and locally, we debate which taxes to raise in order to implement new programs without even being told what the return on our investment might be.

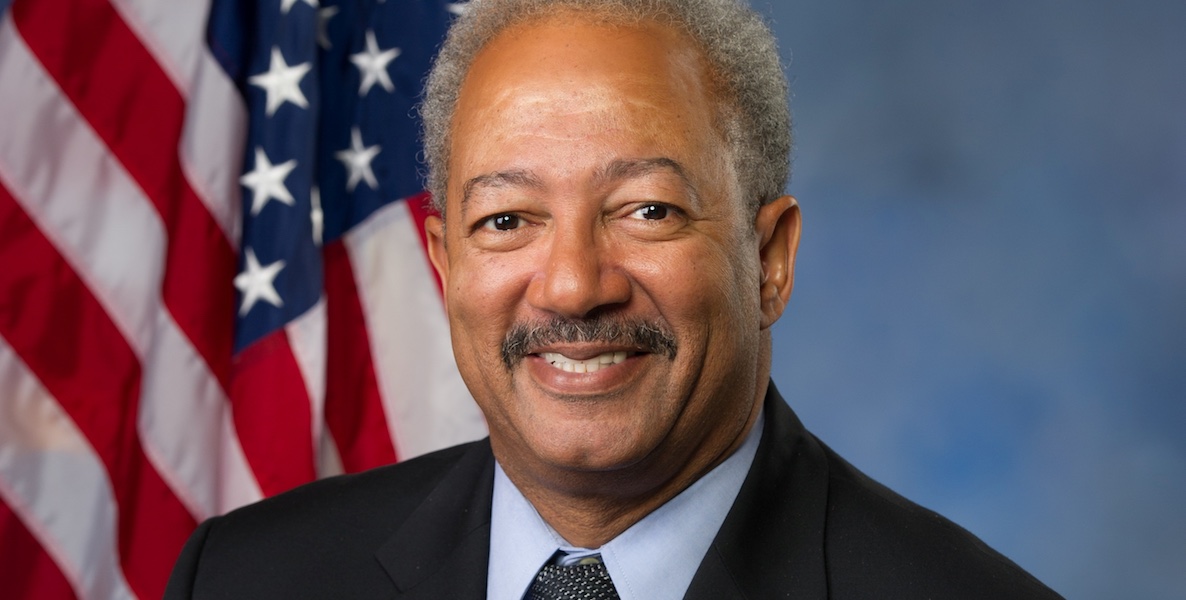

Into this depressing milieu has stepped one local candidate for public office, a throwback to the halcyon days when politicians researched best practices and sought to find new solutions to pressing problems. Joe Torsella, a former Rendell administration deputy mayor, founding President and CEO of The Constitution Center and, most recently, United Nations Ambassador, is running for state treasurer and making the case that the office doesn’t need to be either the province of a pocket-protector wearing numbers cruncher or a corrupt elected official. (The last elected Pennsylvania state treasurer’s tenure ended in a virtual perp walk; in the late ‘80s, Treasurer Budd Dwyer, caught red-handed, put a gun in his mouth and committed suicide during a live TV press conference.)

On election day 2014, Torsella learned that, across the country, state treasurer offices were being reimagined. A New York Times story detailed the ways many were tackling problems the federal government had no political will to confront, incendiary issues like income inequality. He read about San Francisco Treasurer Jose Cisneros’ program providing poor people with free or low-cost bank accounts after the treasurer had waged a successful campaign to get more low income residents to apply for the Earned Income Tax Credit, only to learn that half who applied had nowhere reputable to cash their checks. Then there was the financial literacy curriculum introduced into the Chicago schools by Illinois Treasurer Stephanie Neely.

“We’re one of four states to call ourselves a Commonwealth,” he says. “That word means something to me. The words I always come back to in thinking about my politics are words like Commonwealth and, especially, We The People. We haven’t always lived up to those words, but they speak to our best self.”

But Torsella, a one-time Rhodes Scholar and self-professed policy nerd, felt his pulse quicken when he read of a program started in Nevada by State Treasurer Kate Marshall, that seeds and provides a College Savings Account for every child in the state. Since the debut of Nevada’s program, other states have followed suit, including Rhode Island and Maine. After reading of Nevada’s innovation, Torsella called Marshall, whom he described as the “Madame Curie of this movement” when I caught up with him last week in the conference room of a Philly law firm, where he spends hours each day dialing for dollars. He seemed to welcome the chance to talk about the policy idea that, he says, gets him out of bed in the morning, and makes the act of telephonically trying to separate people from their money worthwhile.

“The Nevada idea popped for me because it was so simple,” he says. “We’re going to enroll every kid with a college savings account, seed it with a deposit from a partner, make it universal and automatic. The number is quite modest. There are 150,000 children born in Pennsylvania every year, so if we seed this program with $100 per child, that’s $15 million. The research shows that children with a college savings account are anywhere from 4 to 7 times more likely to attend college. It’s about saying to kids, ‘Our expectations for you are high and yours should be, too—you are a college-bound kid.’”

Torsella’s Keystone Savings Accounts would be codified as a 529 savings account, a tax-advantaged plan designed to encourage saving for college. But only 4.5 percent of eligible Pennsylvanians avail themselves of 529s, and they tend to be affluent. It’s the universality and seed money of the Keystone plan that makes it a weapon in the fight to shrink the income gap. And, as in Nevada and Rhode Island, it requires no outlay of public dollars. Funding would come either from a philanthropic partner or, as Torsella puts it, “entrepreneurially,” which aligns with the playbook in Nevada, where the program’s private sector money manager—in exchange for the business—seeds the $50 in each account. It’s a proposal that empowers people in a particularly economically divided time; in that sense, Torsella sees it not as a giveaway but an investment in economic development.

“This is a common sense, centrist idea that both parties should agree on,” he says. “It’s about raising expectations and results, and it’s about the economy of Pennsylvania. By 2020, 60 percent of all jobs in the state will require an associate degree or higher, and currently only 40 percent have that, and only 22 percent have bachelor degrees. If we raise the college attainment rate, we grow the economy and the tax base.”

A little over a decade ago, Great Britain passed Tony Blair’s vision for Baby Bonds, in which the government gives every newborn baby between 250 and 500 pounds, depending on their economic situation, in an interest-bearing account they can access at 18. When Hillary Clinton was running for president in 2007, she proposed the government do the same here, to the tune of $5,000 per newborn. In short order, then-Republican front-runner Rudy Giuliani lambasted her—another big spending liberal program!—and Clinton didn’t have the stomach to enter the fray. She dropped the proposal, a harbinger of things to come; we now know that presidential elections are where innovative ideas go to die.

But state and local treasurers have learned from the Baby Bonds flameout eight years ago. Most do not require any public investment (though Massachusetts is about to pass a program that might include public dollars), and, while it’s still too early to determine how much universal college savings accounts may fuel college attainment, it’s clear that the movement speaks to something in the zeitgeist. “This illustrates the defining characteristic of 2016,” Torsella says. “The action is not coming out of Washington. It’s states and cities that are innovating and making progress. The same story is true, by the way, when it comes to climate change and green energy. Just ask Michael Bloomberg where change is happening.”

“The research shows that children with a college savings account are anywhere from 4 to 7 times more likely to attend college,” says Torsella. “It’s about saying to kids, ‘Our expectations for you are high and yours should be, too—you are a college-bound kid.’”

We hear a lot nowadays about authenticity in our candidates. Remember when conventional wisdom was that George W. Bush was “real” because you wanted to have a beer with him? Now we hear that Donald Trump is “real” because he belittles people in his campaign to be Narcissist In Chief. But there’s another, more complicated type of authenticity, the kind that is emotionally transparent about one’s motives. I am reminded of this when Torsella bolts upright in his chair, eyes widening, after I ask him if donors share his passion for his big idea —or if he can sense cynicism on the other end of the phone when he’s dialing for dollars.

“They do!” he fairly shouts. “Not all of them, but many. And I can’t not talk about this. My campaign staff tells me to shut up sometimes. But the idea that by holding this office, I could give every kid in Pennsylvania a college savings account and change some of those trajectories, and change their relationship with money and bend the income inequality curve? That’s why I get up in the morning. On a day that’s full of the part of politics I don’t look forward to, the necessity of spending hours and hours asking people for money, that’s what I tell myself and that’s what makes me smile. I often say to the campaign team I want to have a conversation with someone about this idea and learn more about it every day, not because it does something for the campaign, per se, but because it’s what I need to do to be passionate about being in the campaign.”

To spend an hour with Torsella is to come face to face with this very rare type of authenticity, at least in our political life. It’s driven by ideas, a sense of history, and intellectual curiosity. In the course of a single conversation, he holds forth on corruption in our state’s public life—“It’s a sad commentary that our bar for elected office is don’t get in trouble, don’t embarrass us; it’s pathetic”—and delves into a plan to borrow an idea called Ohio Open Checkbook, where every dollar of state spending is made so transparent online that it makes the citizen a de facto auditor.

Then he’s onto a short history lesson, tying together four Pennsylvanians—James Wilson (“He was, by the way, an immigrant, which is one of the things I love about him.”), Thaddeus Stevens, former Governor Gifford Pinchot and Andrew Carnegie—in a narrative that illustrates the idea of a Commonwealth. And then he’s off on a communitarian spiel that serves as the philosophical underpinning for all he believes. “We’re one of four states to call ourselves a Commonwealth,” he says. “That word means something to me. The words I always come back to in thinking about my politics are words like Commonwealth and, especially, We The People. We haven’t always lived up to those words, but they speak to our best self.”

Joe Torsella pauses, and I wonder if he’s about to catch himself. Politicians don’t often speak about the ideas that inspire them—perhaps because so many are inspired by little more than the attainment of power for its own sake. The consultants might tell him there’s a risk in being so open, that there’s such a thing as too much authenticity. After all, Torsella, an accomplished fundraiser with a broad base of insider support, could likely win without introducing any creative, problem-solving plans. But he’s running to govern, not just to win.

So now he’s onto another story, his story, the story of a kid from the tiny hamlet of Berwick, Pennsylvania about an hour outside of Wilkes Barre, whose maternal grandfather ran a junkyard and paternal grandfather immigrated from Puglia, Italy with two brothers and, according to family lore, one pair of shoes among them…and that kid went to Penn, Oxford and became a UN Ambassador. But he didn’t do it alone—do we ever? No, there were financial aid packages, student loan programs, and—most importantly—expectations placed upon him.

“I feel I went through my life with a sort of whole town saying to me, ‘We’re counting on you, you’re going somewhere, and how can we help?’” Torsella says, his voice cracking. “I think where we are today, there’s not enough of that. There are too many lives that don’t have that. I get that the time and place I grew up in doesn’t exist anymore. Berwick isn’t even the same anymore. When I was growing up, the guy who ran the plant was in the same bowling league as the guy who worked there. And he got paid 33 times what his employee made, not—what is it now? Between 300 and 400 times? So what I want to do for our century is create new versions for that kind of support I felt.”

Joe Torsella pauses and smiles. He’s come full circle. “I guess what I think we need politically is a big dose of ‘We,’” he says.

Photo header: Flickr/Tax Credits