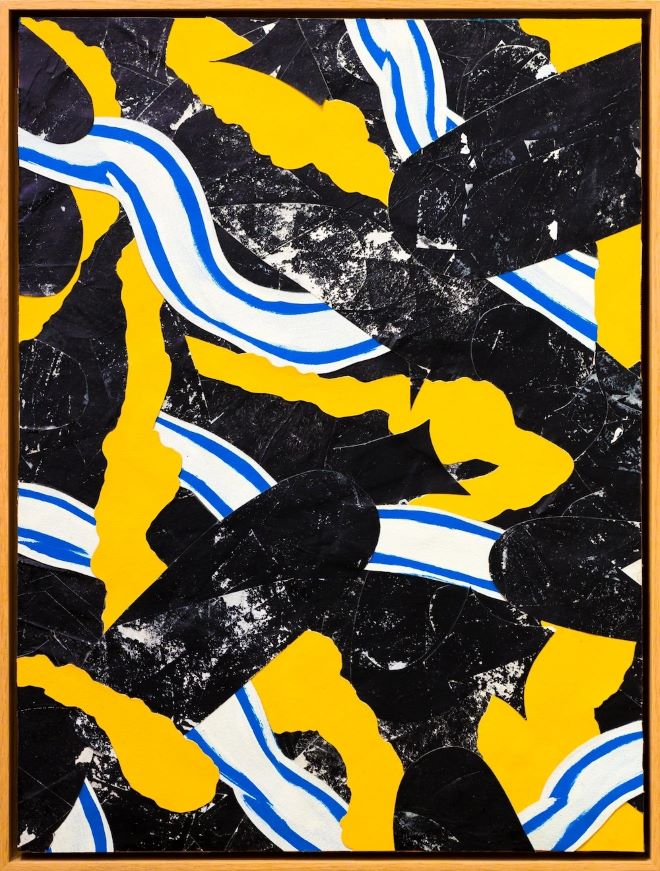

After growing up in Portland and spending time in New York City, the artist Nick D’Auria (NDA) has been in Philadelphia for just under a decade. His West Philly home pulls double-duty as his studio, which allows NDA to pick up a brush or a jigsaw whenever inspiration hits. His cartoonish abstract paintings and sculptures that can be enjoyed equally by a toddler or their grandparent. They bring to mind Roy Lichtenstein’s oversized Brushstroke Group sculpture (installed at 17th Street and Ludlow Street) with a bit more silliness to it, and certainly more approachable. These are serious works of art, when you consider that fun is serious business. Equal parts self-deprecating and intuitive, NDA has said, “[I] start making marks until something comes together.”

At All Parts, NDA’s solo exhibition at Paradigm Gallery, his kooky, colorful, and sometimes a bit DIY assemblages fill the gallery’s second floor practically to overflowing. The show is anchored by an immersive installation made up of dozens of strips of painted canvas hung from the ceiling and woven together or placed at criss-crossing angles. The assortment of colors, patterns, and shapes gives the feeling of stepping inside of the artist’s messy (but fascinating) brain. The rest of the show is riffs on that patchwork, with collages (largely) drawn from scraps of experiments undertaken by NDA during the dullness of the early Covid-19 lockdowns.

All Parts is open at Paradigm Gallery in Old City through August 25. The exhibition features paintings, sculptures, and prints by NDA.

As part of a partnership with Forman Arts Initiative, The Citizen caught up with NDA. The interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

RJ Rushmore: How are you feeling about All Parts?

NDA: Surprisingly good. All Parts started as an opportunity to reinstall My Dream Walked on Four Legs, Pushing Air, which was originally shown at the Philadelphia airport in 2021. And then Paradigm Gallery suggested I should include all this work that had been made around the same time as that piece. This is largely work that I made to keep myself busy during the pandemic, and it is nice to put those pieces into a more official context.

For anyone who may have seen it at the airport, how is this reinstallation of My Dream Walked on Four Legs, Pushing Air different?

I am really happy that this version feels like it’s a part of the same universe, but another iteration. The space is different, so I had to come at it in a new way. At the airport, the piece was enclosed in a glass vitrine. At Paradigm, I have a lot more room to play. When you come into the space, I wanted to create an almost overwhelming cascading feeling. With the gallery’s high ceilings, we were able to give a feeling as though the work was crashing over on you. And then you get to walk around the piece and discover calmer moments. We found all these interesting little spots, but I like the very back of the piece because it is a contrast to the initial intensity. It’s quieter from there, even though that’s an odd thing to say about an installation made up of big, giant, loud pieces.

Active participation seems like a big part of this piece. This is a chance for visitors to explore an artwork, not just view it.

It goes further than exploration. With anything immersive, the presence of a viewer changes the work. When a large group is walking through an installation, the silhouette of one person walking on the other side of the room becomes part of someone else’s viewing experience. That leads to unexpected discoveries, like if the pattern of a person’s shirt briefly interacts with the piece and inspires me to incorporate that pattern into a future iteration.

I’m doing 50 percent of the work, the audience is doing the rest of it, and I don’t really get to choose how that goes. Embracing that sort of happenstance is freeing.

When you’re making a multi-piece installation or a collage, how much are you planning out in advance? Is everything sketched out, or are you making those modular components separately and seeing what fits together?

I try to embrace accidents and serendipity. It keeps me surprised. With this show, I had an assortment of collage elements that I’d made without any thought of how they were going to go together, and I turned those into a fun challenge for myself.

Oftentimes, pieces would get stacked up on my studio floor. I’d spot a nice combination of things in one pile or another, and I’d take a note of it. It was a lot of embracing happy accidents. In the past, I have made a goal for myself and gone straight from A to B to C, and I think this approach is more successful.

When you’re cutting a piece of wood, what’s the process for making a great squiggle?

With wood, there’s none of that improvisation. You make a mistake, and you’re going to be spending a lot of time fixing it. As a result, I’ve gotten pretty good with a jigsaw. I like cutting wood, it is very meditative for me. Except for the stress of making a mistake. That part can be nerve-wracking.

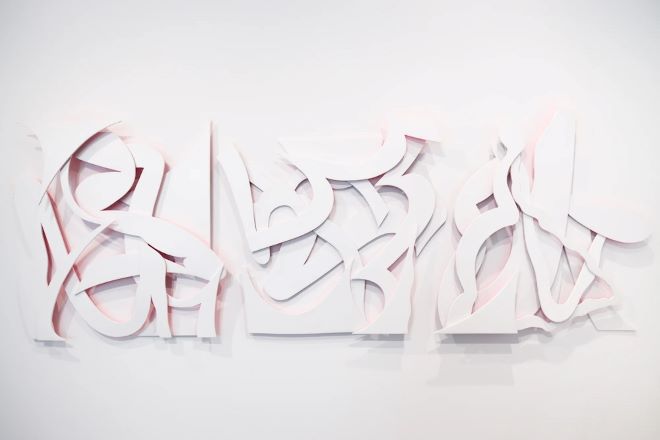

Some of my favorite pieces in All Parts are the Louise sculptures, which are abstract combinations of cut wood. When you and I spoke at the exhibition’s opening, you told me that this series involved a “cheap trick.” What did you mean by that?

Those could have worked well as subtle white pieces, but I wanted some extra oomph. I painted the back of each element fluorescent pink, which gives the idea that the artwork is glowing. This is basically just the poor man’s version of expensive neon lighting behind the piece to give it some backlight. The fluorescent paint does the job just fine.

It definitely does. It’s also maybe better than electric lighting. The fluorescent paint is so subtle, and you didn’t arrive at that end result the obvious way. I had to get up close and investigate what was going on, and I spent more time with the artwork as a result.

A little bit of mystery can be fun, and I definitely enjoy doing a thing that achieves the same goal as something more expensive and more fancy.

Where did your interest in DIY hacks like that come from? It sounds like it’s not just out of necessity, but also maybe curiosity or to challenge yourself.

Growing up, we didn’t have a lot of fancy stuff, but my parents always figured out ways to be creative. My mom was a dancer, and my dad designed sets for small town theater productions. Those theater budgets were always small, but he made it work. So I’ve been influenced by their resourcefulness. I don’t necessarily think that the most expensive way is the right way. Sometimes, if you sit down and think on it for a bit, big problems have creative solutions, and I enjoy that challenge.

The flip side is that I have always been someone whose technique is a little bit wrong. If I’m interested in something, I don’t necessarily need somebody to show me how to do it. And I don’t say that to sound pretentious or edgy. For example, I’m not drawing the right way. I tend to knuckle drag a bit, and it’s really hard for me to ink something without making a mess. I’ve kind of come at it my own way, right or wrong.

I think it works, even if you’re doing it wrong.

RJ Rushmore is a writer, curator and public art advocate. He is the founder of the street art blog Vandalog and culture-jamming campaign Art in Ad Places. As a curator, he has collaborated with Poster House, Mural Arts Philadelphia, The L.I.S.A. Project NYC and Haverford College. Rushmore’s writing has appeared in Hyperallergic, Juxtapoz, Complex and numerous books. He holds a B.A. in Political Science from Haverford College, where his thesis investigated controversies in public art.

This story is part of a partnership between The Philadelphia Citizen and Forman Arts Initiative to highlight creatives in every neighborhood in Philadelphia. It will run on both The Citizen and FAI’s websites.

![]() MORE FROM OUR ART FOR CHANGE SERIES

MORE FROM OUR ART FOR CHANGE SERIES