There is a common misconception that “political” art has to be literal or simple to be understood — like a protest poster, Shepard Fairey’s Hope or Barbara Kruger’s Your body is a battleground. That same argument, though, is not something you hear much about literature or music. Does Beyonce’s cover of Blackbird not have political implications?

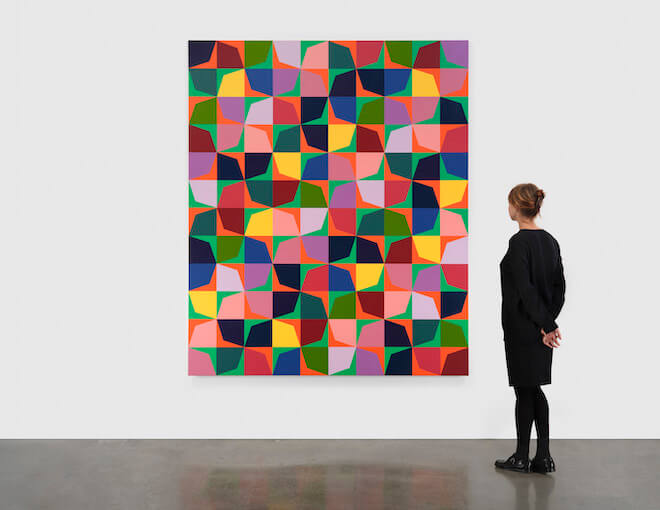

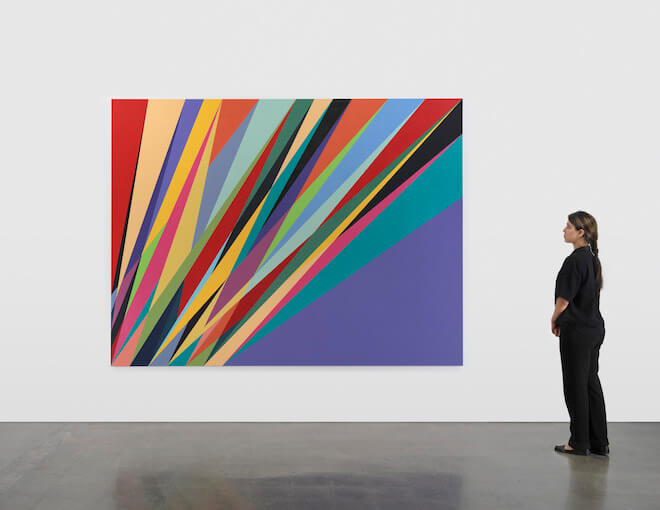

Odili Donald Odita is an abstract artist whose paintings comment on very concrete social and political struggles. Among the most well-regarded abstract artists working today, his paintings and installations consist of colorful geometric patterns. The colors, the shapes, and (in the case of the installations) how everything is placed within the larger context of a space, are thoughtfully designed and meticulously executed to tell a story. For example, shapes fitted together like puzzle pieces might represent a history of specific community groups that have held a neighborhood together for decades.

It can be difficult to place Odita. He was born in Nigeria, left at six months old and was raised in suburban Ohio. He’s both a professor at Temple University’s Tyler School of Art and Architecture and a working artist who exhibits at some of the most prestigious art galleries and fairs in the world. (Visiting Odita’s studio recently, he was preparing to send multiple paintings to Switzerland for Art Basel.) His aesthetic influences range from African pattern to minimalism to comic books. Perhaps it’s that hodgepodge that has led Odita to make work that is equally at home in highbrow institutions as it is in an NFL stadium.

Currently, Odita’s painting Place can be seen at the Brooklyn Museum, as part of the museum’s hit new exhibition Giants: Art from the Dean Collection of Swizz Beatz and Alicia Keys. That exhibition is open through July 7.

As part of a partnership with Forman Arts Initiative, the Citizen caught up with Odita. The interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

RJ Rushmore: You have described your paintings as relating to the history of civil rights, the Movement for Black Lives, and various other societal struggles. To start, can you explain how those complex ideas get expressed in your abstract paintings?

Odili Donald Odita: In a certain way, I’m making a visual graph. For instance, I had an installation at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 2021. That piece was like a schematic of the placement of people within a space. I was interested in some very powerful imagery of people outside of the museum and along the Parkway, staging protests during the pandemic. Folks were squatting in the fields across from the museum to protest the affordable housing shortage. Other people were speaking out against police brutality. In that piece, I tried to draw on visual information from photographs of those protests.

I don’t believe in the idea of abstraction in the most basic sense. I can understand it if I read it in a dictionary, but everything to me is real. I feel it as real. If it’s a red painting and somebody says “Anger” or “Blood” as the title, the word brings up so many associations in my mind. I love how information can trigger all those things inside the body, which all feels very real to me.

At the PMA, I wanted to make a space that had rhythms and movements, sections of light and dark, and things that people would maybe emotionally respond to as they walked along the length of the wall.

And I wanted it to be beautiful because I think beauty is an important aspect of art. Beauty is about an undeniable space and it has an undeniable effect. Make something that you can’t turn your back on and you can’t turn your face away from. I think that’s useful when you want to make a statement that’s as grand and as gorgeous as ending police brutality.

You have installed a lot of large-scale murals. Just thinking about Philly, there was the Philadelphia Museum of Art, but also the Comcast Technology Center, the Brandywine Workshop and Archives, and the Penn Medicine Pavilion. How do you think about bringing your art into existing environments?

Early in my practice, I watched more established artists fly like rock stars into these exhibitions, to just come in and leave. I asked myself, “Where’s the connection to the venue they’re working at?” When I started to be asked to do installations, I wanted to learn about the place I was working, because that would help me with the content. How else was I going to have meaning? I didn’t want to make something that was meaningless. Now, I keep two challenges in mind: What can a painting do in this place? and, How am I bringing my knowledge of this place into the painting?

What kinds of locations are interesting to you?

I’ll be doing something at Dallas Cowboys’ AT&T Stadium. I want to be able to explore nontraditional spaces and not feel limited by the idea of where art is expected to belong. Instead, I want to think, “Wow. Let’s see what’s possible here.” The term is play. Let’s play here, see what we can do, see what we can make out of it, and let’s play in a way that’s creative and evolving and brings other people in. That’s exciting because you’re in a conversation with more than just yourself.

Your painting Place (2018) is currently on display at the Brooklyn Museum as part of their exhibition Giants: Art from the Dean Collection of Swizz Beatz and Alicia Keys. That’s a blockbuster show bringing together world-class Black artists like yourself, Derrick Adams, Kehinde Wiley, and so many others. How’s that experience been?

It is great to be in that company. Importantly, it’s a “for us, by us” exhibition. As collectors, Swizz Beatz and Alicia Keys are supporting living artists who would be, in essence, their peers in another discipline. It shows to Black people: We’re taking care of our own, and we’re showing it in the best way possible. These people are alive, and this is the voice of today. I think that’s what makes the show so important to people.

And the way they’ve presented this work, it’s very open. They wanted to show it like it was in your house.

Throughout the galleries, there are speakers playing music and couches to sit on, little spaces to chill.

Exactly. The art feels accessible. Giants is a pop show for sure. It has broken attendance records and reached a lot of people. That is really important because the art world has generally cultivated this feeling of being rarefied and elite. Now, smart museums are trying to become more open to people from all walks of life. Museums are expanding beyond being, let’s say, collections of war and conquest.

How do you feel about your own art in relation to pop culture?

I think my work is very pop. Over the years, I’ve come to understand that high and low are two sides of the same thing. You can’t ignore one or the other. The high is in the low, and the low is in the high, and you can look into the low and bring it up high. You have spaces of refinement, but you also need to look in the world. And the world can be a messy place, but that’s the source.

That so-called source, that messy place, is a seedbed for great contemplation. Before you arrive at something clear and beautiful and have your thoughts realized, you have to sift through all this messy reality. It came from somewhere. Let’s acknowledge that.

So when I say, “I’m pop,” what I am saying is that I come from a common field of the human experience, and I want my ideas to also come back to the people who work in the common field of human experience. Even if I’m engaging in some high positions of aesthetic consideration, I want it to be real.

RJ Rushmore is a writer, curator and public art advocate. He is the founder of the street art blog Vandalog and culture-jamming campaign Art in Ad Places. As a curator, he has collaborated with Poster House, Mural Arts Philadelphia, The L.I.S.A. Project NYC and Haverford College. Rushmore’s writing has appeared in Hyperallergic, Juxtapoz, Complex and numerous books. He holds a B.A. in Political Science from Haverford College, where his thesis investigated controversies in public art.

This story is part of a partnership between The Philadelphia Citizen and Forman Arts Initiative to highlight creatives in every neighborhood in Philadelphia. It will run on both The Citizen and FAI’s websites.

![]() MORE FROM OUR ART FOR CHANGE SERIES

MORE FROM OUR ART FOR CHANGE SERIES