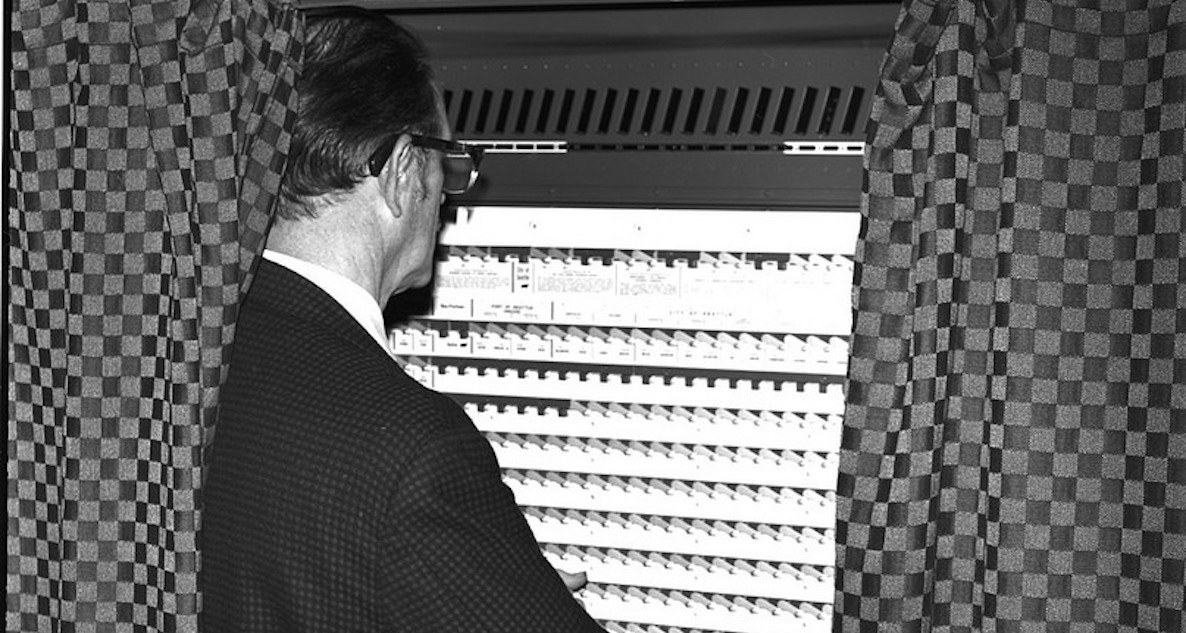

Do you believe that Court of Common Pleas judges, who are responsible for deciding major civil and criminal trials, and family and domestic issues, should be chosen completely at random, by fishing a ping pong ball out of a coffee can? If so, you’re going to love Philadelphia’s upcoming judicial primaries.

In a new post at the Sixty Six Wards blog, Jonathan Tannen explains the problem with these no-information races, and why the effects like ballot position tend to swamp other factors.

The field for Common Pleas is huge; we don’t know how many openings there will be this year, but in the five elections since 2009, there was an average of 31 candidates competing for 9 openings. Even the most informed voter doesn’t know the name of most of these candidates when she enters the voting booth, and ends up either relying on others’ recommendations or voting at random. This is exactly the type of election where other factors—flyers handed out in front of a polling place, the order of names on the ballot—will dominate.

Because of this low attention, some of the judges that do end up winning come with serious allegations against them. In 2015, Scott Diclaudio won; months later he would be censured for misconduct and negligence, and then get caught having given illegal donations in the DA Seth Williams probe. The 2015 race also elected Judge Lyris Younge, who has since been removed from Family Court for violating family rights, and just in October made headlines by evicting a full building of residents with less than a week’s notice. In 2016, Mark Cohen was voted out as state rep after reports on his excessive use of per-diem expenses. In 2017, he was elected to the Court of Common Pleas.

Every one of those candidates—Diclaudio, Younge, and Cohen—was in the first column of the ballot.

Defenders of judicial elections will often try to cast the debate in populist terms, arguing that judicial merit selection is elitist, doesn’t completely eliminate politics, and that for all the known problems with electing judges, we’re still better off with voters choosing judges directly.

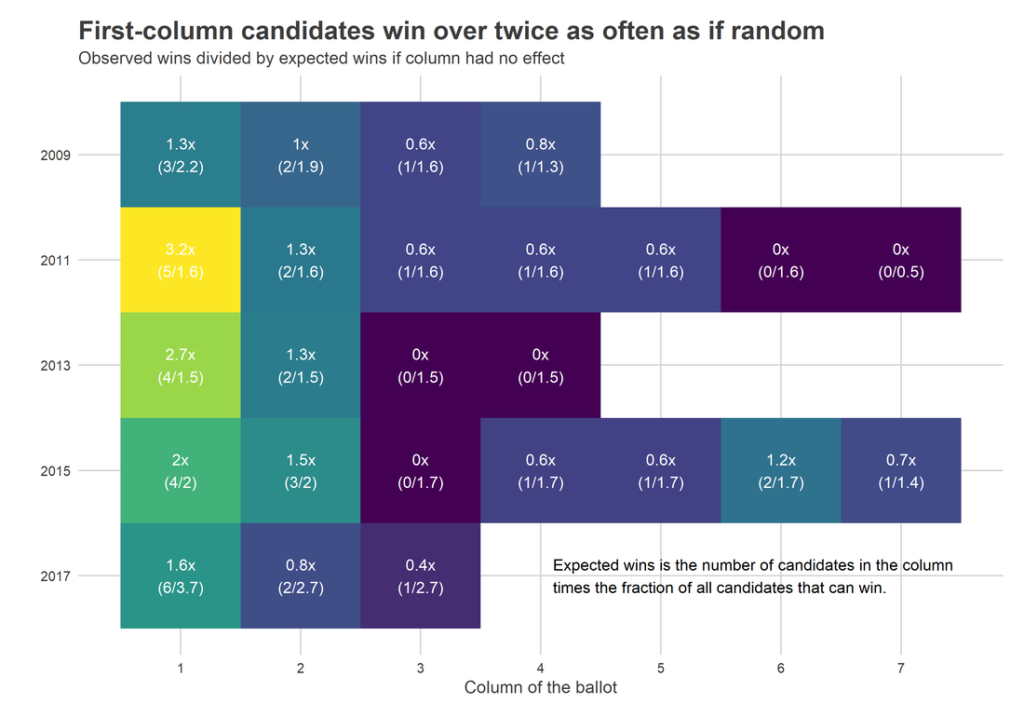

The problem is that the current system, where ballot position is so lopsidedly determinative of the winners, is missing any kind of intentionality about who is being hired for these 10-year positions. Tannen shows pretty definitely in the post that candidates are disproportionately selected from the first column on the ballot, and that several recent unqualified judges had first column positions in their elections:

“[C]andidates do win from later columns every year. But first-column candidates win more than twice as often as if all columns won equally. Below, I collapse the columns for each year, and calculate the number of actual winners from each column, compared to the expected winners if winners were completely at random. The 2011 election marked the high-water mark, when more than three times as many winners came from the first column than should have.”

It’s true we’ll never eliminate politics from being a consideration in judicial merit selection, but at a minimum, there’s at least going to be some rhyme or reason to why attorneys are going to be promoted to judgeships, and depending on who’s doing the appointing, if they’re an elected official they’re going to have reasonably good political incentives not to appoint totally unqualified people to the bench.

![]()

In judicial elections, or at least in the way they’re conducted in Pennsylvania, voters have almost no useful information about who the candidates are and what kinds of decisions they’d make, and—since most voters aren’t informed about the legal profession—no real ability to evaluate the candidates’ professional qualifications either.

This goes back to the issue of voting machine procurement too, since the easiest way to remove the ballot position effect is, as Tannen says, to randomize ballot positions in each division throughout the city.

It would require a change to the state Election Code to do this in Philadelphia, but it would also require us to have voting machines with the technological capability to randomize ballot position, or allow voters to rank their choices, and that decision is going to be made very soon.

Jon Geeting is the director of engagement at Philadelphia 3.0, a political action committee that supports efforts to reform and modernize City Hall. This is part of a series of articles running in both The Citizen and 3.0’s blog.