Last week, in response to Mayor Kenney’s annual address to the Greater Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce, I wrote about the apparent dearth of innovative job creation strategies coming out of the Mayor’s office. Nationwide, I posited, cities have become engines of economic growth by being laboratories of experimentation. Here, we seem wedded to a lot of old-school tax and spend, redistributive thinking. I looked around and highlighted some ideas that seem to be working elsewhere and asked: Why not here?

I didn’t even mention how, by ignoring the common sense prescriptions of not one but two tax reform commissions, we’ve disadvantaged ourselves when competing with other cities and suburban counties for talent and jobs. Now comes a new report that brilliantly lays out the degree to which we’ve long been our own worst enemy when it comes to growing the local economy, and that reiterates the transformative effects of reforming our tax system.

Philadelphia: An Incomplete Revival, released last month by the Center City District (CCD), both diagnoses and prescribes. I caught up with Paul Levy, president and CEO of CCD and long one of our most thoughtful policy minds. It was Levy, along with Brandywine Realty Trust CEO Jerry Sweeney, who put together the diverse group calling itself the Philadelphia Growth Coalition—a mix of Democrats and Republicans, labor and businessmen leaders—which has made real progress agitating for increasing commercial property taxes by 15 percent and dedicating those additional revenues to lowering wage and business taxes. The idea is to decrease taxing what can move—people—and increase taxing what can’t—buildings.

Larry Platt: Your report does a great job of laying out the current state of things. Can you summarize where we are in terms of economic growth?

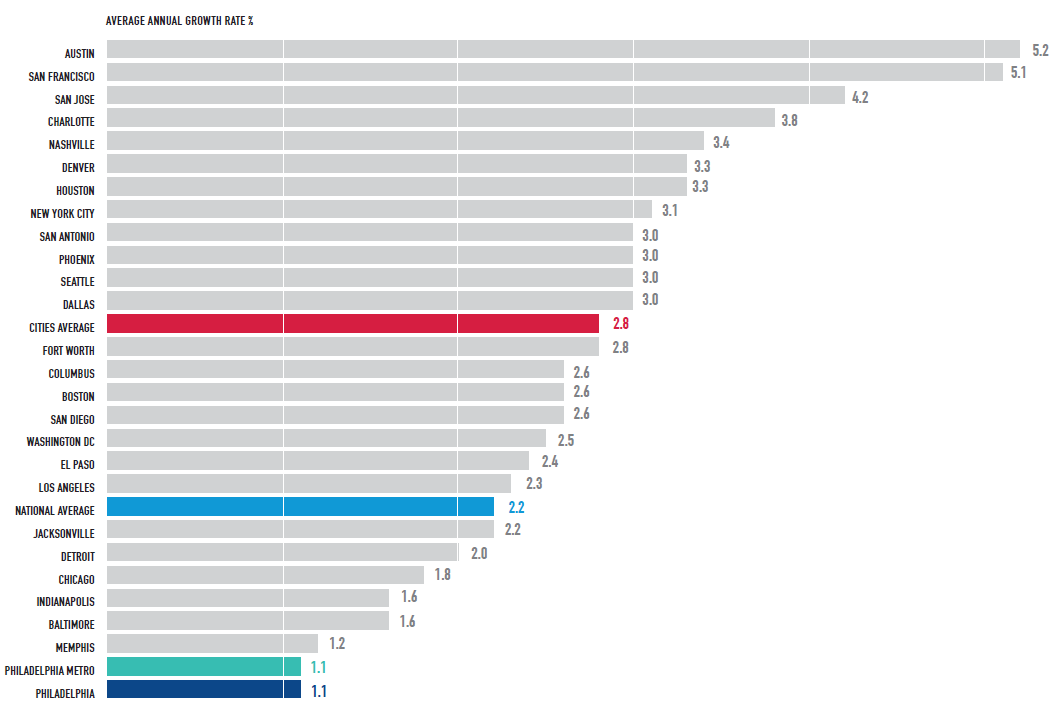

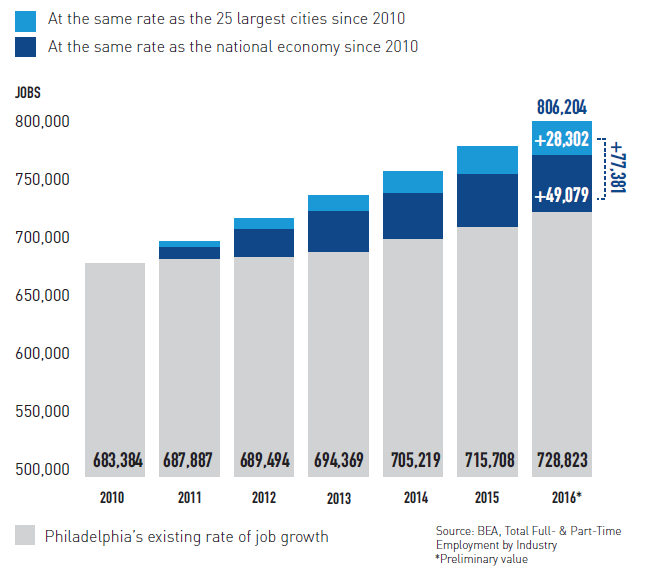

Paul Levy: First, you’re right when you say that cities have outperformed the national economy since the Great Recession. The 25 largest have grown at 2.8 percent between 2010 and 2015, compared to 2.2 percent nationally. But Philadelphia’s growth is at 1.1 percent. That’s slower growth than we see in Detroit and Baltimore. That may seem out of sync with what we see in Center City and University City, but that’s why we call this An Incomplete Revival.

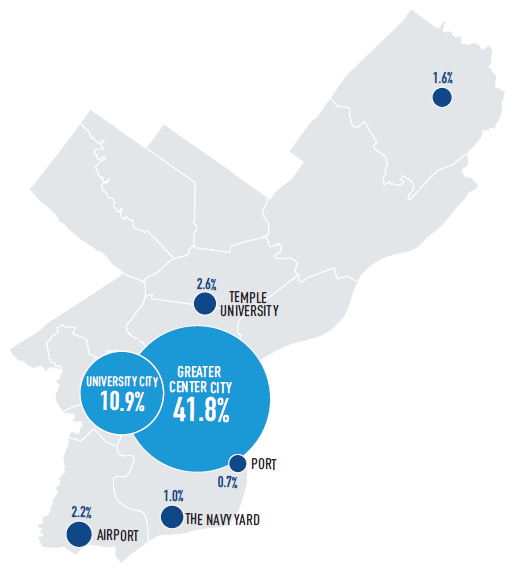

LP: In fact, the report points out that over half of all jobs are in Center City and University City. But that wasn’t the most surprising statistic. The number of those making a reverse commute out of the city stunned me.

Levy: Yes, 39 percent of city residents are reverse commuting to jobs in the suburbs. In New York, for example, that number is at 15 percent. And it’s not just Center City young professionals. A huge number of people in North Philadelphia and Olney are taking the Broad Street Line and the 125 or 126 bus out to the King of Prussia Mall to work retail jobs. They’re traveling an hour each way. It’s not that they don’t have the energy or commitment to work. We just don’t have the jobs here for them.

LP: You mention young professionals. Many of us—and I may be guilty of this—have hyped Philadelphia’s influx of millennials. How meaningful is that demographic change?

Levy: It’s a really good thing. But it’s a misreading of the data if you think it’s going to be transformative—because it’s time limited. We’ve already passed the peak of the Millennial trend, which happened in 2015.

LP: And that Pew report a few years ago found that many of them feel that, if we don’t fix the schools, they’ll be off to the suburbs in a few years.

Levy: Actually, people remember it that way, but they actually listed job growth first and schools second as the reason they might ultimately leave. Let me find it here. [Shuffling papers.] Yes, here it is. The top two reasons you expect to leave the city: 38 percent said jobs/career and 29 percent said schools. Only 10 percent said they’d leave because they’d prefer the suburban lifestyle. This is a moment of great opportunity for Philadelphia, because we’re a city with so many incredible amenities. We’re walkable, affordable, vibrant. But we’re at the bottom of the pack in terms of job growth.

LP: The report lays out the challenges we face in having the nation’s highest poverty rate (25 percent) and highest child poverty rate (38 percent) in the nation. But it also explains how that came to be and links it to policies that have stymied job growth.

Levy: That’s right. Our poverty rate is terrible, but it’s not that the actual number of people in poverty skyrocketed. It’s that so many working-class and middle-class residents left the city. Between 1970 and 2000, the number of middle-income residents who moved out of the city was 12 times greater than the number of residents added to the poverty rolls during that time. Had we not had a loss of a half-million working-class and middle-class residents during those three decades, our poverty rate would have been 17 percent in 2000 instead of 23 percent. That’s a big difference.

LP: And that gets us to the idea that our tax policy has helped fuel that loss to the suburbs.

Levy: We’re not suggesting that tax reform is a panacea. But there’s no question that our tax structure has been pushing jobs out of the city. Think about this: If you’re living in Philadelphia and working in King of Prussia or anywhere in the suburbs, you’re paying a wage tax of 3.9 percent. If you move close to your job in the suburbs, you get an automatic pay increase of almost 3 percent because most counties have no more than a 1 percent earnings tax. So the wage tax creates an incentive for workers to decamp from the city. And employers will tell you it impacts them as well, because they have to increase salaries to compensate for the wage tax if they want to attract workers who live in the suburbs.

LP: In recent years, Philadelphia has seen its first population growth since the 1960s. But that doesn’t mean we’re still not losing people to the suburbs, right?

Levy: Correct. Philadelphia’s population grew because births outnumbered death in the city and we benefitted from a new wave of international immigration—something that is seriously challenged today. Domestically, we see the 5,000 in-movers per year from Montgomery County—the millennials and empty nesters. But what we don’t see are the 10,000 residents each year who decamp to Montgomery County. And, yes, the millennial surge is great. But for all the focus on them, the fact is if you take out immigrants, we’d still be losing population.

LP: Clearly our tax structure harkens back to a time when the city could tax wages because the jobs were here. But now, in the most mobile of societies, we’re still taxing what can move. Where do we stand with amending the state Constitution so we can tax commercial property at a higher rate?

Levy: Last summer, HB 1871 was passed by the General Assembly. It needs to pass again this year before it can be placed on the ballot for a vote. We feel good. We’ve got the mayor’s support, and in the next couple of weeks we hope to move forward with him and a coalition of Democrats, Republicans, labor and business leaders. This doesn’t tie the city’s hands; it allows us to compete.

LP: It’s a long slog to amend the Constitution.

Levy: I jokingly say to people, we’ve made it over the Appalachian Mountains, I can see the Rockies in front of us, and the High Sierras in the distance. But we’re moving forward.

Photo header: Flickr/Jamesy Pena