Yami was just 17 when she was arrested and sent to the adult jail on State Road in Philly. With federal law requiring that minors be separated from adults in adult facilities, Yami was held in solitary confinement — for her “protection.”

Over the course of the nine months she awaited a hearing, she had no interaction with peers. Her only interactions at all were generally through the bars of her cell, or during the very limited and insufficient time she had out of her cell for education, or to shower or make an evening phone call. Pregnant when she entered the facility, upon giving birth she was separated from her own child, per the protocol of adult prisons.

“Children do not belong in adult jails and prisons. Children are not adults,” Fine says.

“She was functionally isolated from anyone else in her age group, and really from anyone else, period,” explains Lauren Fine. Fine is the co-founder, with fellow attorney Joanna Visser Adjoian, of Youth Sentencing & Reentry Project, or YSRP. The women launched the nonprofit in 2014 with their unwavering belief that children like Yami simply do not belong in adult jails. Philadelphia has sentenced more children to life in prison — to die in prison — than any other city in the world.

Among other things, YSRP provides children sentenced to life in prison, and their families, with free legal support; in addition to providing this kind of direct service, they use policy advocacy to transform the experiences of children prosecuted in the adult criminal justice system, and to ensure fair and thoughtful resentencing and reentry for individuals who were sentenced to life without parole as children.

RELATED: Philly won $1 million from Bloomberg Philanthropies for a Juvenile Justice Hub

In Yami’s case, that looked like convincing a series of judges involved in the case, over the objection of the prosecution, that instead of staying at the jail, Yami should get the support she needed. At the time of her arrest, the teen — who had been in foster care — was squatting in an abandoned home; the father of her child was a 32-year-old co-defendant; she was also heavily under the influence of drugs and alcohol and had no recollection of the incident.

YSRP successfully got Yami into a mother-baby drug and alcohol treatment program, where she was reunited with her child to learn parenting skills and get treatment for her substance abuse issues. They helped her connect back to school; she ultimately graduated from Youth Build Charter High School with a 99 percent attendance rate and excellent relationships with the teachers and administrators. She subsequently moved to Florida, where she now lives and is employed and pursuing post-graduate education while raising her family.

“Instead of throwing her away, the system was willing to consider a more unique approach, a healthier approach,” Fine says. “Her trajectory is a testament to the power of young people to accomplish their own goals when given the right structures and support, and a better form of justice.”

“Yami is living a life that would not have been possible had she been sentenced to adult prison. Instead, judges were willing to be open minded to a different way of moving forward that actually addressed her situation, her needs, and the community’s needs as well,” Fine says. “Instead of throwing her away, the system was willing to consider a more unique approach, a healthier approach. Her trajectory is a testament to the power of young people to accomplish their own goals when given the right structures and support, and a better form of justice.”

For their dedication to young people like Yami and countless others, Fine and Visser Adjoian — who this month are beginning the process of passing the torch to new YSRP leaders — have been named to Generation Change Philly, The Citizen’s partnership with Keepers of the Commons to highlight and support Philadelphians who are making a meaningful difference in our communities, and in the future of our city.

Deeply-rooted beliefs

Visser Adjoian and Fine have always had a heightened sense of the world’s inequities.

“The movement for social justice and racial justice has been central to my identity, to how I exist in the world as a biracial Black woman,” says Visser Adjoian, who grew up in Mexico City, Maryland,and New York City, and came to Philly, which she considers home, in 2000 for college. “I’ve always been aware of persistent structural inequity and inequality.”

She’s also the daughter of an immigrant and says she “understood early on the way that systems operate on the lives of people who don’t have equal access to resources and opportunity and power.”

Fine, meanwhile, grew up in the Philly suburbs with what her family might describe as a heightened, almost preternatural, awareness that she and her White peers were consistently treated differently than her peers of color — in her public school, on sports teams, wherever. “I was always questioning the privilege that I had, and felt like I was a participant in a system that didn’t actually promote fairness,” she says.

It was during law school — Fine at Duke, and Visser Adjoian at Penn — when their vision for converting that passion into action started to crystalize. Fine helped to create a program at a youth detention center in Durham, NC, through which she and peers brought lyrics and poetry to the young people there every week. “It was a space for them to speak out loud and have community with the other young people around them, and it became so clear to me how much brilliance and potential we were throwing away.” It cemented for her a path that she was already on, she says.

“Every time I left the prison, I knew I had been the student, and the people inside were the teachers–not the other way around,” says Visser-Adjoian.

Visser Adjoian, meanwhile, spent her law school weekends visiting SCI Graterford (now SCI Phoenix) teaching classes to the men who were incarcerated there. “Every time I left the prison, I knew I had been the student, and the people inside were the teachers — not the other way around,” she says. “As these very privileged students, we felt that we had all of this wisdom and knowledge and that we were doing a service, but really we were receiving the gift of being exposed to these wise, kind, funny, complicated people. That for me was the most foundational education I experienced.”

That the two women’s paths would cross soon thereafter, as young lawyers working at Philly’s Juvenile Law Center, was fortuitous — and formed the basis for what would become YSRP.

“The impetus for YSRP was the learning that we did in the spaces with loved ones and those who were themselves sent away as children — families who had gone through the torturous experience of watching their loved one sent away and told they would never leave prison,” Fine explains. And so it was on a car ride the two women took across Pennsylvania in 2013, en route to a women’s prison, that they started formulating the idea for YSRP with these central questions:

What would a more holistic model of advocacy look like for children who are prosecuted as adults, for those who are sent away presumably for life? And what would it mean to support them upon their return to the community, at whatever point that might happen?

From the start, the women’s work has been informed by the experiences of young people who’ve been incarcerated, and their families. YSRP partners with court-involved youth and formerly life-sentenced children, their families, and lawyers to get cases transferred to the juvenile system or resentenced, and make crucial connections to community resources providing education, healthcare, housing, and employment. They also recruit, train, and supervise students and other volunteers to assist in this work.

RELATED: An innovative Police Department program works to upend the schools-to-prison pipeline

Their ultimate goals: to keep children out of adult jails and prisons, and to enhance the quality of representation formerly life-sentenced children receive at resentencing, and as they prepare to reenter the community. They serve all of their clients for free, with funding primarily from foundations and individual donations, and one major corporate source of support. Recently, they applied for and received their first government grant.

“Children do not belong in adult jails and prisons. Children are not adults,” Fine says. “And this is really a crucible moment for our city in understanding how we want to show up, how we want to be as a city. This is a moment when our city can choose to do something different. I have a lot of trepidation, but also a lot of hope.”

Societal shifts

In the course of their work, the women have seen meaningful shifts: In 84 percent of YSRP’s youth cases, they prevented a young person from going to adult prison. To date, they have worked with 71 youth from Philadelphia, Delaware, and Montgomery Counties, and have walked alongside 42 “Juvenile Lifers” through their resentencing hearings — for 31 of them, through their return to the community.

They have provided advice or reentry support in an additional 85 cases. On top of that, they have provided training at 21 State Correctional Institutions, on mitigation and reentry for folks sentenced to die in prison as children, leading to the creation of the PA JLWOP [Juvenile Life Without Parole] Database. They’ve launched three cohorts of Intergenerational Healing Circles, including one for women and girls. And in 100 percent of cases where they submitted a mitigation report, the prosecutor or judge cited it in making their case determination.

RELATED: Could this reentry program be a key to less gun violence in Philly?

Since they began their work, they’ve also seen the U.S. Supreme Court rule that judges must consider mitigating circumstances before imposing a life-without-parole sentence. That ruling did not eliminate life-without-parole for children, or the possibility that children are detained or sentenced to adult jails and prisons. On any given night, there are still between 10 and 15 teenage boys and girls under the age of 18, who are sleeping at the adult jails on State Road (a substantial decrease from years past), Fine explains. The same is true in other places outside of Philly, around the Commonwealth.

But the other meaningful shift that the women have watched has been central to their decision to, at the end of this month, step down as leaders of YSRP. That shift? The rise and recognition of voices from directly within and adjacent to the experience of being incarcerated.

“What makes me feel the most hopeful is the leadership of the young people and the [formerly life-sentenced children] who we’ve had the privilege of working with,” Visser Adjoian says. “They are at the forefront of the most meaningful change that has happened and has the potential of happening. And that is a direct connection to the decision we’re making about leadership change, because we see the vast and deep potential that exists [and] that isn’t always leveraged in these movement spaces.”’

RELATED: A lawyer and advocate calls for ending our expensive culture of incarceration

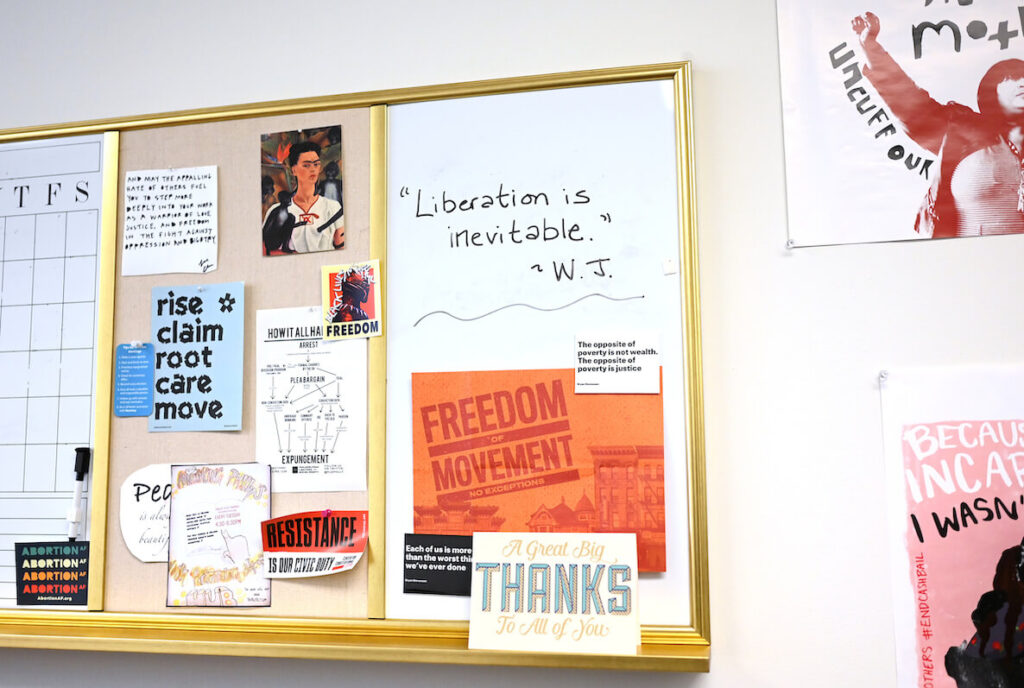

The women see daily reminders of the power of voices from within, and adjacent to, the incarceration experience — in organizations like Youth Art and Self-Empowerment Project (YASP), and in coalitions of young people and youth advocates like Care Not Control, which seeks an end to youth incarceration, which they helped launch and continue to help lead.

“Lawyers don’t have all the answers in the legal system,” Fine says. “And we’ve been inspired by the idea that partnership in many forms — working across lawyers, social workers, folks who come to this with lots of different life experiences and especially lived experience — can push each other to think differently about what has always been done, and what can be done differently.”

“We feel very strongly that those who are leading us out of these crises — those who are bringing the imagination and the capacity to create real change — are those who are closest to the problems themselves,” says Visser-Adjoian.

“It’s all there, right in front of us, if people actually take the time to pay attention and listen to those who are most directly impacted by all of the systems we’re talking about,” Visser Adjoian says. “The conversation has really shifted: It really does feel like there is more of a reckoning happening. But there’s so much more that needs to happen.”

Change is essential

When the women step down later this month, YSRP will name an interim director as its board searches for the organization’s long-term leader. Fine is expecting a child in February and is likely to pursue a new opportunity starting in September; Visser Adjoian will join the Philadelphia-based social impact organization Spring Point Partners as Senior Program Officer, Social Justice. (Spring Point, which funds YSRP, also supports The Citizen.)

“What makes us hopeful is the community of people that have shown up to care about this issue,” Fine says. “That includes young people and family members who have direct experience with the justice system; that includes people who have only academic or intellectual understanding of these issues and have been moved to join us and to understand that this is in all of our names. It has been really inspiring to feel like there’s a growing interest in unpacking some of how we got here, and where we can go collectively.”

Visser Adjoian says change isn’t just exciting, but essential.

“Challenging the status quo is really important,” Visser Adjoian says. Over-surveillance of Black and Brown and poor communities, leading to mass incarceration, has not made those communities safer, she notes. “We have to take a different approach, we have to be more imaginative as a community when we’re faced with these kinds of crises and not just dig into what has never worked in the past. And we feel very strongly that those who are leading us out of these crises — those who are bringing the imagination and the capacity to create real change — are those who are closest to the problems themselves.”

The Philadelphia Citizen is partnering with the nonprofit Keepers of the Commons on the “Generation Change Philly” series to provide educational and networking opportunities to the city’s most dynamic change-makers.

![]() MORE ON CRIMINAL JUSTICE REFORM

MORE ON CRIMINAL JUSTICE REFORM

The Philadelphia Citizen: Local News With Solutions and Action

The Philadelphia Citizen: Local News With Solutions and Action

The Philadelphia Citizen: Local News With Solutions and Action

The Philadelphia Citizen: Local News With Solutions and Action