The Kenney administration, 1st District Councilmember Mark Squilla, and preservation advocates released the final recommendations of Mayor Kenney’s 33-member Historic Preservation Task Force this week, and their top actionable priorities point to an appealing vision for how we can have both more preservation and more housing that’s very much in keeping with the new politics of zoning remapping that I’ve written about previously.

The Kenney administration and Councilmember Squilla are committing to the following agenda items, according to yesterday’s release. Caitlin McCabe reports:

Among the city’s most significant plans: Establishing a citywide survey to document Philadelphia’s historic properties, creating an “index” of non-historically designated buildings that cannot be demolished until there is a heightened review, and introducing a zoning bonus for developers who contribute to a new Historic Preservation Fund […]

Many of the other proposals released Thursday will depend on how quickly Squilla’s bills move through City Council. In addition to legislation to allow for zoning bonuses, he plans to introduce a bill that would reduce parking requirements for historic buildings that are redeveloped. Another bill would increase the ability for developers to redevelop properties “by right” — meaning under their current zoning designation — if they are “special purpose” historic buildings such as churches and schools.

In addition, Squilla, who represents the city’s First District, which includes the Society Hill and Old City neighborhoods, plans to introduce a bill that would create two new types of historic districts for neighborhoods, including some of Philadelphia’s “middle neighborhoods,” which may want to see historic properties preserved, including some of their own homes, without having the typical rules and regulations attached.

The full document is about 67 pages long and has dozens of recommendations too varied to summarize here, but there are several interesting policies worth mentioning that would support more housing creation instead of depressing it, would be free or cheap to adopt, or would only require a one-time expenditure of political capital by the Mayor and City Councilmembers to take the side of preservation in cases where there’s a trade-off with localized concerns over parking or density.

By-right zoning for special purpose buildings

By-right zoning means that if a proposed project abides the underlying zoning rules assigned to it, the builder can simply pull an over-the-counter permit and build it. Oftentimes so-called “special purpose” buildings like former schools or churches are zoned for something other what the most plausible reuse scenario is for them, so reuse proposals end up having to apply for a zoning variance, which is much more discretionary and politicized, and presents project opponents with a much clearer path to killing the thing.

The political coalition for historic preservation has included an unfortunate ‘Not in My Back Yard’ contingent that’s simultaneously in favor of protecting historic buildings, while also opposing pragmatic trade-offs on issues like housing density or parking in order to save buildings.

This change could have preempted the whole controversy over St. Laurentius in Fishtown where, because the proposed reuse of the historic church building didn’t conform to the rules of its assigned zoning classification—RSA-5, which allowed one single-family home—it was forced into the more discretionary variance process where it was subsequently held up for years by legal appeals.

Read the full task force reportDo Something

The Task Force is proposing that City Council “amend the zoning code to allow any permitted use in historic buildings within CMX1, CMX2, CMX 2.5, CMX 3 (and perhaps other districts) zoning areas, if the developer commits to rehabilitating the building,” although the Historical Commission would still need to vote on approval.

The City wants to start with “special purpose” buildings like schools and churches for this, but it should really be expanded to include any former warehouse or industrial buildings too, since those are much more common.

Eliminating parking minimums for adaptive reuse

The Task Force report notes that “[p]arking requirements add significant cost to development projects both because of the cost to construct the parking and because the need to provide parking limits the flexibility of design” so they propose either reducing or eliminating parking minimums for historic buildings.

Articles by Jon Geeting Read More

As with the by-right reuse recommendation, this should be expanded to any reuse project, not just those projects designated historic. The report notes that this may be the current practice in some situations, but there are some important loopholes to close to make sure parking minimums never prevent historic or adaptive reuse projects.

The most important scenario is change of use. It’s true that the current amount of parking available in a building is grandfathered in, meaning that as long as there is no use change proposed, the statutory parking requirements are waived. But when a proposed project triggers a use variance—say, from industrial to residential—that’s when mandatory parking requirements could still kick in and give opponents an opening to NIMBY the plan to death. Parking should never be the reason not to save a building, and Council should revise the code text to ensure parking minimums are never triggered for reuse of any existing buildings.

Allow accessory dwellings by-right

One way to fight against the economic incentives that exist in some places to tear down perfectly good historic buildings is to create a supplementary income stream for historically designated properties by allowing accessory dwellings.

Accessory Dwelling Units, often referred to as ADUs, or sometimes granny flats or backyard cottages, essentially allow a second dwelling within the same building or property footprint as the principal dwelling, turning single-family zoning into duplex zoning, effectively.

The zoning reform bill of 2012 passed language allowing for Accessory Dwelling Units, but then Council never specified which zoning districts they’re allowed in, thanks to lobbying by Republican 10th District Councilmember Brian O’Neill.

ADUs should really be allowed anywhere they’ll fit, including in rowhouse neighborhoods where there are sometimes surprisingly deep lots, but the Task Force report, for now, is recommending that they be “permitted by-right for properties in all defined categories of historic districts,” reasoning that “ADUs will provide revenue to homeowners to help maintain the building.”

More types of districts with varying flexibility

One reason why historic preservation is at such a disadvantage in Philadelphia is because the preservation battles are almost always at the level of individual buildings, rather than broader historic districts. Historic districting has been out of favor here for various reasons for many years, one of which is that some residents rebel at the idea of empowering Homeowners Association busybodies to dictate what kinds of doors, windows, and other details their homes should have.

There are several interesting policies that would support more housing creation, would be free or cheap to adopt, or would only require a one-time expenditure of political capital by the Mayor and City Councilmembers.

In recognition of this, the Task Force is recommending the creation of a new tiered system of historic districts with lighter-touch regulations that can be tailored to provide more flexibility to property owners while still preserving key buildings and architectural details that make a neighborhood unique.

Zoning bonuses for historic preservation, or funding contributions

Thematically similar to the new Mixed-Income Housing program, another proposal in the Task Force report would create a new density bonus in the zoning code for historic preservation:

Philadelphia Zoning Code contains Floor Area Ratio (FAR) bonuses that allow developers to increased density in RMX-3, CMX-3, CMX-4 and CMX-5 districts. The code offers several bonus options, including public plazas, affordable housing, and other amenities. Proposed Change: We propose that the City adds historic preservation as a zoning bonus option. If a property developer agrees to rehabilitate one or more historic buildings or contributes to the Historic Preservation Fund, the developer will receive a bonus. The historic building or buildings do not need to be located near the parcel receiving the bonus.

They suggest that the bonus should be allowed to “be combined with other bonuses…up to the maximum permitted” to maximize the impact. As with the Mixed Income Housing program, this idea has the advantage of creating money out of air, as it costs taxpayers nothing to create new legal permissions to build more units. Insofar as funding has been a major obstacle to preserving more buildings, this proposal could go a long way toward creating a revenue stream for preservation.

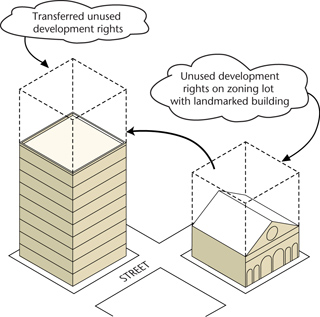

Transferable development rights

Transferable development rights are a policy we’ve advocated for in the past, so it’s great to see this included in the Task Force recommendations. The simple explanation is that development rights have a monetary value that’s capitalized into a property’s overall value, so historic designation, by curtailing (re)development rights, reduces a property’s value under normal circumstances.

This is an argument that some preservation advocates tend to be defensive about, likely out of a belief that acknowledging this fairly obvious reality would put their agenda at a political disadvantage with the way designations are done today, where development rights are essentially destroyed in the course of the historic designation process.

There isn’t any good reason why the development rights need to be destroyed though, and the idea behind creating a transferable development rights policy framework is that it should be possible to sell any unused development rights from over top of an historic property, and let someone else spend them building taller or denser somewhere else. That could be on another nearby site, or it could be in some other areas where officials want to prioritize higher-density development, like near transit stations, or perhaps in the new qualified Opportunity Zones.

(Image: NYC.gov)

By allowing historic property owners to sell the unused “Floor Area Ratio” over top of their properties, the City could create a new revenue stream for preservation, and also ensure that preservation never has to come at the cost of new housing supply, since the development rights could be recycled into other projects. Here’s what the Task Force recommends:

We propose that the City develop a TDR program that allows historic building owners to transfer development rights, e.g. allowable gross floor area, to other projects. Implementation of a TDR program is technically and politically challenging and may not generate significant interest citywide, depending on demand for new construction and density. A TDR program is similar in concept to a zoning bonus, but administratively more complex. This incentive rewards private capital for investing directly in historic preservation.

What kind of political coalition could make these changes happen? Hint: It’s not the current one.

It’s a bit of an over-generalization, but to date, the political coalition for historic preservation has included an unfortunate ‘Not in My Back Yard’ contingent that’s simultaneously in favor of protecting historic buildings, or just neat old buildings, from demolition, while also opposing pragmatic trade-offs on issues like housing density or parking in order to save buildings. And in many cases, people who are principally motivated by NIMBY concerns will borrow the rhetoric or the regulatory tools of preservation to block housing. One way of thinking about it is that it’s a coalition of preservationists and landowners versus developers.

Judging by the dismal results in terms of their effectiveness at getting a critical mass of buildings preserved, it’s clear this coalition isn’t really getting much traction, and that preservationists are getting much less out of the marriage than the NIMBYs are. So it’s refreshing to see the outlines of a new coalition that could be formed around these new priorities: an unholy alliance between the more pragmatic architecture-focused preservationists and preservation-minded developers that cuts the NIMBY landowner interests loose.

A coalition like that could work together to make historic designations a net financial benefit to builders in more instances, in contrast to the status quo, and to lobby for zoning code text amendments that put many more historic and adaptive reuse projects on the glide path to permitting, avoiding the more discretionary and politicized variance application process, and winning more funding for preservation in the process from new zoning bonuses and development-rights auctions.