It is election time again in Philadelphia, a season where condescending attitudes over the average voter return with all the regularity of the swallows of Capistrano.

A large subset of Philadelphia’s politicians and media buy into a persistent and pernicious myth that Philly voters are a mix of the indolent, the injudicious and the iniquitous; that many elections are won by buying the right ward leaders and union bosses with job promises, even when they show no promise for city jobs.

It is assumed that voters, universally and always, will do precisely as they’re told by little pieces of paper handed to them by a stranger hanging out next to the polls.

There are plenty of bygone reasons for these foregone conclusions about Philly’s sheep-like electorate. But more recent events and a serious look at the assumptions underpinning this viewpoint make it as untenable as it is unattractive.

Consider the largely negative responses last October to then-candidate Tom Wolf’s proposal to replace the appointed School Reform Commission with an elected school board, a proposal that Nelson Diaz has endorsed and that some other mayoral candidates haven’t completely shut the door on yet.

Other candidates, notably Jim Kenney and Tony Williams, say they believe the school board should remain appointed. Their argument was best made by that éminence grise of Philadelphia political reporting, Dave Davies: “Establishing an elected school board in Philadelphia will not empower parents and their communities. It will put the selection of our school board members in the hands of the same people who pick judges, state legislators, sheriffs and city commissioners in this town: Democratic ward leaders.”

Davies was echoing former School District Interim CEO Phil Goldsmith: “As for democracy Philadelphia-style, all you have to do is look at the meager turnout for our municipal races to realize that our elections are largely determined not by the ‘people’ but by a handful of power brokers…. If you want to get a glimpse of what the Philadelphia School District as envisioned by Wolf might look like, consider the composition of City Council and row offices like sheriff or the city commissioners.”

Why do so many assume that an elected school board will be nothing more than party hacks who will do as they’re told? It’s more likely that we would see more political antagonism than cronyism. An elected School Board would be puissant, not pusillanimous, in its exercise of political power.

It’s no accident that both men focused on row offices like sheriff and city commissioner, and that Davies mentioned judges—Philadelphia has elected some top-notch losers to fill these seats.

The election of row offices and judges fails what James Madison called the “aim of every political constitution” in Federalist No. 57, namely: “first, to obtain for rulers men who possess most wisdom to discern, and most virtue to pursue, the common good of the society, and in the next place, to take the most effectual precautions for keeping them virtuous whilst they continue to hold their public trust.”

By electing city commissioners – who run city elections—we’ve gotten one who doesn’t bother to vote, and another who failed to get on the ballot. By electing sheriff, we have an office associated more with FBI investigations than competent service. And when it comes to judicial elections—a problem statewide, not just in Philly—we’ve gotten crooks and the incompetent, undermining faith in our judicial system as a whole.

But before we simply give the Philly Shrug again and lament our general democratic ineptitude, it’s worth asking a simple question: Why?

Why can’t Philadelphia elect someone competent to these offices? Is there something wrong with us? Are we still so “corrupt and contented” as Lincoln Steffens so famously wrote over a century ago?

No. Madison offers the real answer: These aren’t the failings of Philadelphia’s society, so much as a failing of our “political constitution”: These are particularly terrible offices to fill via elections.

Elections work best when the electorate has both the motivation to pay attention and the means – when there is sufficient media attention to allow average voters make informed decisions. America’s best election is for President: Voters have an idea of what the President does and they generally understand the differences between the candidates thanks to copious amounts of media coverage. In Philadelphia, registered voters understood the difference between Mitt Romney and Barack Obama, and 66 percent of them voted in 2012.

But as we work our way down the political ladder, both motivation and means drop, and voting rates drop with them. The consequences seem less dire, even if the electoral math means your vote is more valuable. If you voted for President Obama, you were voting for universal health care, to bring back the troops, more regulations of Wall Street, and more. If you vote for Councilman Oh, you’re voting for breast-milk pumping protection, a small tax credit for veterans, and…. a singing contest?

Consider the row offices: city commissioners, sheriff and register of wills. All are purely administrative offices. They don’t set policy of any kind, so there is no need to directly hold a democratic check over these offices. As a result, the voters lack pretty much any motivation to pay attention to these posts, provided they are run with some minute modicum of effectiveness. (There’s a reason why the people that rail against the city commissioners and sheriff largely ignore register of wills: Ronald Donatucci has managed the office quietly and apparently well.)

It’s only when something goes wrong that the voters might notice, but even there, the means are limited. It isn’t that voters are incapable of voting against someone like City Commission chairman Anthony Clark, who doesn’t even bother to vote himself – let alone show up to the office. But since I first wrote about his pathetic voting record, I’ve counted no more than ten news items about it.

That may sound like a lot, but it really isn’t. It’s a story easy to miss – somehow, despite my shameless self-promotion on Facebook and Twitter, lots of my friends didn’t hear about it. And if Clark wasn’t so ridiculously lazy, there would be even fewer stories; maybe a few editorial board endorsements would have called him out, but who knows? Even when the commissioners screwed up running the 2012 election, it didn’t directly affect many of us (and those it did were still able to vote using provisional ballots).

Or consider judges, which are even worse. Even most lawyers are in no position to judge our judges: I’ve been to court once in my nearly four years as an attorney. Individual cases, especially civil cases, rarely make headlines. And when judges claim they’ll be tough on crime or fair to the little guy, that’s an unsalvageable corruption of their very raison d’etre—to be the impartial arbiters of justice—that should disqualify them out of hand. But even then, voters really have little reason to care: Most will never face trial personally. Even if we did, we would need a trial attorney to tell us if we should be upset with how the judge ran her courtroom.

For all of these offices, we completely lack motivation and means as voters to make good decisions.

But no one talks about voter apathy when it comes to education.

Thirty-two percent of residents named education the top issue facing Philadelphia, according to a recent Pew survey, making it by far the most important issue in this election. Even though our mayor and City Council don’t have much say over schools, it’s the one issue voters keep asking them about. Philadelphians are motivated to pay attention to this issue: It indirectly impacts the regional economy and directly affects their kids. Consequently, Philly voters also have the means: SRC meetings are often front-page news here.

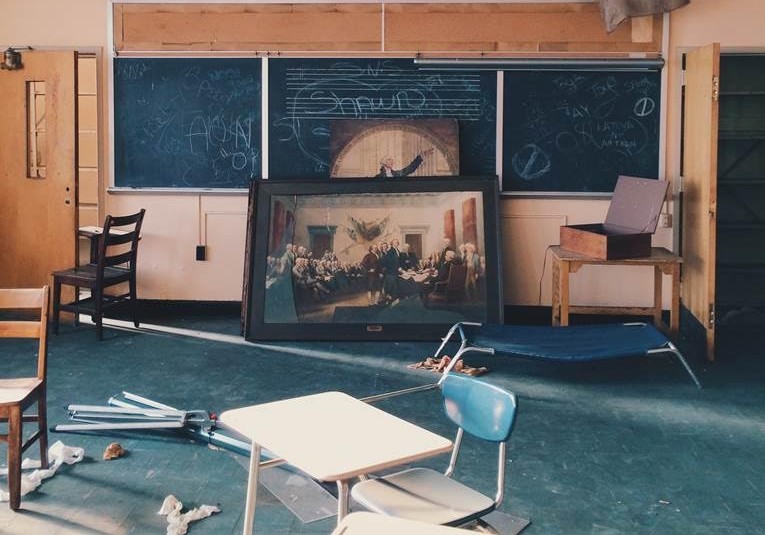

And parents don’t need to rely on newspapers to tell them how the schools are. They hear about the deplorable conditions from their children. They know first hand, from PTA meetings and teacher visits, how cramped the classrooms are.

Consider a finding from a recent piece by Stephen St. Vincent: “Since 1987, 31 incumbents have run for re-election, and 27 of them have won—an 87 percent success rate.” That certainly sounds high, but it’s relatively low: 95 percent of Congress won reelection in 2014, a historically consistent result—despite an approval rating that hovered around 14 percent.

It turns out, Philly voters are better than average at throwing the bums out.

So why do so many assume that an elected school board will be nothing more than party hacks who will do as they’re told? It’s more likely, as evidenced by City Council’s recent thumbing its nose at Mayor Nutter’s plans to sell PGW—or, indeed, raising taxes to increase the school budget—that we would see more political antagonism than cronyism. The School Board would be puissant, not pusillanimous, in its exercise of political power.

The assumption that the teachers union would come to dominate the board is equally specious. Pro-charter groups recently offered the School District $25 million if it opened more, and have spent millions in support of Tony Williams’ gubernatorial and mayoral campaigns. And most Philadelphians support charter schools.

Of course, electing a school board won’t magically fix things—Philadelphia schools have many challenges, including needing more money, which requires a better funding formula from the state.

Regardless, four to one Philadelphians support scrapping the SRC and nearly two-thirds of those would support electing a school board. Philadelphia should let them.

Why Philadelphians can be trusted to elect a competent school board