A couple weeks ago in The Citizen, we ran a story by Mastery Shoemaker principal Sharif El-Mekki, about a series of troubling interactions between the police and his students and staff after school. His Open Letter From a Principal to the Police sparked some debate, and also drew the attention of Commissioner Richard Ross, who then did something wholly unexpected: He picked up the phone, called El-Mekki and invited himself over to talk to Mastery students.

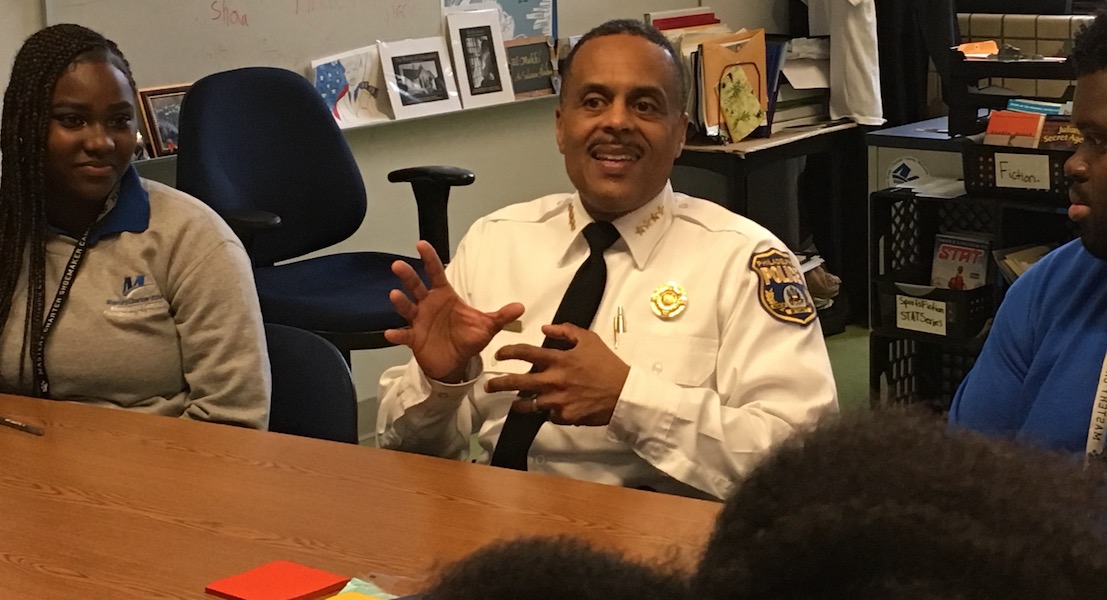

Let’s note at the outset that the very fact of this event is pretty remarkable. For about an hour, Ross sat at a long table with seven Shoemaker juniors and seniors, inviting them to ask him—the police commissioner of the fifth largest city in America—anything they wanted to know. They were an impressive group, all tilting towards college, with ambitions that ranged from nursing to chemistry to politics. They had made it to school, despite the SEPTA strike, by whatever means they could. And they were conscious of the moment, with bright sticky notes in front of them to write down their thoughts, in case they were nervous.

They also embodied the moment in other ways: African American teenagers in an all black school, from mostly black neighborhoods, with the fear and confusion that comes from living in times when police can seem as much, or more of, a threat than a help to young black people. Throughout their conversation, the kids asked Ross about police training (he wants to include a trip to the National Museum of African American History and Culture for every police academy class.); about why cops don’t try to get to know them (“Everybody is not the same as everybody else; they’re not necessarily outgoing.”); about how to approach police officers (“We’ve got to interact and see other as human beings,” including through police mentoring and athletic league programs, community days and other quieter moments).

Talking won’t stop the boys from automatically slowing their pace, and removing their hoods, when they see a police officer nearby when they’re on their way to school. It won’t stop the girls from wondering which is worse—walking home alone in the dark in their dangerous neighborhoods, or having a police officer nearby if something happens.

They tried to ask him about the events outside their school, when police officers caused a stir by riding their motorbikes up and down the sidewalk, and when they threw a 12-year-old girl into the back of a police car for having a “smart mouth.” Ross said he couldn’t talk about the specifics—but acknowledged the police have some work to do. “We have to find some common ground,” Ross said. “A lot of that is on the police. This is not an indictment of all police officers in this country, the lions share of whom do this job with the express intent of trying to protect people. The only way to make this country and this city better is we have to work together, for our safety and our humanity.”

As the meeting wore on, the students—respectful and poised—became quietly frustrated as they tried to explain how it is to be young and black in Ross’s city. As senior Katrina Bynum put it: “Police approach things wrong, and there are no repercussions. Most of our experiences are bad. For every 10 cops we encounter, there’s one good cop.” What, she wanted to know, are the police doing about that? Ross assured her that police are reprimanded regularly for illegal and unethical behavior. And he tried to assuage their worries that nothing will change.

“People ask me, Do black lives matter?’ Of course. I know what I look like, and that I’ll continue to look like this,” he said. “I’m also a police officer. Balancing all that out: I’m being honest enough to say we have so much to work on, but at the same time, if you have people fighting all the time we’ll never move forward.”

What Ross didn’t say—perhaps couldn’t, because of the presence of media and ![]() because of police politics—was that it is incredibly hard for even rotten police officers to be fired in Philadelphia; that while it is surely true that most cops are not intent on terrifying high schoolers, there is a deep cultural shift that must occur in this country for policing to be and seem just; that, in fact, police should not ride their motorbikes on the sidewalk, or throw 12-year-old girls into cop cars for having sass.

because of police politics—was that it is incredibly hard for even rotten police officers to be fired in Philadelphia; that while it is surely true that most cops are not intent on terrifying high schoolers, there is a deep cultural shift that must occur in this country for policing to be and seem just; that, in fact, police should not ride their motorbikes on the sidewalk, or throw 12-year-old girls into cop cars for having sass.

Those are the things that this group of students needed to hear. And afterwards—after posing for photos with the commissioner—they admitted that they were not so easily impressed.

“He didn’t really say much, just, ‘I got the police’s back,’” Jannah said. “He said, we’re put in a tough situation, the things we’re talking about date back a long time, and it could take a long time to get better.’

“He didn’t answer anything specific, just said the same things about having separate realities,” said Katrina. “I wanted to hear more.”

“People ask me, Do black lives matter?’ Of course. I know what I look like, and that I’ll continue to look like this,” Ross said. “I’m also a police officer. Balancing all that out: I’m being honest enough to say we have so much to work on, but at the same time, if you have people fighting all the time we’ll never move forward.”

One thing is true: A big city police commissioner taking the time to talk to seven young African Americans about policing and their experience is a commendable thing. It’s also hard to imagine how many such meetings Ross would need—and is willing—to take to really make a dent in how young black men and women perceive the police in their communities. Hundreds? Thousands? That’s a hard way to change hearts and minds, but Ross seems sincere in his willingness to get out there, filling a role that has not traditionally been part of a police chief’s job.

But it is also true that for these incredibly savvy students—and hundreds of young Philadelphians like them—talk is not enough. “I need to see more action from the police before I change my mind,” Tariq said later, while his friends nodded their heads in agreement. Talking won’t stop the boys from automatically slowing their pace, and removing their hoods, when they see a police officer nearby when they’re on their way to school. It won’t stop them from replaying in their heads the instructions from their mothers to announce everything they’re doing, loudly but politely, if a cop is nearby. It won’t stop the girls from wondering which is worse—walking home alone in the dark in their dangerous neighborhoods, or having a police officer nearby if something happens. “I don’t want to be a witness to anything,” Jannah noted.

And it doesn’t settle the fundamental quandary Jannah articulated for the rest in their conversation with Ross. “I feel like I can’t trust a whole group of people because I’ve seen them act on impulse with no repercussions,” she said. “Trust takes a lot of hard work.”