A new data analysis of requests for city-owned vacant lots from Ryan Briggs at WHYY clearly shows that Philadelphia’s vacant land problem is still very much a City Council problem, and that the Land Bank will never work while we still have Councilmanic Prerogative over land sales.

Prefer the audio version of this story? Listen to this article on CitizenCast below:

Audio Player

The conventional wisdom about Philadelphia’s vacant land issues for years has been that the city owns a lot of land nobody really wants because it’s concentrated in places with weak demand. So while it would be better not to have such a large inventory of vacant land for the City to maintain, in most cases there’s not going to be a willing buyer on the other side. And if there is, it may be somebody with no immediate plans to do anything with it.

That may have once been the case, but it was already moot as far back as 2016, when economist Kevin Gillen presented the land valuation model he created for the Land Bank with Guy Thigpen of the City of Philadelphia. Three years ago Gillen was saying a significant number of city-owned parcels were right in the path of growth, and given the continued upward trajectory in land prices, that’s almost certainly even truer today:

“Many city-owned land bank parcels are very tightly clustered around where values are growing, and historically speaking, the value is expanding outward from Center City,” he said. “So while these parcels may not be very large in terms of square footage, a significant number of them turn out to be right in the path of current growth, and the timing couldn’t be better.”

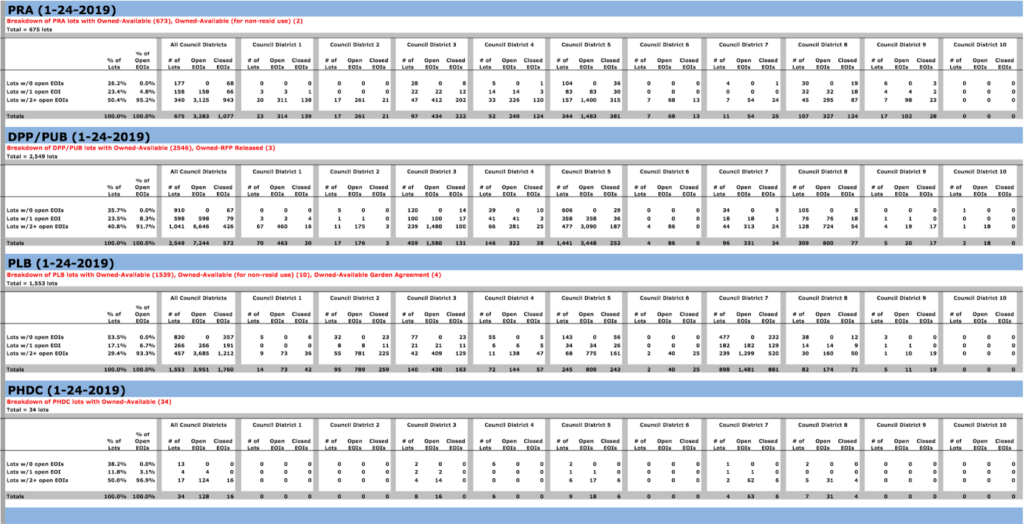

Now, a new analysis of Expression of Interest submissions to the Land Bank seems to corroborate this trend, finding that there are more people than ever trying to purchase some of the 4,000-odd city-owned lots, but the issue is that nobody’s getting back to them because of City Council’s iron grip on the disposition process.

The claim that Council is hard at work on a grand strategy to proactively use vacant land for higher and better priorities is just a bad joke meant to make it seem like they’ve learned their lesson. Don’t believe it.

The Land Bank has a “front door” website with their inventory of city-owned lots, where people can submit expressions of interest to buy land. But lots of people who have tried to use the site told Briggs it’s a black hole and the requests go nowhere. The only way to possibly get an answer is to go directly to City Council.

But city records and interviews with officials past and present indicate that the system never worked as intended and has rarely facilitated public sales.

The backlog of more than 18,606 applications includes submissions, known as “expressions of interest” as old as the portal itself, dating back to 2012. The vast majority of unresolved EOIs have been open for at least a year.

Meanwhile, few lots ever sell. Over the past fiscal year, the city’s inventory of 4,811 vacant lots decreased by a net total of only 78 properties—1.5 percent—as the result of sales.

At the current pace, it would take about half a century to sell off the fallow lots city officials consistently say they want to turn over for development.

Briggs talks to John Carpenter, a former deputy executive director of the Redevelopment Authority, who said that the big issue was that desirable parcels would always attract multiple expressions of interest, and Council and the administration couldn’t ever agree on who should win. And whenever they would consider the most direct way to resolve this—a public auction—they “found that almost every property had a backstory that generated pushback,” according to Carpenter.

It is clear that City Council is fully in the driver’s seat of the land sale process, and attempts by those Councilmembers to try and deflect blame to City staff are disingenuous.

The key to making progress, then, is to make all those “backstories” a non-factor by taking the people who really care about that stuff—District Councilmembers—entirely out of the approval process.

There’s nothing exactly surprising about these findings, but it’s politically relevant because it provides a more complete context on how something like the recent Kenyatta Johnson and Darrell Clarke land scandals were able to happen. It makes clear that City Council is fully in the driver’s seat of the land sale process, and attempts by those Councilmembers to try and deflect blame to City staff are disingenuous.

It also makes clear that to fix the problem, the Land Bank needs to have the power to do property disposition administratively, based on the goals laid out in their strategic plan, without discretionary political influence playing a role.

As we’re seeing this week, there are a lot of unmet priorities in the City budget, and a lot of programs and initiatives that people would like to see get more funding.

You sometimes see some distaste for the idea of simply selling city land to the highest bidder, since at least in theory there’s always the possibility that something of greater social value than a market-rate rowhouse or apartment building could materialize.

Clarke himself has been ignoring by orders of magnitude more EOI letters than any other Councilmember. There are 3,090 expressions of interest in his district alone, and Clarke’s District has nearly half of the city-owned vacant lots in it.

But two important benefits of that approach are that it eliminates the possibility of the sort of crony politics that Councilmembers keep getting in trouble for, and it also puts more money into the city budget, where lots of people always want more money for their favorite programs than they’re going to get. It does this both through the one-time revenue from the initial sale, and then on an ongoing basis through land taxes, which owners pay regardless of whether they immediately have plans to do something with the property or not.

Articles by Jon Geeting Read More

Darrell Clarke says this deprives the city of the ability to steer land toward hypothetically superior ends than simply having more cash for city budget priorities, like affordable housing or green space, but in practice, Council has had the better part of a decade to try and make that approach scale, and they haven’t made any progress. Meanwhile, thousands of lots remain out there collecting trash. Despite a handful of well-publicized workforce housing developments in his District, Clarke has barely made a dent in the stockpile of vacant land in his District.

And at the pace he’s going, he never will. Clarke himself has been ignoring by orders of magnitude more EOI letters than any other Councilmember. There are 3,090 expressions of interest in his district alone, and Clarke’s District has nearly half of the city-owned vacant lots in it.

One source familiar with the Land Bank’s internal processes says there are three districts where no land is ever allowed to be sold through competitive bid: the 3rd, 7th, and 8th District, represented by Jannie Blackwell, Maria Quinones-Sanchez, and Cindy Bass, respectively. They’ll let vacant lots sit forever so long as all buyers have to come kiss their ring first. Again, none of this is surprising because everybody already knows this is how it works.

And it means the claim in the incumbents’ platform that Council is hard at work on a grand strategy to proactively use vacant land for higher and better priorities is just a bad joke meant to deflect from their recent PR problems, and make it seem like they’ve learned their lesson. Don’t believe it.

Jon Geeting is the director of engagement at Philadelphia 3.0, a political action committee that supports efforts to reform and modernize City Hall. This is part of a series of articles running in both The Citizen and 3.0’s blog.