There was one moment several months ago with the South Philly community around Smith Playground that former Eagle and always civic philanthropist Connor Barwin will never forget. Barwin and his team from the Make The World Better Foundation stood before a packed room, presenting their plans to renovate the 7.5 acre park at 24th and Jackson streets. It included new baseball fields; a basketball court; a fitness hub; a renovated recreation center—opened last year—with a new kitchen and media center; two playgrounds; and an all-new, state-of-the-art, well-irrigated grass football field.

It was a grand plan, for which MTWB had raised all that it could—more than $2 million—and Barwin was excited to share it with the neighborhood. The community, though, was less pleased. Of course, they were thrilled that their vast park was getting a much-needed upgrade. But what they really wanted—what they had said from the beginning—was a turf football field for their South Philly Hurricanes that would not become a muddy patch after a few months of use. A turf field, though, was just not possible within their budget.

“People just looked at me, so sad, like, ‘That’s not going to work,’” Barwin recalls. “We left and I knew we had to find a way to make it happen.”

Barwin says he knows the ball fields will draw folks from all over the city, to play and watch. But he’s most excited about filling a need for the people for whom Smith can be a daily recreation spot. “We want to build these public spaces that are accessible to everybody in the neighborhood,” he says.

And find a way they did. Tomorrow, Barwin will officially open the new Smith Playground—including the shiny turf football field, on which the Hurricanes will hold a spring drills and skills practice in the afternoon. In total, MTWB raised around $3.2 million for the project, including $2.2 million from the City. The rest came from private donations, foundations, local businesses, the NFL and Barwin himself, who donated $150,000, matching the proceeds from his annual summer concert fundraiser in 2016, with Waxahatchee and Hop Along.

![]() “Everyone talks about finding ways to make these public-private partnerships work,” Barwin says. “This was a great success for that. Everybody worked together to make it happen.”

“Everyone talks about finding ways to make these public-private partnerships work,” Barwin says. “This was a great success for that. Everybody worked together to make it happen.”

Barwin—who wrote a column on civic issues for The Citizen for two seasons—started MTWB after five years of playing in the NFL, as the natural progression of a civic-mindedness that stems from childhood: His father, Tom Barwin, was the city manager of Hazel Park, Michigan, just outside Detroit; he is now the city manager in Sarasota, Florida. Barwin grew up not just with the notion that cities need to work for the people who live in them, but that the people who live in them need to work for their cities. Dinner table conversation was about sustainability, and public transit and smart cities. Before dinner, though, Barwin and his brothers were out of the house, in their neighborhood parks.

“When I was growing up, the neighborhood playground was a sanctuary for me,” Barwin told The Citizen in 2016. “Parks are the center of a community, a place that can really bring people together.”

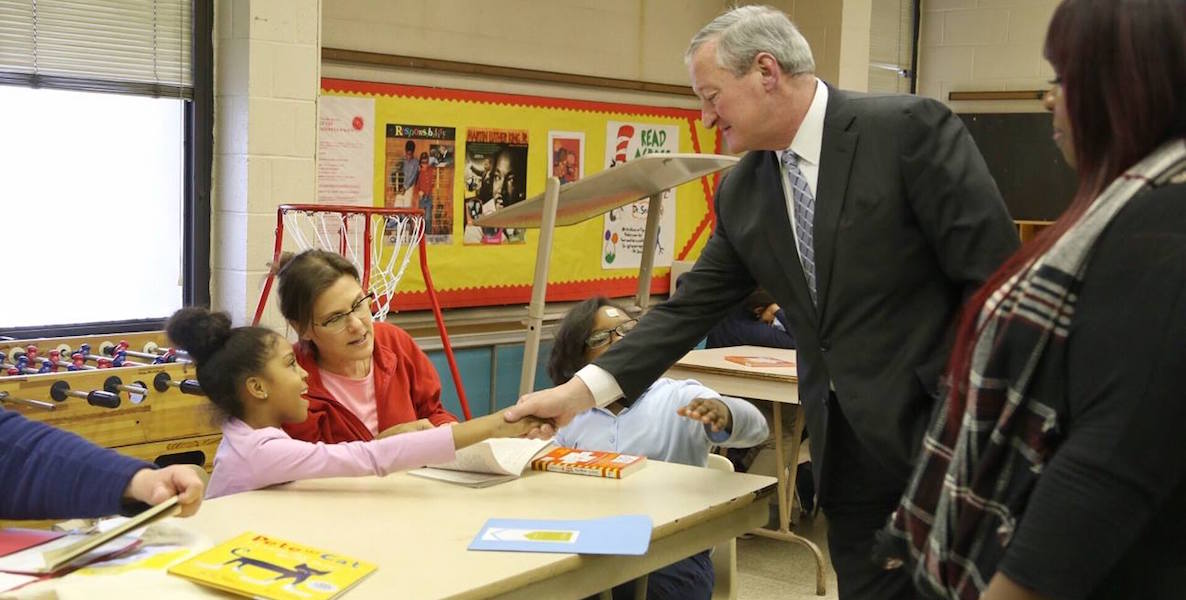

For the years Barwin played for the Eagles, he was the only player who lived in Center City, commuting to Lincoln Financial Field and around town on his bike, a recognizable urban dweller whose prowess on the field made Philadelphians listen to what he had to say off the field—about getting involved to do something, to make the world better. And he walked the talk: Barwin himself went to community meetings with MTWB, engaging with the neighbors to create a public space that they most needed. Now, in Los Angeles, his MTWB still operates in Philadelphia, and he still shows up when he can; he’ll be there on Saturday to open Smith.

![]() MTWB opened its first playground, Ralph Brooks Park in Point Breeze, in September 2015, on a series of vacant lots with a basketball court, a rain garden, a tot lot and several community gardens. The foundation will start construction on a third park—Waterloo in West Kensington—this spring. The $1.5 million for that project was raised in part by last summer’s benefit concert with War Against Drugs.

MTWB opened its first playground, Ralph Brooks Park in Point Breeze, in September 2015, on a series of vacant lots with a basketball court, a rain garden, a tot lot and several community gardens. The foundation will start construction on a third park—Waterloo in West Kensington—this spring. The $1.5 million for that project was raised in part by last summer’s benefit concert with War Against Drugs.

But Smith Playground is by far the largest project Connor and his foundation have undertaken—$3.5 million, 7.5 acres, three years to complete. Last spring, the foundation outfitted the new recreation center with a teaching kitchen and computers, in partnership with WHYY and the Tuttleman Foundation, doubling its size and allowing for robust out of school programming for neighborhood kids. In the summer, they opened the new basketball court, and playgrounds for toddlers and older kids. Tomorrow, they’ll unveil the final pieces: The new ball fields, and a bar park/fitness pod for teenagers and adults to exercise; the day’s events will include a bar competition.

Barwin says he knows the ball fields will draw folks from all over the city, to play and watch. But he’s most excited about filling a need for the people for whom Smith can be a daily recreation spot. “We want to build these public spaces that are accessible to everybody in the neighborhood,” he says.

Saturday, April 21st, 11 a.m.-3 p.m. (12:30 ribbon cutting; 2 p.m. bar competition), free, Smith Playground, 2100 S. 24th Street.