The other night I re-watched Marshall Corry’s 2005 documentary, Street Fight, about the 2002 Mayoral race in Newark, New Jersey, that pitted Cory Booker versus Sharpe James. I highly recommend this film: You will get the full measure of Cory Booker not only as an exceptional leader but as an individual accustomed to battling long odds.

The title of the documentary prompted this article. There are other street fights underway in the United States between major forces: small business versus big box, owner-occupants versus absentee landlords and quality versus parasitic capital.

Keep track of development in PhillyDo Something

Shift Capital is a social impact real estate firm that has been buying up former industrial spaces in the community and remaking them as outposts for maker firms and creative entrepreneurs.

They are now seeking to purchase a substantial portion of the Kensington commercial corridor and test the proposition of a neighborhood trust, to ensure that value appreciation can be captured and deployed by a community, in the service of the community.

Major market forces and large sources of private capital are undermining the fabric of thousands of city neighborhoods.

The work of Shift Capital is pathbreaking, imaginative and inspiring. It is also uncovering a story that is barely covered by national or local media. Major market forces and large sources of private capital are undermining the fabric of thousands of city neighborhoods. This street fight is being waged on multiple fronts.

Big box versus small business

The Kensington Corridor is a proxy for once thriving commercial corridors throughout the United States. It is a walkable corridor located under an elevated train with historic properties that still sport small businesses trying to survive.

Yet the major commercial action is several blocks away, along Aramingo Avenue, a corridor defined by big box retail, large parking lots and no soul. These big box thoroughfares exist all over the country, enabled by public policy changes, large and small, going back decades. Can Kensington Corridor revive? Can we rewind the economy? Shift Capital and organizations like Streetlight Ventures believe so if we can identify authentic businesses that meet local and larger demand and support them with finance, operations and marketing.

Owner occupants versus absentee landlords

The run up to the 2008 housing crisis was driven by shoddy underwriting and fraudulent activity. A different phenomenon has been taking place since then. Investors, large and small have been buying up “distressed properties,” creating a “slumlord economy.”

Brian Murray, the CEO of Shift Capital, explained the challenge well in a recent LinkedIn piece: “Absentee landlords—outside investors with no interest in the community other than their own short-term gain—are able to hide behind partnership structures that mask their identities, leaving tenants with few ways to speak up or fight back.”

Fortunately, this phenomenon is beginning to get mainstream attention, as in this recent article by Alana Semuels.

Quality versus parasitic capital

Opportunity Zones was described as a solution to communities that were disinvested and had not received market capital for decades. The reality of big box and investor owners show that these communities, by contrast, have been the recipients of large volumes of private investment, albeit the wrong kind.

About Shift Capital’s impactLearn More

As Murray explains: “In neighborhoods where the average home value is $50,000 (as in North Philadelphia or Baltimore), investors and developers find it nearly impossible to secure a loan big enough to cover a quality renovation. Rather, the current financing system requires developers to come out-of-pocket more than they would in wealthier neighborhoods—a risk few are inclined to take.”

How do we win the Street Fight?

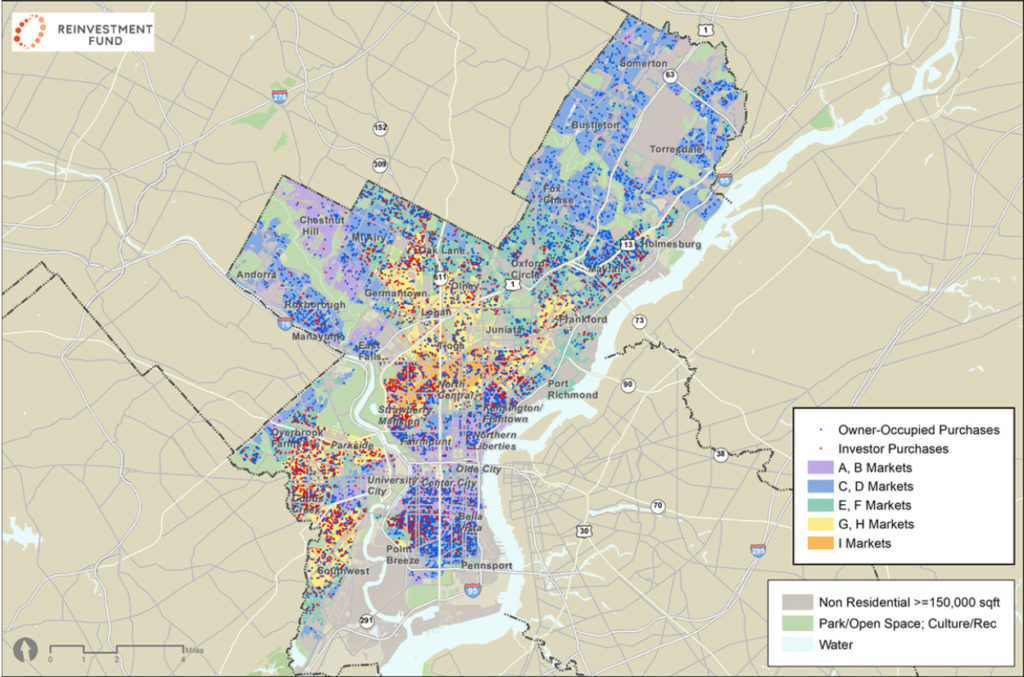

First, let’s unveil the challenge. Ira Goldstein of The Reinvestment Fund has been painstakingly conducting Market Value Analyses for a growing number of cities. These analyses show the variance of market strength across different typologies of city neighborhoods and particularly whether home purchases are being made by investors or by owners.

“Absentee landlords are able to hide behind partnership structures that mask their identities, leaving tenants with few ways to speak up or fight back,” Murray says.

The Philadelphia map below shows the method. In general, the purple markets are very strong, high-priced markets which are typically more renter-occupied than owner-occupied; blue (very solid and highly owner-occupied); green (classic middle markets) and yellow/orange (markets with stressors—e.g., foreclosures, vacancies, lower prices, little permitting or new construction).

Sales between 2016 and 2018 are represented by dots; red for investors and blue for owners. As you will see, the yellow and orange areas in West and Southwest Philadelphia, in addition to the area where Shift Capital is working, have lots of investor purchases.

Second, let’s solve for specific problems. There are already tools in the tool box. Cities should use their foreclosure powers to acquire tax delinquent properties more aggressively, which will establish the foundation for public asset ownership and creative disposition strategies.

Cities like Tulsa, Oklahoma, are already using their zoning powers to exclude the lowest rung of big box retail, creating space for local businesses.

Philanthropies and governments should solve for the quality capital challenge by providing guarantees to traditional banks to lend on smaller deals. (I could list potential federal reforms, but I will leave that for another day). The list goes on and on and on. There are tools that already exist which need to be applied at scale.

Finally, let’s test new mechanisms that build community wealth and organize new networks that advocate for them.

Articles by Bruce KatzRead More

At the same time, new networks of quality investors, entrepreneurs, developers, professionals, community organizations and churches can be formed to make these and other models the norm rather than the exception.

The United States faces a street fight of monumental proportions. It is winnable only if we recognize and root out its enabling features and combat it with real, financeable alternatives.

Bruce Katz is the director of the new Nowak Metro Finance Lab at Drexel University, created to help cities design new institutions and mechanisms that harness public, private and civic capital for transformative investment.

Photo courtesy chrisinphilly5448 / Flickr