Sharif El-Mekki is crying.

“I’m sorry,” he says, wiping the tears from under his eyes. But there’s no reason to apologize.

Sitting in Uncle Bobbie’s Coffee and Books, just blocks from the school he attended as a kid, the former teacher-turned-principal is getting choked up talking about how much he misses working in a school environment every day, as he did for the last 26 years, until just this past summer.

“I always thought of being an educator as an absolute honor. People trusted me with their children,” he says. “That’s a sacred bond that gave me a deep sense of purpose.”

Since May, El-Mekki has been channeling that sense of purpose and joy into his latest endeavor: The Center for Black Educator Development. The initiative has a three-pronged mission: to recruit Black teachers; to train Black teachers; and to retain Black teachers. It comes at a time in our city when, in a district whose student body is 49 percent Black, only 24 percent of teachers are Black, and less than five percent are Black males. (Nationally, a mere two percent of teachers are Black men.)

That lack of representation is a significant reason why Black students often struggle in school. It’s a finding that’s been emphasized in studies showing that, as The Baltimore Sun reported last November, “Black students who have one Black teacher by third grade are 13 percent more likely to enroll in college—and those who have two are 32 percent more likely.”

“Recent research has called attention to how an increased presence of African-American teachers can have positive impacts within K-12 educational spaces,” explains Christopher G. Wright, an assistant professor of Teaching, Learning, and Curriculum at Drexel University’s School of Education. “Beyond serving as role models and mentors for African American students, African-American teacher representation has been found to increase the likelihood of African-American students going to college and being labeled as gifted. These studies speak to the ways in which African-American teachers have conceptualized these issues through a lens of an ‘opportunity gap,’ where students have access to higher expectations and acknowledgment of the intellectual resources they come to school with.”

“I always thought of being an educator as an absolute honor. People trusted me with their children,” El-Mekki says. “That’s a sacred bond that gave me a deep sense of purpose.”

We need Black role models, El-Mekki explains, at a time when our country continues to tell Black children that they are worth less, and worthless.

El-Mekki, an occasional Citizen contributor, knows the power of strong role models: He grew up surrounded by them. There were his parents, both activists in the Black Panther Party, and his teachers, like Baba Changa at the Nidhamu Sasa African Freedom School he attended as a child.

“Baba Changa was my martial arts teacher and my geography and history teacher, and he had a huge influence on me. Right up until his death just a few years ago, I loved him like a father, and he inspired all of my classmates,” El-Mekki says. He’s still in touch with those classmates, who’ve gone on to become doctors, surgeons, professors. “Something happened in that school for that to occur,” El-Mekki notes.

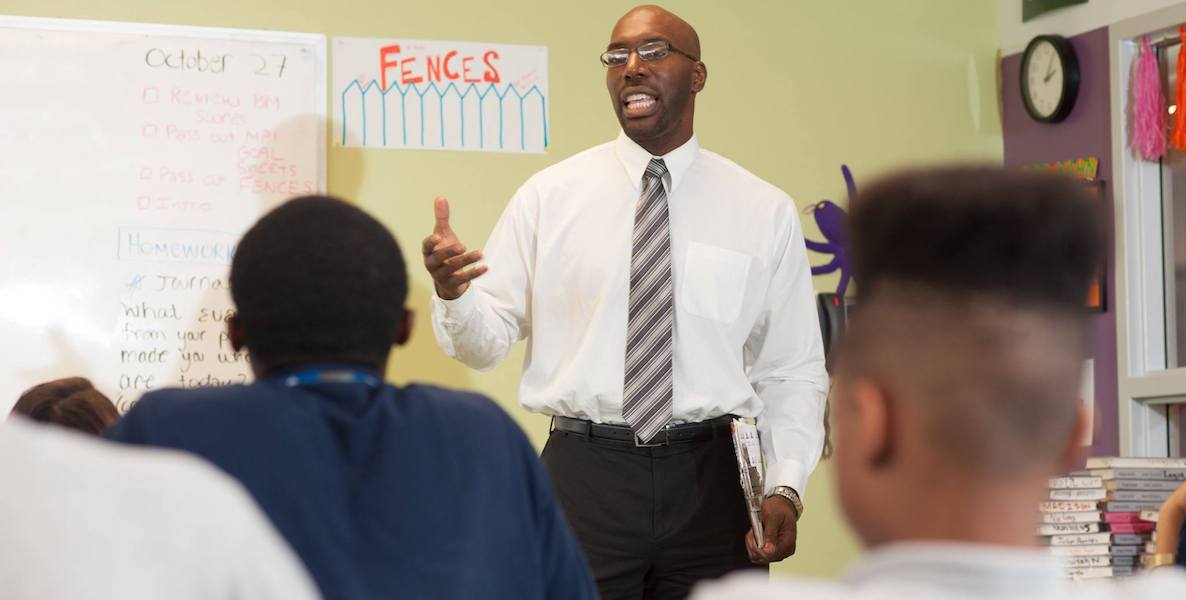

![]() It’s that “something”—that sense that you can be anything and change other’s lives—that El-Mekki has always been determined to share, first as a teacher and then assistant principal at John P. Turner Middle School; then as principal at Anna H. Shaw Middle School for five years; and as principal at Mastery Charter School-Shoemaker Campus for more than a decade. He brought that same mission to the creation, in 2014, of the Fellowship for Black Male Educators, a group designed to support and advance the careers of Black men who choose to teach.

It’s that “something”—that sense that you can be anything and change other’s lives—that El-Mekki has always been determined to share, first as a teacher and then assistant principal at John P. Turner Middle School; then as principal at Anna H. Shaw Middle School for five years; and as principal at Mastery Charter School-Shoemaker Campus for more than a decade. He brought that same mission to the creation, in 2014, of the Fellowship for Black Male Educators, a group designed to support and advance the careers of Black men who choose to teach.

And now he’s bringing that passion to the Center. After years of advocating for the district to hire more more black teachers, and working part-time to recruit and support them, El-Mekki decided it was time to do himself what he’d been urging others to do—to jump in where he saw a need, and fill it. It’s something, El-Mekki says, that schools Superintendent William Hite, a longtime supporter of his work, encouraged. “He’s the one who said, ‘You need to formalize this, people are asking for help, the district can’t do everything. We need partners—become one of our partners,’” El-Mekki says.

The gist of the Center’s programming is this: Open high school students’ eyes to the prospect of pursuing a career in teaching; give them opportunities to try teaching while in high school; provide support for them to take college-level classes in education, while still in high school, to offset some of the financial burden of college; give them teaching residencies while in college, to help thoroughly prepare them for the real world; nurture them with professional development and coaching once they’re hired, and for years to come—as a way to combat the fact that, nationally, nearly 50 percent of teachers leave the profession within the first five years, and in large urban districts like Philadelphia, that figure is closer to three years.

We need Black role models, El-Mekki explains, at a time when our country continues to tell Black children that they are worth less, and worthless.

Since its launch in May, the Center has raised more than $900,000, including a $300,000 donation from Sixers forward Tobias Harris, who presented El-Mekki with the award at an October draft-style ceremony, to the squealing delight of the many students who attended the event. Harris continues to be a strong advocate for El-Mekki’s work, and just last week surprised a group of educators of color at Bethune Elementary School, saying “The numbers don’t lie…that a young Black male that has an African-American teacher is 40 percent less likely to drop out of high school.”

![]() Funding goes toward programming, including the Center’s signature six-week Freedom Schools, which give high school students the opportunity to teach younger students; last summer, the Center hosted two Freedom Schools, and in 2020 it hopes to expand to four. Freedom Schools grew out of the Civil Rights movements; they offered an alternative to traditional public school and were committed, among other strong educational values, to instilling pride in African-American culture and history.

Funding goes toward programming, including the Center’s signature six-week Freedom Schools, which give high school students the opportunity to teach younger students; last summer, the Center hosted two Freedom Schools, and in 2020 it hopes to expand to four. Freedom Schools grew out of the Civil Rights movements; they offered an alternative to traditional public school and were committed, among other strong educational values, to instilling pride in African-American culture and history.

The Center also provides opportunities for high school students who aspire to teach to spend two weeks learning and doing team-building activities at Cheney University of Pennsylvania, and leads educational trips for students within the city and to destinations like Selma, Alabama. And it offers free professional development opportunities to current Philly teachers, like hands-on coaching about crucial skills such as lesson-planning.

“We can’t call ourselves a world-class city if we have this many students who are struggling in schools,” El-Mekki notes. “And we can’t be a city of adults. We have to be a city of our citizens, which includes the children who live in this city.”

Looking ahead, El-Mekki dreams of partnering with a museum to launch an exhibit along the lines of a Hall of Fame of Black Teachers. “Teachers shape society, and we have to recognize that,” he says, pointing out how few people realize that Ida B. Wells-Barnett and Mary McLeod Bethune, for example, were teachers. “We have to uplift the profession in different ways,” El-Mekki says.

And then there is the policy work. El-Mekki has been bolstered by state support like the Aspiring to Educate program, dubbed A2E, which covers the cost for high schoolers in Pennsylvania to take college-level teaching courses while in high school. Nearly 20 high school juniors from El-Mekki’s beloved Master-Shoemaker are already taking courses at Arcadia University, thanks to fiscal sponsorship from PA State Senator Vincent J. Hughes; and on December 20, the State granted The Center another $162,000 (from A2E’s total $4 million budget), which will allow 20 high school seniors to take courses through Temple. El-Mekki hopes to work with the city and at the federal level on similar programming.

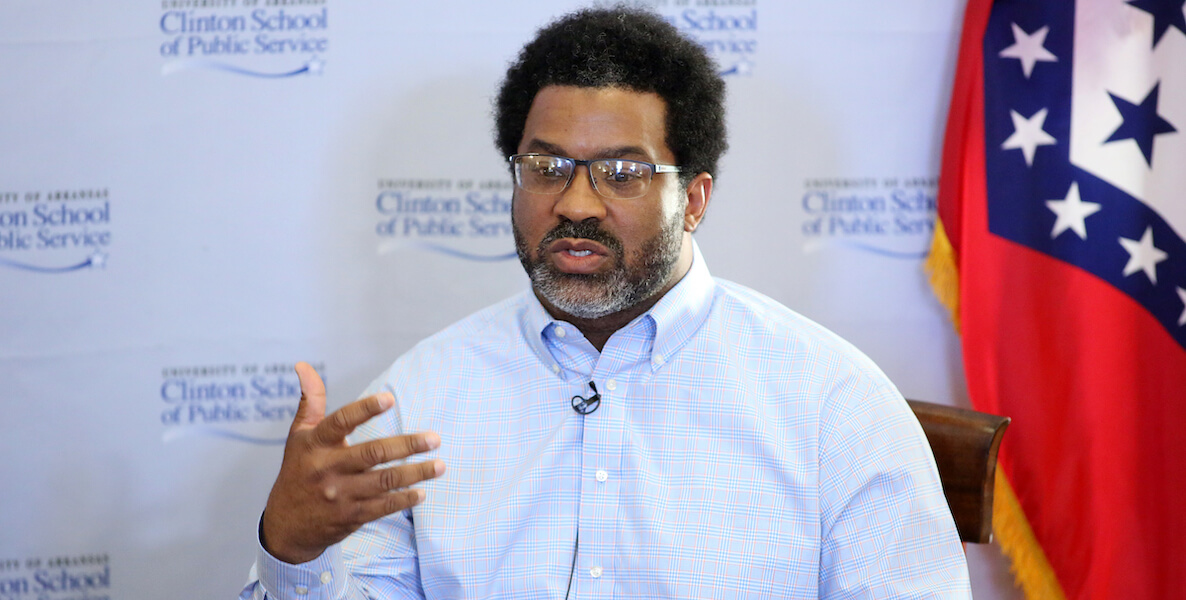

![]() For all the hand-wringing over the lack of existing role models, and how that affects current students, El-Mekki is inspired by what he’s seen coming down the line. “Things may look bleak, but help is on the way,” he says, recalling how impressed he was at a recent dinner with some young aspiring educators. “I can name 10, 15, Black boys right now—young men like Imere Williams, who’s currently one of two student reps on the School Board—who say Oh I’m gonna be one of the best teachers this city ever had. For them to have such passion about very specific things, that really inspires me.”

For all the hand-wringing over the lack of existing role models, and how that affects current students, El-Mekki is inspired by what he’s seen coming down the line. “Things may look bleak, but help is on the way,” he says, recalling how impressed he was at a recent dinner with some young aspiring educators. “I can name 10, 15, Black boys right now—young men like Imere Williams, who’s currently one of two student reps on the School Board—who say Oh I’m gonna be one of the best teachers this city ever had. For them to have such passion about very specific things, that really inspires me.”

To be sure, El-Mekki’s work is not just a “Black issue,” or something that stands to benefit only children of color. A diverse workforce of smart teachers is good for all children, for all teachers—and for the city as a whole. “We can’t call ourselves a world-class city if we have this many students who are struggling in schools,” El-Mekki notes. “And we can’t be a city of adults. We have to be a city of our citizens, which includes the children who live in this city.”

Want more local schools coverage? Check out these related articles:

- Student benched from basketball because of her hijab is a freedom fighter for our times

- Why guns in schools makes kids less safe

- The co-founder of The Fellowship for Black Male Educators on how he became a teacher