Two would-be cooks frantically huck some parsley onto a plate of what appears to be hash. It’s a potato and ground beef concoction, but the color tones—yellow, brown—are a little earthy, and could use some zhuzhing up. Chef Hugo Campos, who runs the kitchen, is happy with the dish; it’s certainly a contender for champion in this impromptu Chopped-style end-of-class cookoff taking place in a women’s shelter in North Philadelphia, the kitchen of which these culinary students use for training and for which they are preparing a massive lunch.

But Campos is less interested in whether his students know how to cook—they’re about a quarter of the way into a 14-week program, so they should, by now—than he is in knowing whether they understand culinary composition. “So what kind of flavors are in this dish?” he asks the two students.

They seem confused, and he has to walk them through it a bit. He’s patient, but they’re starting to get on his nerves, until one of the two cooks—a tattooed guy, with ink reading “STRESS” going down his neck—lands on one. “Savory,” he says.

“There we go,” says Campos. “This dish is great, but anyone can cook. You’re supposed to be learning what goes into cooking here.”

“I’m tough on them because those are the interviews they’re going to go to. They’re going to get judged on how old they are, the color of their skin, whatever it is. They have to rise above that, and find a way to put on a good performance,” Campos says.

The students nod as Campos works out of his exasperation. They’re happy to hear they did something right, and just as happy when they end up getting an answer right. There’s a sense of urgency and gratification among the students in this class; they work quickly, with economical movements. Aside from the little Chopped contest, they are preparing a lunch of empanadas and chimichurri with refried beans and yellow rice for everyone in the building in North Philly, and the hour approaches.

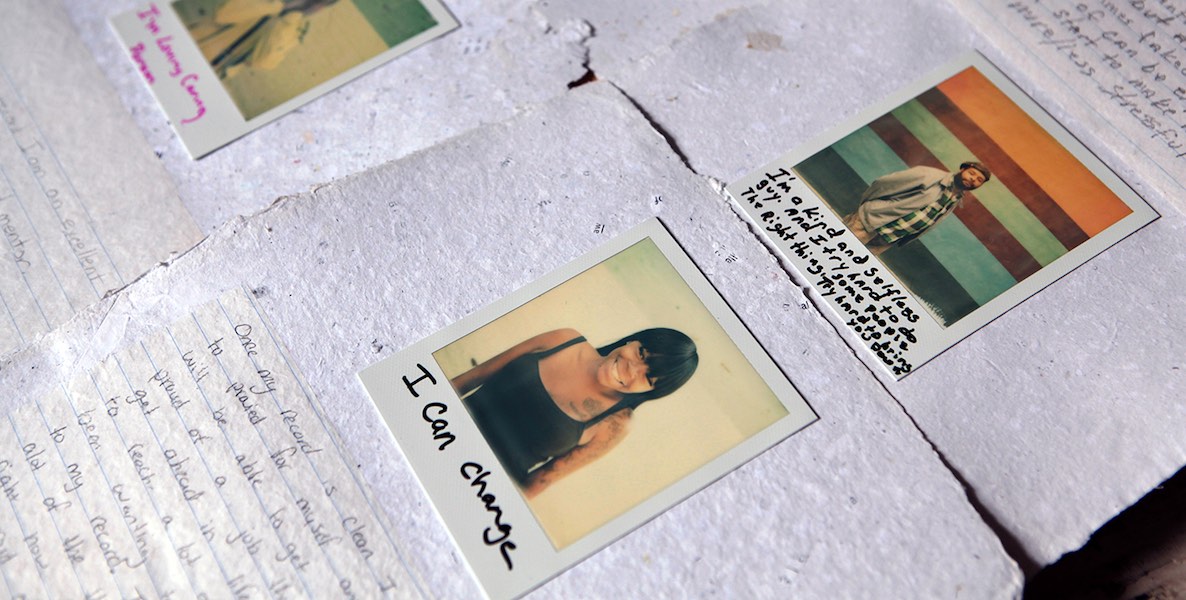

Campos attributes the willingness and excitement of his students to the fact that a lot of them have never really experienced an engaging learning environment. Many of them didn’t finish high school; most of them, by far, haven’t so much as sniffed a college class. This is, after all, a culinary and life skills class for current convicts and disadvantaged adults.

It’s called Philabundance Community Kitchen, and it’s been run by Philabundance since 2000, after the group received a $25,000 grant to help start an in-house culinary and work development program. Students face a massive wait list to get into the program and have to be referred. And why wouldn’t they be dying to get in? The folks at Philabundance characterize it as one of the most successful prison bridge and adult education programs around, with a success rate of 81 percent—meaning that 81 percent of students enrolled in the program find jobs in the culinary field after they graduate. According to Philabundance, over 600 PCK graduates have entered the workforce.

And jobs for the recently incarcerated can make the difference between staying out of prison or returning. According to one study by the Rand Corporation, people who participate in an educational program while in prison are 43 percent less likely to reoffend once they’re out. And another study suggests that recidivism rates for those placed in jobs immediately after leaving prison is between 3.3 percent and 8 percent, compared to a national average of between 31 percent and 70 percent.

The PCK course is intensive: After kitchen lessons, the group has a kitchen safety skills class. They also take life skills and math lessons and are supervised by an in-house life coach, who helps students figure out their paths going forward; while enrolled in PCK, enrollees learn communication, personal development and goal-setting skills. The course is pitched by PCK as an internship, and an employment specialist on staff is constantly looking for internships for current PCK enrollees and jobs for students. Over the course of more than 15 years, PCK has developed relationships with chefs and restaurants across Philadelphia, and culinary professionals are occasionally invited to watch PCK enrollees work in the kitchen.

One student I talk to, Jeff, is kind of an outlier in the program. He’s in prison for the immensely white-collar crime of mortgage fraud. He’s a South Jersey guy, a former accountant who admits that prison was a challenge to adjust to. But he says that his enrollment in PCK has changed everything for him; it has given him something to look forward to once his year-long sentence is up—a completely new direction. He says he wants to work in the culinary field once he’s out.

“PCK is a goldmine because of the resources they allow me to have,” says Jeff, who doesn’t want to reveal his last name. “Coming from where I’m coming from, PCK is a bridge for me between my incarceration to getting a fresh start, basically. PCK is providing the tools for me to get there.”

Now, Jeff has no reason to be humble about this. He’s a certified public accountant and had been working in the field for more than a decade; he was working from Manhattan for a while before being sentenced. Jeff says that many PCK enrollees have taken life skills classes before joining the program, but none of what he learned there even comes close to the totality and overall usefulness of what he’s learned in PCK.

“Everybody in our class is extremely engaged, everybody is really positive, everybody is helping each other,” he says. “Not everybody has taken my pathway, but they were certainly looking for a little help, a little direction back to gainful employment, because life sometimes happens. ”

The success of PCK is in no small part due to the folks overseeing the program, such as Chef Campos. Campos made his own roundabout way to working as a chef, and has special affinity for the people he works with. He came to the U.S. from El Salvador as a child. Growing up in California, his family had its own share of troubles, including drug addiction and incarceration. He lived alone with his mother until he was 17, when he was kicked out; his first jobs were in restaurant kitchens, and he became infatuated with the culture and speed of the work.

“It wasn’t really about the food, but I liked the atmosphere—I was that young kid who everyone told ‘pull up your pants, move your hat forward, stop cussing, don’t be a brat,’ that kind of stuff,” he says.

He received his associate’s degree in culinary arts in 2003 and worked as a restaurant chef for several years before becoming wearied by the industry. “It’s an industry that runs on Red Bull and cigarettes,” he says. “It’s just really easy to burn out.”

And so he got into teaching. Just not the Culinary Institute of America kind of teaching. Out in Seattle, he began working for a program that helped teach culinary skills to the homeless and disadvantaged; liking the work, and looking to step up the challenge, he applied to PCK, which he joined as head chef in 2015. Campos realizes that what a lot of the folks in the program need is a sense of direction, one that can only be provided with in-your-face instruction and some serious tough love. Campos references the moment at the shelter earlier, when he was coming down hard on his students for not being able to figure out what flavors were in the dish they prepared.

PCK has a success rate of 81 percent—meaning that 81 percent of students enrolled in the program find jobs in the culinary field after they graduate. According to Philabundance, over 600 PCK graduates have entered the workforce. And jobs for the recently incarcerated can make the difference between staying out of prison or returning.

“The conversation was not necessarily about cooking,” he says. “It’s more about your presentation at the end of the day. What you put in front of somebody, how you speak, your thought process—it’s being judged. You’re on stage, whether you know it or not. I’m tough on them because those are the interviews they’re going to go to. They’re going to get judged on how old they are, the color of their skin, whatever it is. They have to rise above that, and find a way to put on a good performance.”

Each cycle of the program lasts for 14 weeks, and students must be prepared for midterm and final exams. Campos teaches them everything from dicing to dish washing to food safety, and occasionally brings in a guest chef. Under his leadership, he envisions more for the program—particularly a catering service, so that the students can have an actual job in food services on their resume once they get out.

But for now, he’s content with the success stories he can help facilitate. “We have a lot of graduates from this program who are executive chefs, who work in really nice restaurants,” Campos says. “Stephen Starr restaurants, they’re out there. And they all started here.”

If the empanadas and chimichurri are any indication of their skills at all, I implore any restaurant looking for new talent: Hire these people immediately.

Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated the number of people who PCK graduates who have found culinary jobs. It is 600.

Photos provided by Philabundance Community Kitchen