Malkia Singleton Ofori-Agyekum believes that the messenger makes a difference.

“You’re going to take what you hear from someone you don’t identify with versus a person you do identify with in a very different way,” she says.

Support ParentChild+Do Something

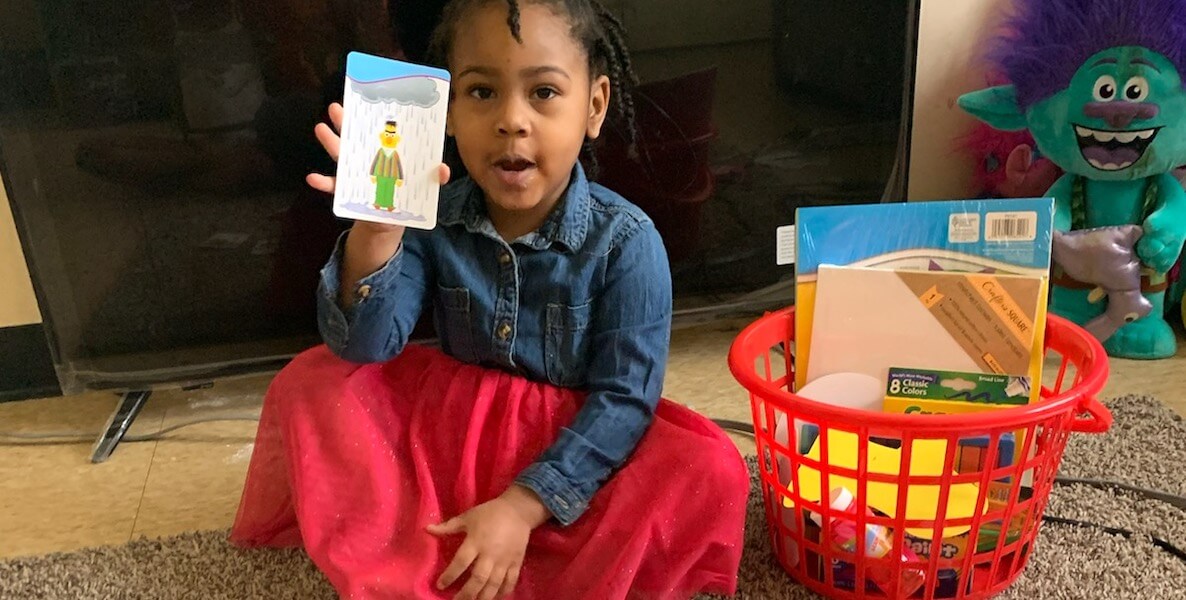

That cultural fit sets the stage for the success of the program, which targets low-income families with children between the ages of 16 months and four years. Over the course of twice-weekly home visits for two years, specialists bring books and toys that fuel early literacy, while modeling bonding skills for parents to emulate with their children.

The visits are a time for families to play and take a timeout from life’s stressors. But they’re deeper than that. “Not everyone knows the importance of playing with their child, or talking to their child or praising their child,” Singleton Ofori-Agyekum says. “To have someone come in and show you that in a nonjudgmental way creates new habits. This becomes the norm, and it’s transformative.”

It’s experiential learning on families’ home turf.

A more grassroots approach …

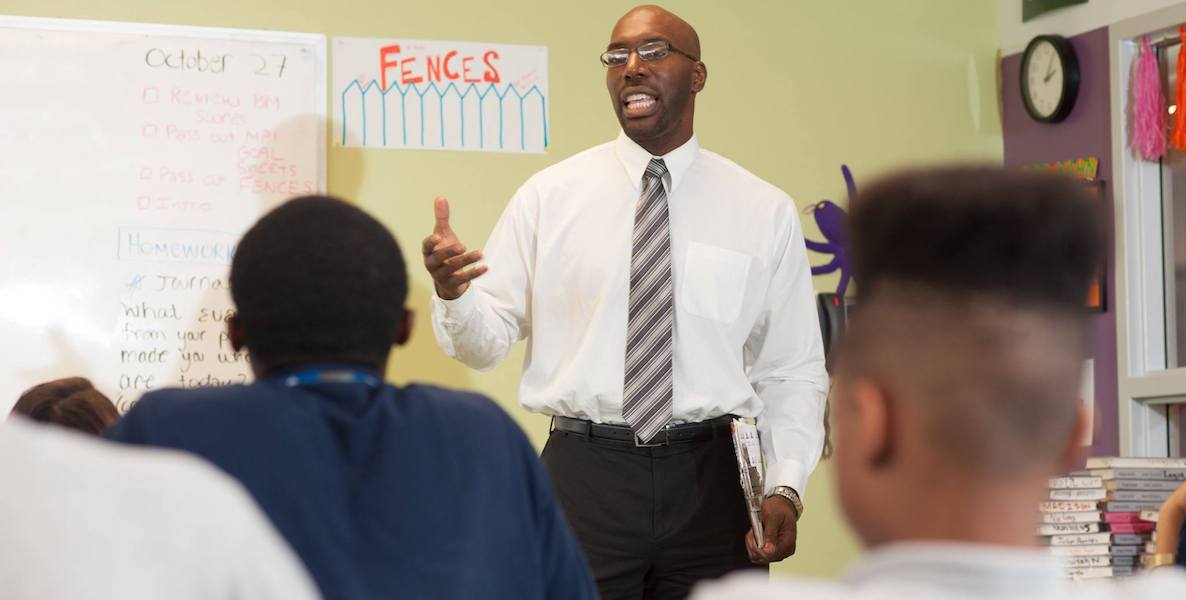

There are thousands of home-visiting programs in the United States, and while many employ nurses or social workers, ParentChild+ opts for a more grassroots approach.

Home visitors are community members who undergo 16 hours of training; many of them have gone through the program as parents themselves. Recruitment of families is predominantly by word of mouth, with staffers doing outreach at playgrounds and on the street, in addition to reaching out to daycare centers, pediatric practices and community programs.

The opportunity to work in her immediate community in North Philadelphia is what drew Anieka Mukhtar, a coordinator at ParentChild+, to the program when it launched in Philly in 2016.

When you look at a community that’s predominantly the same race, she says, you assume the culture’s the same—but it’s not. “Individual cultures exist from one cluster of households to the next. If I live the next block over from you, then we likely have more things in common than we would if we lived even 20 blocks apart,” says Mukhtar, who’d been working as a preschool teacher before joining ParenChild+.

“You’re going to take what you hear from someone you don’t identify with versus a person you do identify with in a very different way,” Singleton Ofori-Agyekum says.

Empathizing with families—shopping at the same supermarkets, using the same laundromats, understanding the experience of relying on food stamps or being a single parent—are the nuances that set ParentChild+’s team of home visiting specialists up for success. “Emotionally, we speak the same language,” Mukhtar says.

Linguistically, they do too: ParentChild+ works with native-born families but also with immigrant and refugee families who speak Spanish, French, Mandingo (or Mandinka), Swahili and other African dialects.

“To have someone speak your language when you’re not from here, you can’t put a price on the impact that makes,” Singleton Ofori-Agyekum says.

“You help them reawaken the skills they already have … ”

The roots of ParentChild+ go back to the 1960s, when psychologist and social worker Dr. Phyllis Levenstein was tasked with stanching the growing number of high school dropouts. Her approach: Reach parents and their kids at home, before they start school.

ParentChild+ during Covid-19Video

It also has deep troves of data, tracked through its national office in Mineola, NY, as well as on the local level, by Lehigh University. And that data consistently shows success: 84 percent of children who’ve gone through the program graduate from high school, compared to 72 percent in Philly overall. A longitudinal, randomized control group study of ParentChild+ found that low-income children who completed two years of the program went on to graduate from high school at the rate of middle class children nationally, 20 percent higher than their socio-economic peers and 30 percent higher than the control group in the community.

By third grade, participants are 50 percent less likely to be referred to special education compared to their peers who did not participate in ParentChild+; and their students measure 10 months ahead of their chronological age when they enter kindergarten in terms of national school-readiness standards, which look at areas like color and number concepts, knowledge of body parts, and other abilities related to academic success.

Of the many unfair stereotypes Mukhtar knows exist about the families she serves is that they’re content living in their situation. She knows that’s simply not true.

In Philly, with four coordinators overseeing 22 early learning specialists, ParentChild+ has served 248 families this year; their goal is to serve 400. Their current annual budget is $1.2 million—local support comes from organizations like Vanguard, GreenLight Fund, William Penn Foundation, The Philadelphia Foundation, West Philadelphia Promise Neighborhood at Drexel University, United Way of Greater Philadelphia and Southern New Jersey, and PHA—and, explains Katie Rubinstein, Director of Quality Initiatives for Public Health Management Corporation (through which ParentChild+ operates), they project that with another $400,000 annually, they could hire 16 more employees and reach their 400-family goal.

Working with more families wouldn’t just allow them to teach more children their ABCs—it would enable more families to find the skills they have, and the confidence to develop them.

Education solutionsRead More

Of the many unfair stereotypes Mukhtar knows exist about the families she serves is that they’re content living in their situation. She knows that’s simply not true.

“Whether it’s because of a vicious cycle of what their parents did based off of a lack of information, education and access, sometimes parents repeat that same cycle,” Mukhtar says. “They just need someone to come in and say you can do this. You have many options. Let me just show you a few of them. Sometimes, they just need to see a little bit of light.”

Rising to pandemic-era challenges

During Covid-19, ParentChild+ has risen to different challenges. Staffers have taken stock of families’ most basic needs, dropping off diapers and wipes, food and cleaning supplies. They’ve helped families get tablets and technology to continue meeting virtually. They suspected that some families might feel too overwhelmed to continue their sessions during the pandemic—but instead, 100 percent of participating families in Philly continued on.

This summer, a cohort of about 80 three-year-olds was scheduled to have graduation parties at playgrounds around Philadelphia, to celebrate their hard work, and that of their families. Instead, staff will be dropping off balloons and backpacks, each one containing a craft kit to make a picture frame in which to proudly display a photo from this alternative graduation day.

Khalesha McKie’s son is among this class of 2020. An employee and resident of PHA, McKie has had such a fulfilling experience in ParentChild+, that she’s sad to be moving on.

Over the course of the last two years, she has watched in awe as her son’s vocabulary and enunciation and love of reading and books grew. She also watched as her home specialist, Rochelle Hankerson, became like another grandmother to her son, another member of her family.

And she feels endlessly grateful to ParentChild+ for addressing her needs during the pandemic: Staffers provided her family with fresh fruits and vegetables and guidance to additional resources after McKie shared her feelings of heightened anxiety with Mukhtar.

“Our home visitors have been the trusted sources our families turn to when they need information and support,” says Singleton Ofori-Agyekum. “They felt safe enough to say I don’t have food, I don’t have diapers, and thankfully we were able to meet those needs.”

Header photo courtesy ParentChild+