If you’ve ever been to a major art museum, chances are you’ve been looking at work mostly made by men. That’s because there’s a significant disparity between the number of male and female work in most museum permanent collections, and also in what ends up on their walls.

The unequal art ratio is even greater for men to women of color. But a handful of museums are committed to changing that imbalance—and Philadelphia’s own Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts is leading the way.

According to a fascinating study published last month by In Other Words, a ![]() Sotheby’s editorial project with global art market newswire artnet News, in the last 10 years PAFA has been acquiring artwork by women at a rate five times faster than the national average of 11 percent. (The Philadelphia Museum of Art was not included in the study.)

Sotheby’s editorial project with global art market newswire artnet News, in the last 10 years PAFA has been acquiring artwork by women at a rate five times faster than the national average of 11 percent. (The Philadelphia Museum of Art was not included in the study.)

Coming in first of the 26 museums studied, 58 percent of PAFA’s new acquisitions were works by women. And according to a similar study conducted by In Other Words and artnet News in 2018, PAFA has acquired more work by African-American artists than almost any other museum in the last decade.

To compare, the study also calculated the following acquisition-of-female-art percentages for these museums: Museum of Fine Arts Boston at 4 percent; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art at 12 percent; Museum of Modern Art in New York at 23 percent; The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York at 40 percent; and Dia Art Foundation in New York at 57 percent.

What museums put into their permanent collection creates the canon of art that signals what a society values and what is most worthy of being preserved. It has also come to signal to some extent whom the museum is inviting to visit. When museums don’t reflect the wider communities they serve, they risk becoming irrelevant, dismissed as out of touch and not serving the broader interests of citizens who demand a variety of stories, ideas and opinions to be expressed.

“The payoff for equity is survival and relevance,” says Anderson. “We understand we are here to serve everybody in Philadelphia. If people give us the honor of half of their Saturday and they come through our doors and can’t see themselves reflected in the art, why would they ever want to come back?”

“Museums are a reflection of society in which they exist,” says Brooke Davis Anderson, director of PAFA since 2017. “American institutions have historically been dominated by white male voices with the majority of resources going to white male artists. The marketplace reflects this and therefore museums reflect this as well.”

In America, the art of white men has dominated the canon of art history because of greater opportunity and resources. They have traditionally received more museum and gallery exhibitions, so more of their pieces have been bought—and eventually donated to museums. They and their work are written about more in scholarly critiques; their work garners higher prices on the commercial art market, which affects future sales as well. And on and on …

As the In Other Words/artnet News study states:

There have been few advances made—even as museums signal publicly that they are embracing alternative histories and working to expand the canon. The number of works by women acquired did not increase over time. In fact, it peaked a decade ago.

These findings challenge one of the most compelling narratives to have emerged within the art world in recent years: that of progressive change, with once-marginalized artists being granted more equitable representation within art institutions. Our research shows that, at least when it comes to gender parity, this story is a myth.”

The study found that since 2008 the 26 museums examined added 260,470 works of art. Women created 29,247 of them. New York’s Museum of Modern Art recently remodeled and expanded to make room for more exhibit space with the intention of showcasing lesser-known artists, but even that will not necessarily mean more women: As a recent New Yorker article points out, works by women made up less than 10 percent of MOMA’s collection in 1972; as of last year, that number had grown “all the way” to 11 percent.

But there is good news to report: PAFA gets this.

PAFA’s path has been different than other institutions from its earliest days. Founded in 1805, it based itself on the European art academy model, but diverged significantly from the Europeans by inviting women to exhibit work, and by purchasing their works in the early 1800s. Women were enrolled as students by 1844 and employed as faculty well before they were allowed to vote.

More recently, PAFA ventured into pattern-breaking territory when it deaccessioned Edward Hopper’s East Wind Over Weehawken (1934) at Christie’s in 2013, realizing $40.5 million in the sale. The sale was controversial at the time, but institutional leadership—including then-director Harry Philbrick, who went on to found Philadelphia Contemporary—determined it was an opportunity to build the museum’s collection, especially around contemporary art.

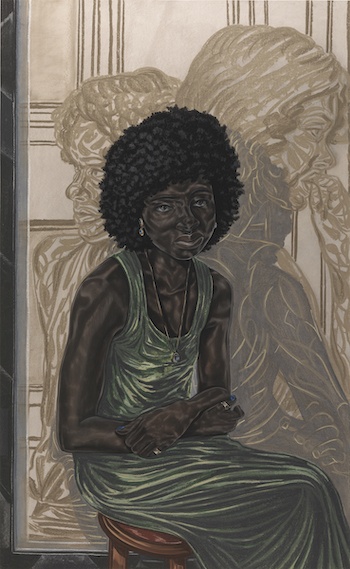

![]() The endowment from the sale yields approximately $2 million annually that goes to purchases of contemporary and historical art, in particular filling in gaps with women and artists of color.

The endowment from the sale yields approximately $2 million annually that goes to purchases of contemporary and historical art, in particular filling in gaps with women and artists of color.

In 2014, PAFA also hired a curator of contemporary art—Jodi Throckmorton—and expanded the collection’s committee of the Board of Trustees, adding new members with expertise in the field.

Now, PAFA states overtly its mission for new art: “The museum is especially interested in supporting women artists and artists often overlooked by the mainstream art world: artists of color, artists from regional, smaller art communities, and artists from the LGBT communities, with the belief that we can then tell a comprehensive and wholesome story about our cultural richness.”

Even before all this, PAFA received a significant boost that helped it move its collection in the right direction: In 2010, artist and philanthropist Linda Lee Alter gave the museum a significant gift that included 500 works of art by women. Former Philadelphia School Superintendent Constance E. Clayton gave PAFA 78 works this spring by both male and female artists, almost all African American.

Where PAFA still needs work, according to the In Other Words/artnet News study, is in its exhibition record. Over the past decade, just 9 percent of its shows featured work by women. Anderson is aware and conscious of making changes.

“These findings challenge one of the most compelling narratives to have emerged within the art world in recent years: that of progressive change, with once-marginalized artists being granted more equitable representation within art institutions. Our research shows that, at least when it comes to gender parity, this story is a myth,” the study says.

“We saw our exhibitions did not have the same leadership as our collection growth,” Anderson says. “That is something that will start to shift and change in the next several years.”

Look for the first major retrospective of feminist artist Joan Semmel known for her large-scale erotic nudes in 2021.

It’s easy to go down a rabbit hole of auction prices, percentages and statistics that reflect a lack of parity between the sexes in the art world. It’s clear that this disparity has an effect on our collective psyche. Messages seep in from everywhere to shape a communal narrative about where power lies. And messages of a different sort can be transformative and equalizing.

I distinctly remember leaving 2015’s Star Wars: The Force Awakens featuring Daisy Ridley as the fabulously capable, resourceful protagonist and being thrilled and surprised at the novelty of a female hero who carried the action and the entire Star Wars universe. ![]() She didn’t use her sexuality or damsel-in-distress tropes to manipulate her way to success. She was a straight-ahead hero. The point was: I noticed this was a rarity and I wished for more representation of women like this.

She didn’t use her sexuality or damsel-in-distress tropes to manipulate her way to success. She was a straight-ahead hero. The point was: I noticed this was a rarity and I wished for more representation of women like this.

I had a similar thrill at the Barnes Foundation’s 2018 exhibition of work by Berthe Morisot. I recall that as I walked through the rooms I had an uneasy feeling that I had not been taught the full story during my art history classes years ago. Had my professors not fully presented the scale and weight of Morisot’s influence? She was an essential founding member of the French Impressionists, yet somehow I knew a lot more about her male colleagues Renoir, Monet, Degas and Manet. I remember bumping into another female journalist at that exhibition, who also felt the same giddiness and revelation as we took in Morisot’s accomplishments and artistic genius.

Seeing a diversity of work in museums matters. Seeing aspects of yourself reflected in movie heroes or work esteemed enough to end up on the walls of a museum is validating and energizing. And broadening the scope of perspectives on view may just be the key to growing museum membership rolls and keeping visitors and donors coming through its doors.

![]() This was made abundantly clear last year, during a show by Swedish artist Hilma af Klint, at New York’s Guggenheim Museum. Though relatively unknown, the female artist’s show attracted the youngest audience of any Guggenheim exhibition, and brought in a 34 percent increase in membership. Those are the kinds of statistics museums crave.

This was made abundantly clear last year, during a show by Swedish artist Hilma af Klint, at New York’s Guggenheim Museum. Though relatively unknown, the female artist’s show attracted the youngest audience of any Guggenheim exhibition, and brought in a 34 percent increase in membership. Those are the kinds of statistics museums crave.

“The payoff for equity is survival and relevance,” says Anderson. “People should see themselves in the galleries. PAFA cares about art equity and telling a sweeping story of American art. We understand we are here to serve everybody in Philadelphia. If people give us the honor of half of their Saturday and they come through our doors and can’t see themselves reflected in the art, why would they ever want to come back? We want them to feel their American experience is reflected in what we choose to acquire and put on view.”

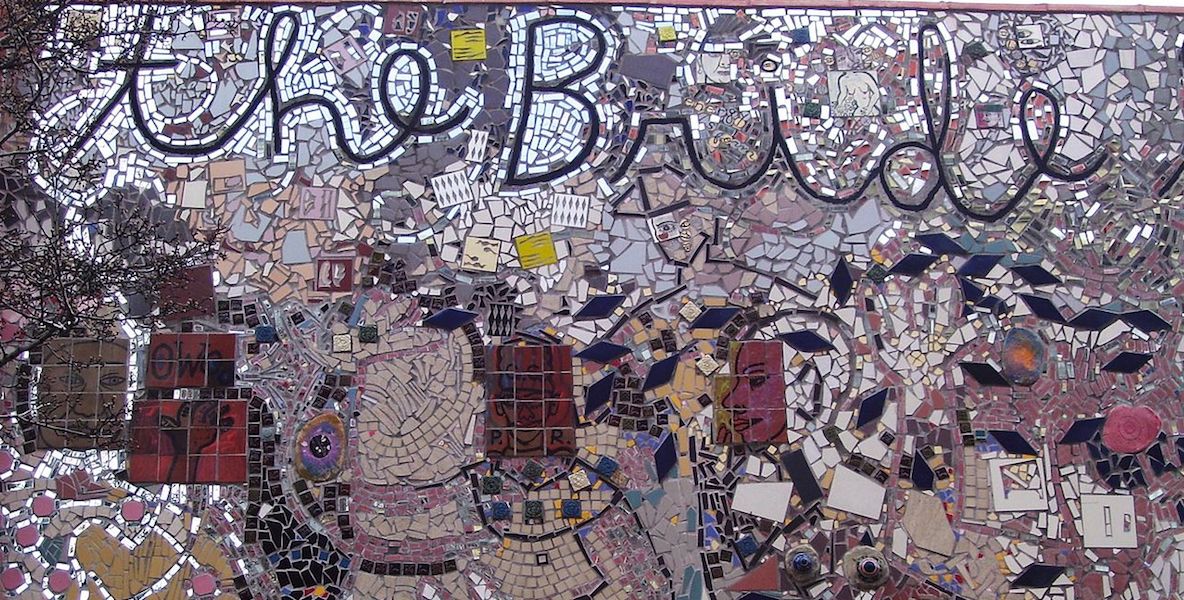

Photo courtesy B. Krist / Visit Philadelphia